New Jane Goodall Documentary Is Most Intimate Portrait Yet, Says Jane Goodall

The famed chimp researcher didn’t want yet another documentary made about her. Jane changed her mind

Jane Goodall used to dream about being a man—literally.

“I suppose my mind turned me into a man in my dreams so I could have the sort of dreams that I subconsciously wanted,” she tells Smithsonian.com. “I could do more exciting things in my dreams if I was a man.” After all, the pioneering chimp researcher’s favorite childhood books were Dr. Doolittle and Tarzan, both of which featured daring and cunning men, with women playing the supportive role. “Tarzan's Jane was a wimpy pathetic little creature," she says. "I didn't want to be like that."

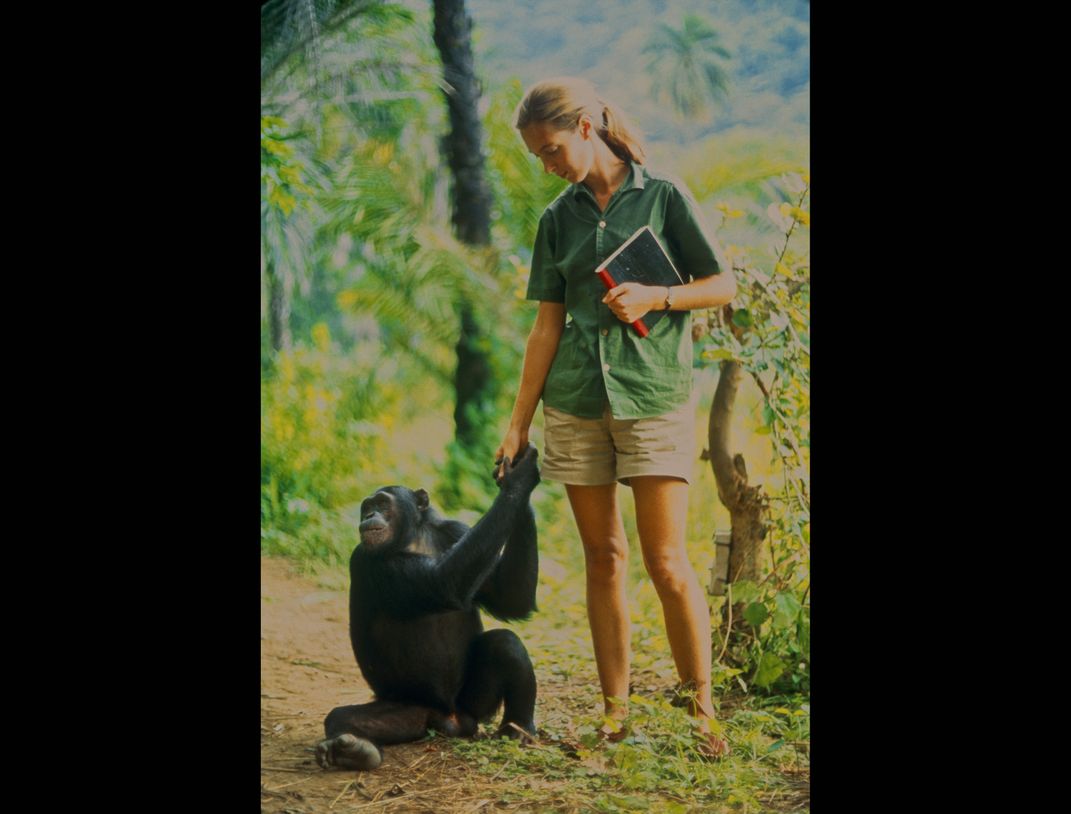

These are the kind of intimate details in store for viewers of Jane, a new documentary on Goodall composed of 140 hours of 16mm recordings that had been tucked away in the archives of National Geographic for over 50 years. Wildlife videographer Hugo van Lawick, who later became Goodall's husband, shot the footage in the early 1960s for a National Geographic documentary. But after it was spliced and diced, the remainder of the footage sat forgotten in the archives—until now.

Jane is directed by Brett Morgen, known for his biopics of cultural icons like The Rolling Stones and Kurt Cobain. When Morgen received the film in 2015, he was taken aback. "We thought we were going to get 140 hours of scenes," he tells Smithsonian.com. Instead, he had 140 hours of misordered shots. "It was as if someone took all of the letters ... that are used to [write] the book Watership Down ... put them on the floor and then said make the words," he explains. He and his team shut down production and began sorting through what he refers to as an "insane jigsaw puzzle."

But under his direction, the scenes slowly came to life.

