It’s a Green, Green, Green, Green World

NASA and NOAA release satellite images of Earth and all its vegetation

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20130628032016Yukon-NASA-NOAA-vegetation-index-web.jpg)

On December 7, 1972, the Apollo 17 crew members—commander Eugene Cernan, lunar module pilot Harrison “Jack” Schmitt and command module pilot Ron Evans—captured the full sphere of Earth, a first of its kind image, from about 28,000 miles into space. Al Reinert, a screenwriter for Apollo 13, reflected in a 2011 essay in the Atlantic on the photograph, called the Blue Marble, and just how privileged the astronauts’ view was that day:

“You can’t see the Earth as a globe unless you get at least twenty thousand miles away from it, and only 24 humans ever went that far out into space…. In order to see our planet as a fully illuminated globe you need to pass through a point between it and the sun, which is a narrower window than you might think if you’re traveling at 20,000 miles an hour.”

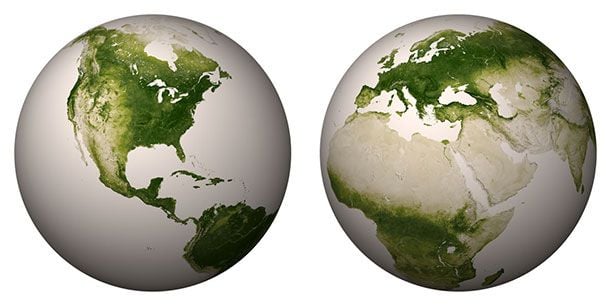

Thankfully, NASA has been sharing privileged views of the planet with the public for decades through various collections of satellite images. The latest set released by both NASA and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration last week takes a look not at the blue oceans that make up three-quarters of the Earth, but at the land and its varying degrees of vegetation.

For one year, from April 2012 to April 2013, the Visible Infrared Imaging Radiometer Suite (VIIRS) on the Suomi NPP satellite (the satellite also made these “Black Marble” images of the Earth at night possible) collected data on the visible and near-infrared light being reflecting into space. In a press release, NOAA explains how these levels of reflected light help determine the “vegetation index,” a measure of plant life in any given region when viewed from space:

“Plants absorb visible light to undergo photosynthesis, so when vegetation is lush, nearly all of the visible light is absorbed by the photosynthetic leaves, and much more near-infrared light is reflected back into space. However for deserts and regions with sparse vegetation, the amount of reflected visible and near-infrared light are both relatively high.”

From this data came images of the Earth pared down to varying shades of green. ”The darkest green areas are the lushest in vegetation, while the pale colors are sparse in vegetation cover either due to snow, drought, rock, or urban areas,” NOAA reports. The video, above, even shows the changes in vegetation over the course of the year and its four seasons.

Forecasters can gather information from the satellite images about impending droughts, forest fire threats, even potential malaria outbreaks. (“As vegetation grows in sub-Saharan Africa, so does the risk for malaria,” NOAA told New Scientist.) And, beyond that, they do what Blue Marble and other views of Earth from space do—inspire awe.

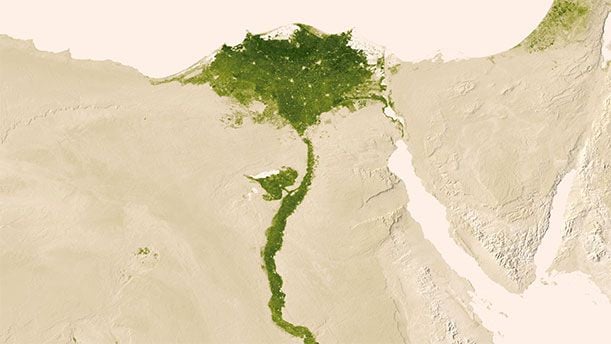

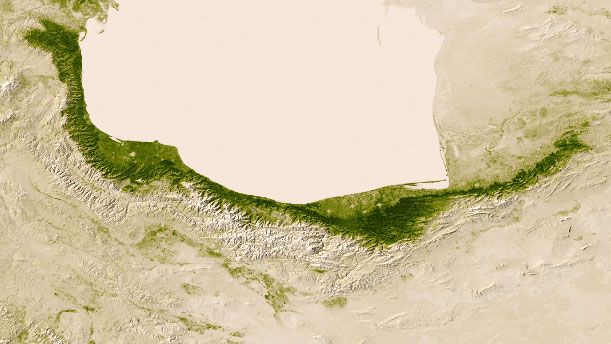

The more that I explore the satellite images, the more I lose my bearings within the physical geography. The images slip from the real world into the abstract, and the Nile River becomes just a winding stroke and the valleys of America’s Pacific Northwest, gnarled green textures—daubs and splotches of watercolor paint on parchment.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/megan.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/megan.png)