Jack Andraka, the Teen Prodigy of Pancreatic Cancer

A high school sophomore won the youth achievement Smithsonian American Ingenuity Award for inventing a new method to detect a lethal cancer

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Ingenuity-Awards-Jack-Andraka-631.jpg)

It’s first period digital arts class, and the assignment is to make Photoshop monsters. Sophomore Jack Andraka considers crossing a velociraptor with a Brazilian wandering spider, while another boy grafts butterfly wings onto a rhinoceros. Meanwhile, the teacher lectures on the deranged genius of Doctor Moreau and Frankenstein, “a man who created something he didn’t take responsibility for.”

“You don’t have to do this, Jack!” somebody in back shouts.

The silver glint of a retainer: Andraka grins. Since he won the $75,000 grand prize at this past spring’s Intel International Science and Engineering Fair, one of the few freshman ever to do so, he’s become a North County High School celebrity to rival any soccer star or homecoming queen. A series of jokes ensue about Andraka’s mad scientist doings in the school’s imaginary “dungeon” laboratory. In reality, Andraka created his potentially revolutionary pancreatic cancer detection tool at nearby Johns Hopkins University, though he does sometimes tinker in a small basement lab at the family’s house in leafy Crownsville, Maryland, where a homemade particle accelerator crowds the foosball table.

This 15-year-old “Edison of our times,” as Andraka’s Hopkins mentor has called him, wears red Nikes carefully coordinated with his Intel T-shirt. His shaggy haircut is somewhere between Beatles and Bieber. At school one day, he cites papers from leading scientific publications, including Science, Nature and the Journal of Clinical Neurology. And that’s just in English class. In chemistry, he tells the teacher that he will make up a missed lab at home, where of course he has plenty of nitric acid to work with. In calculus, he does not join the other students who cluster around a blackboard equation like hungry young lions at a kill. “That’s so trivial,” he says, and plops down at a desk to catch up on assigned chapters from Brave New World instead. Nobody stops him, perhaps because last year, when his biology teacher confiscated his clandestine reading material on carbon nanotubes, he was in the midst of the epiphany that scientists think has the potential to save lives.

After school Andraka’s mom, Jane, a hospital anesthetist, arrives in her battered red Ford Escort station wagon with a saving supply of chocolate milk. She soon learns that Jack’s big brother, Luke—a senior, and a previous finalist in the same elite science fair—has been ordered to bring his handmade arc furnace home. He built it in a school lab, but teachers grew nervous when he mentioned that the device could generate temperatures of several thousand degrees Fahrenheit, and melted a steel screw to prove it. The contraption will find a spot in the Andraka basement.

“I just say ‘Don’t burn down the house or kill yourself or your brother,’” the boys’ mother cheerfully explains. “I don’t know enough physics and math to know if that’s a death ray or not. I say use common sense, but I don’t know what they’re working on down there.”

***

Pancreatic cancer is one of the most lethal cancers, with a five-year survival rate of 6 percent. Some 40,000 people die of it each year. The diagnosis can be devastating because it is often delivered late, after the cancer has spread. Unlike the breast or colon, the pancreas is nestled deep in the body cavity and difficult to image, and there is no telltale early symptom or lump. “By the time you bring this to a physician, it’s too late,” says Anirban Maitra, a Johns Hopkins pathologist and pancreatic cancer researcher who is Andraka’s mentor. “The drugs we have aren’t good for this disease.”

But as the cancer takes hold, the body does issue an unmistakable distress signal: an overabundance of a protein called mesothelin. The problem is that scientists haven’t yet developed a surefire way to look for this red flag in the course of a standard physical. “The first point of entry would have to be a cheap blood test done with a simple prick,” Maitra says.

That’s exactly what Andraka may have invented: A small dipstick probe that uses just a sixth of a drop of blood appears to be much more accurate than existing approaches and takes five minutes to complete. It’s still preliminary, but drug companies are interested, and word is spreading. “I’ve gotten these Facebook messages asking, ‘Can I have the test?’” Andraka says. “I am heartbroken to say no.”

***

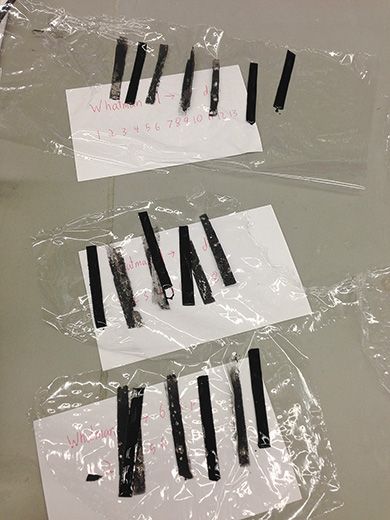

That fateful day in freshman biology class last year, Andraka had a lot on his mind. A close friend of his family had recently died of pancreatic cancer, and Andraka had been reading about the disease. At the same time, he and his father, Steve, a civil engineer, had been using carbon nanotubes to screen compounds in water from the Chesapeake Bay. Andraka had frankly become a little obsessed with the nanotubes, which look to the naked eye like little piles of black dust, but are really tiny cylinders about 1/50,000 the diameter of a human hair that can form microscopic networks. “They have these amazing properties,” Andraka explains. “They are stronger than steel. They conduct electricity better than copper.”