By now most people know how Goodall’s hard-won discoveries about chimp intelligences reshaped our thinking about what we now know to be one of our closest evolutionary ancestors. But Jane, which hit select theatres in October, invites viewers on a more personal journey through the jungle—delving into the Goodall's first love, the birth of her son and the many challenges she faced as an ambitious woman in a male-dominated field. Many moments hint at genuine interactions: Goodall occasionally looks directly at the camera, perhaps flirting with Hugo, who sits behind the lens. In one scene, Hugo grooms Jane like a fellow chimp, and in another Jane sticks her tongue out at the camera (and Hugo).

Unlike past narratives, the film also takes a less fawning, and more down-to-earth tone toward Goodall’s accomplishments and life's work. "Because I wasn't a sycophant, I approach things perhaps as matter of factly as she did," says Morgan. "Now from where I sit today, I consider myself one of the world's greatest Jane Goodall fans, and am in completely in awe of her. But at the time, that wasn't where my head was at," he adds. Smithsonian.com interviewed the wildlife icon on her reactions to the film and how she navigated the many challenges in her career.

What was your reaction when you heard that National Geographic had found this footage and hoped to make a new documentary?

When somebody said that the Geographic wanted to make another film, I said, "not another one." Geographic [had already] went through all of Hugo's material and took out what they considered the best. But in the end, I was persuaded it would be a good idea.

What did you think about final result?

I think it's a very honest use of the footage. It showed things as they were without trying to cut it and smooth it.

It took me back to those early days in the way that no other documentary has. I just felt I was there in the forest. It's got more family life. It's got Grub (Goodall’s affectionate nickname for her son, Hugo Eric Louis) when he's a little gorgeous baby. I'd forgotten how beautiful he was.

And you know, It's got some fascinating material that certainly hasn't ever been seen.

Could you give me examples?

I loved seeing Grub when he was small—on the beach and swimming with the baboon and that sort of thing. It was just lovely. But it was the way the chimps came in. There they were; they were my old friends.

What is the number one thing that other documentaries get wrong about you?

It's just little things in these films that aren't true. The worst one was the very first Geographic film, Miss Goodall and the Wild Chimpanzees, which was so inaccurate it just wasn't true. (The original documentary included many staged shots; by comparison, Goodall has called Jane relatively uncensored and "unsanitized.") A lovely story, it was narrated by Orson Welles. And when they wanted it to be redone, he had broken his leg skiing. So they had to take the whole thing to a hospital in Switzerland—I love that story. [Laughs]

The new film places a particular focus on the benefits and challenges of being a pioneering woman in this field. For instance, you mention in the documentary that when you were starting out, it didn't hurt that you weren't ugly—and perhaps even helped you accomplish your goals.

Quite honestly, I didn't think of it back then. But it certainly helped The Geographic, I think, do more articles than they otherwise might have done—you know, a beauty and the beast sort of thing. Looking back on it, it was definitely an asset.

But recognition of your gender didn’t always help you. When you announced your discovery that chimps in the wild can create and modify tools, many scientists criticized your findings due to the fact that you were "a young untrained girl," as you say in the film. (Louis Leakey, the famed anthropologist who sponsored Goodall's work, purposefully chose Goodall in part because her mind was "uncluttered" by scientific theories of the time.) Sexism was also apparent in the coverage of your work, where you were often referred to as "swan-necked," and "comely." How did you react to all of this pushback?

At the time, I hated all the publicity. I tried to hide away from the media as much as I could. I was very shy.

Interestingly, it bothered me more much later on. When I did my PhD, I didn't do a lot of coursework like you do if you were doing a first degree. And so I thought I couldn't stand up and talk as an equal with these scientists in their white coats. At that point I began to think, "oh dear, I've got to change this perception of the 'Geographic cover girl', and people only listening to me because I've got nice legs. That's when I wrote that big book, Chimpanzees of Gombe. And I had to teach myself all the things I would have learned as an undergraduate.

Did you ever find it challenging not to have women role models who did the type of work you hoped to do?

Everybody in school—I was 10 when I wanted to go to Africa—they just laughed. How would I possibly get to Africa? I didn't have any money and I was a girl. But mum never indicated that I couldn't do something because of not being a man. She was an independent type and so was her mother. They were all pioneers in a way. Those were my role models, my family.

It was my dream, it was something I had always wanted to do, and now here was somebody giving me a chance to do it. I was jolly lucky that nobody had done it before, wasn't I? It meant that everything I saw was new.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Wei-Haas_Maya_Headshot-v2.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Wei-Haas_Maya_Headshot-v2.png)