It All Falls Down

A plummeting cougar population alters the ecosystem at Zion National Park

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/cougar_cougar.jpg)

Growing crowds at Utah's Zion National Park have led to the displacement of cougars, the area's top predator, resulting in a devastating series of changes to the region's biodiversity, environmental scientists report.

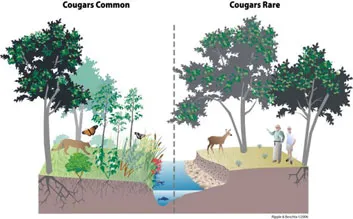

Compared with a nearby habitat in which cougars still thrive, Zion has fewer cottonwood trees, butterflies, amphibians and wetland plants, and much more deer, according to a paper that appears in the December Biological Conservation.

"The effects have been quite strong and rippled through this ecosystem," says Robert L. Beschta of Oregon State University, who coauthored the study.

Zion's dwindling cougar population traces its roots to the late 1920s, when park management made efforts to increase visitation. By 1934, tourism had risen considerably, attracting some 70,000 visitors a year—about eight times what it had been only a decade earlier. Today the park receives about three million annual visitors.

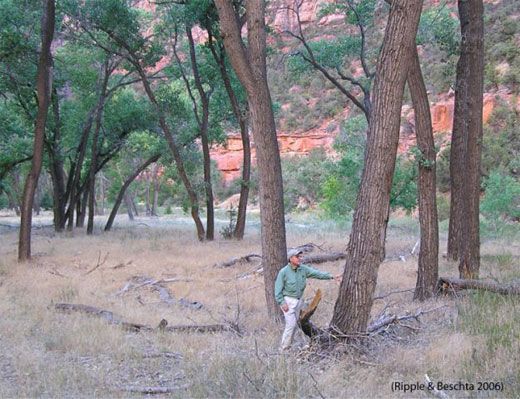

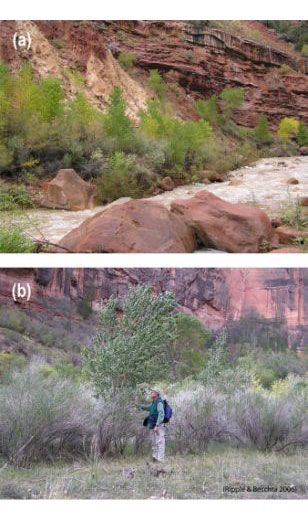

To measure the impact of the shrinking cougar population, Beschta and William J. Ripple, also of Oregon State, collected census data on Zion's deer populations dating back to the 1930s. They also studied tree rings to estimate the age and abundance of cottonwoods, a favorite food of young deer, and surveyed nearby river banks to gauge the number of butterflies, frogs, lizards and certain plants.

The researchers compared their figures with similar populations from an area next to Zion called North Creek, which has a stable cougar population. They found more deer, fewer young cottonwood trees and less riverbank life in Zion—a difference they attribute to the absence of cougars in the park.

"These major predators are a key component of maintaining biodiversity," Beschta says. "Most people look [around Zion] today and think it's natural, but it's not."

The evidence from Zion suggests a system of trophic cascading, in which a reduced population of top predators has a trickle-down affect on the plants and animals below them in the food chain.

In Zion's case, tourists caused the shy cougar, also called the mountain lion, to flee the area. Deer, which are the cougar's main prey, increased in abundance, leading to a spike in the consumption of young cottonwood trees. These changes contributed to the erosion of riverbanks and a decline in wetland species.

Though trophic cascades have been well-documented in marine life, environmental scientists have debated their presence on land, says biologist Robert T. Paine of the University of Washington, who was not part of the study. Some cascade doubters believe that competition for food regulates deer populations in the absence of a top predator.

"This is a terrific contribution to a growing body of evidence that [cascades] occur in major terrestrial systems," says Paine, who coined the term "trophic cascade" in 1980. Recent studies of shrinking numbers of wolves in Yellowstone National Park have shown similar effects on plant-life.

Restoring at least part of the cougar population could, over time, rebalance Zion's ecosystem. One way to boost the number of predators might be to limit vehicle access to the park, speculates Ripple. When the park implemented a bus system that reduced car traffic in 2000, he says, cougar sightings increased.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/eric-jaffe-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/eric-jaffe-240.jpg)