The Science paper he was covertly reading at his desk was about applications for nanotubes. With half an ear, Andraka listened to his biology teacher lecture on antibodies, which bind to particular proteins in the blood. Suddenly, the two ideas collided in his mind. What if he could lace a nanotube network with mesothelin-specific antibodies, then introduce a drop of a pancreatic cancer patient’s blood? The antibodies would bind to the mesothelin and enlarge. These beefed-up molecules would spread the nanotubes farther apart, changing the electrical properties of the network: The more mesothelin present, the more antibodies would bind and grow big, and the weaker the electrical signal would become. Other scientists had recently designed similar tests for breast and prostate cancers, but nobody had addressed pancreatic cancer. “It’s called connecting the dots,” Maitra says.

Andraka wrote up an experimental protocol and e-mailed it to 200 researchers. Only Maitra responded. “It was a very unusual e-mail,” he remembers. “I often don’t get e-mails like this from postdoctoral fellows, let alone high-school freshmen.” He decided to invite Andraka to his lab. To oversee the project, he appointed a gentle postdoctoral chemist, who took the baby-sitting assignment in stride. They expected to see Andraka for perhaps a few weeks over the summer.

Instead, the young scientist worked for seven months, every day after school and often on Saturdays until after midnight, subsisting on hard-boiled eggs and Twix as his mother dozed in the car in a nearby parking garage. He labored through Thanksgiving and Christmas. He spent his 15th birthday in the lab.

Not having finished even freshman biology, he had a lot to learn. He called forceps “tweezers.” He had a nasty run-in with the centrifuge machine, in which a month’s worth of cell culture samples exploded, and Andraka burst into tears.

But sometimes his lack of training yielded elegant solutions. For his test strips, he decided to use simple filter paper, which is absorbent enough to soak up the necessary solution of carbon nanotubes and mesothelin antibodies, and inexpensive. To measure the electrical change in a sample, he bought a $50 ohmmeter at Home Depot. He and his dad built the Plexiglas testing apparatus used to hold the strips as he reads the current. He swiped a pair of his mom’s sewing needles to use as electrodes.

About 2:30 a.m. one December Sunday, Jane Andraka was jolted from her parking lot stupor by an ecstatic Jack. “He opens the door,” she remembers, “and you know how your kid has this giant smile, and that shine in their eye when something went right?” The test had detected mesothelin in artificial samples. A few weeks later, it pinpointed mesothelin in the blood of mice bearing human pancreatic tumors.

***

Andraka’s appetite for science and success knows no bounds: His euphoric reaction to the Intel win quickly went viral on YouTube. In the months since that triumph, reality has sunk in a little as he spoke with attorneys and licensing companies. “I just finished the patent,” he says, “and I’m going to start an LLC soon.” But Maitra—who believes that the dipstick should ultimately be modified to identify other flag-raising cancer proteins along with mesothelin—has made clear that Andraka has a lot more testing to do before publishing a peer-reviewed paper on the work, the next step. Even if all goes well, the product probably wouldn’t be marketed for a decade or so, which, to a teenager, is practically eternity.

And of course, he’s got to start working on next year’s science fair project. He has no shortage of ideas.

“He’s ahead of his time in many ways,” Maitra says. “Taking one idea and seeing how to extrapolate something even more expansive, that’s the difference between being great and being a genius. And who comes up with ideas like this at 14? It’s crazy.” Andraka is young enough to speak with perfect earnestness about “when I grow up.”

Even so, he is in high demand, giving TED talks and speaking at international ideas festivals. His iPhone contains snapshots of dignitaries ranging from Bill Clinton to Will.i.am. In September, Andraka attended high school so infrequently that a few teachers thought he’d dropped out. “But I don’t want to quit high school,” he says. “High school is fun—sometimes.” Occasionally he wishes that he had more time for it, and kid stuff in general. He likes to watch “Glee” and to compete with Luke on the national junior whitewater rafting team.

Then there’s all that homework to catch up on. His English class is busy discussing Brave New World, about a technological dystopia where the inventor Henry Ford is worshiped as a god. “Your Fordliness,” the teacher explains, is the standard honorific.

“Your Jackliness,” one classmate whispers.