It’s a Myth: There’s No Evidence That Coffee Stunts Kids’ Growth

The long-held misconception can be traced to claims made in advertisements for Postum, an early 1900s coffee alternative

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/fb/f3/fbf31b6f-9a71-4a8e-b031-51ddefca3983/coffee.jpg)

Many parents, on special occasions, let their children drink Coke, Pepsi, or other sugary drinks. Most parents would never consider letting their kids drink coffee.

The reason why one caffeinated beverage is allowed, and the other forbidden? Because everyone knows, of course, that drinking coffee stunts the growth of children.

As much as we hate to give argumentative kids more ammo in undermining their parents, we love dispelling cherished scientific misconceptions. Despite decades of research into the effects of coffee drinking, there is absolutely no evidence that it stunts kids' growth.

"It's 'common knowledge,' so to speak—but a lot of common knowledge doesn't turn out to be true," says Mark Pendergrast, the author of Uncommon Grounds: The History of Coffee and How It Transformed Our World. "To my knowledge, no one has ever turned up evidence that drinking coffee has any effect on how much children grow."

That said, there isn't strong evidence that coffee doesn't stunt growth, simply because the long-term effects of coffee on children haven't been thoroughly studied (in part, presumably, because it'd be hard to find a parent willing to make his or her kid drink coffee daily for years at a time). There has, however, been research into the long-term effects of caffeine on children, and no damning evidence has turned up. One study followed 81 adolescents for a six-year period, and found no correlation between daily caffeine intake and bone growth or density.

Theoretically, the closest thing we do have to evidence that caffeine affects growth is a series of studies on adults, which show that increased consumption of caffeinated beverages lead to the body absorbing slightly less calcium, which is necessary for bone growth. However, the effect is negligible: The calcium in a mere tablespoon of milk, it's estimated, is enough to offset the caffeine in eight ounces of coffee. Official NIH recommendations state that, paired with a diet sufficient in calcium, moderate caffeine consumption has no negative effects on bone formation.

But if the whole coffee stunting growth idea isn't rooted in science, where did it come from? Shrewdly calculated advertising.

"From the very beginning of people drinking coffee, there have been concerns that it was bad for you, for one reason or another," Pendergrast says, noting that coffee was banned for health reasons as far back as the 1500s, in Mecca, and in 1675, by King Charles of England.

Modern concerns about coffee' health effects in the U.S. can be traced to C.W. Post, an 1800s-era food manufacturer most well known for pioneering the field of breakfast cereal. He also invented a grain-based breakfast beverage called Postum, advertised as a caffeine-free coffee alternative, that was popular through the 1960s (and is still in production).

"Postum made C.W. Post a fortune, and he became a millionaire from vilifying coffee, and saying how horrible it was for you," Pendergrast says. "The Postum advertisers had all kinds of pseudoscientific reasons that you should stay away from coffee." Among the "evil effects" of coffee for adults, according to Post: it depressed kidney and heart function, it was a "nerve poison," it caused nervousness and indigestion, it led to sallow skin.

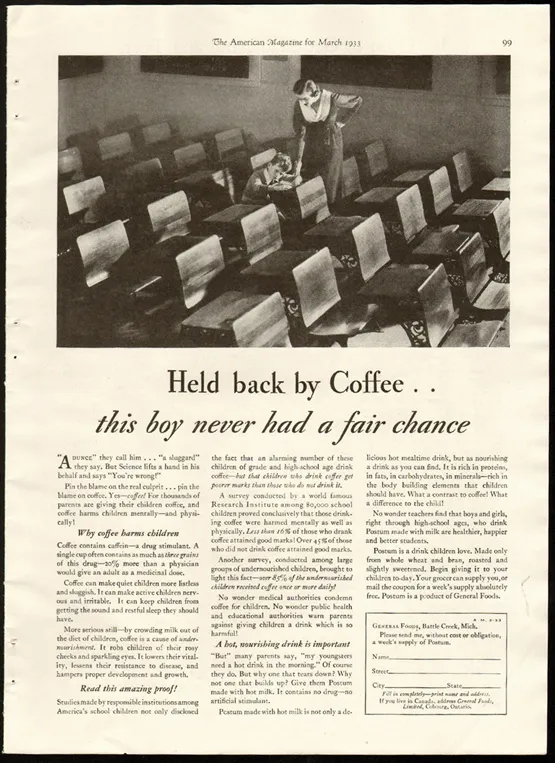

Even after Post died in 1914, his company's ads continued their attack on coffee, highlighting its effects on youth in particular and marketing Postum as a kid-friendly hot beverage. Postum's ads claimed that that coffee should never, under any circumstances, be served to children, for a number of reasons—it made them sluggish, irritable and sleepless, it robbed them of "rosy cheeks and sparkling eyes," it led to failing grades and, as the 1933 ad above claims, "it hampers proper development and growth."

Over time, it seems, the belief that coffee is unfit for children—and, specifically, that it stops them from growing—slipped into the country's cultural consciousness and took root, despite a total lack of scientific evidence.

Happily, Postum is now mostly forgotten, and coffee reigns. Virtually all of coffee's supposed ills have been debunked—including the idea that coffee stunts growth. On the whole, scientists now believe that the health benefits of drinking two to three cups of coffee per day (a reduced risk of developing dementia, diabetes and heart disease) outweigh the costs (a slight increase in cholesterol levels, for instance).

Of course, you might have your own very legitimate reasons for not letting kids drink coffee that have nothing to do with growth. A big concern is sleep, and how crucial it is for developing children—they need more of it than adults, and there's evidence that sleep disturbances could be linked with childhood obesity—so the fact that coffee packs more caffeine than tea or soda is an issue.

Then there are the more prosaic problems that could result from giving kids coffee. "My biggest concern is that caffeine is addictive," Pendergrast says. "And there is a lot of evidence that if you're addicted, and you don't get your caffeine, you suffer quite exquisite headaches, among other symptoms."

The only thing worse than a caffeinated child? An addicted yet caffeine-deprived child, suffering from a splitting headache, clamoring for a much-needed cup.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/joseph-stromberg-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/joseph-stromberg-240.jpg)