Jane Goodall Reveals Her Lifelong Fascination With…Plants?

After studying chimpanzees for decades, the celebrated scientist turns her penetrating gaze on another life-form

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/The-Roots-of-a-Naturalist-631.jpg)

Editor's Note: There have been allegations of plagiarism in the book Seeds of Hope, from which this excerpt was drawn. Smithsonian has checked this material independently and ascertained to the best of our ability that everything published in the magazine and in this post is original.

From my window, as I write in my house in Bournemouth, England, I can see the trees I used to climb as a child. Up in the branches of one of them, a beech tree, I would read about Doctor Dolittle and Tarzan, and dream about the time when I, too, would live in the forest. I spent hours in that tree, perched in my special place. I had a little basket on the end of a long piece of string that was tied to my branch: I would load it before I climbed, then haul up the contents—a book, a saved piece of cake, sometimes my homework. I talked to “Beech,” telling him my secrets. I often placed my hands or my cheek against the slightly rough texture of his bark. And how I loved the sound of his leaves in summertime: the gentle whispering as the breeze played with them, the joyous abandoned dancing and rustling as the breeze quickened, and the wild tossing and swishing sounds, for which I have no words, when the wind was strong and the branches swayed. And I was part of it all.

Growing up in this idyllic home and landscape of England was the foundation of my lifelong love of the plant kingdom and the natural world. The other day, when I was looking through a box of childhood treasures that had been lovingly preserved by my mother, I came across a “Nature Notebook,” in which the 12-year-old Jane, with great attention to detail, had sketched and painted a number of local plants and flowers. Beside each drawing or watercolor I had handwritten a detailed description of the plant, based on my careful observations and probably a bit of book research. This was not a schoolbook. This wasn’t done for an assignment. I just loved to draw and paint and write about the plant world.

I used to read, curled up in front of the fire, on winter evenings. Then I traveled in my imagination to The Secret Garden with Mary and Colin and Dickon. I was entranced by C.S. Lewis’ Voyage to Venus, in which he describes, so brilliantly, flowers and fruits, tastes and colors and scents unknown on planet Earth. I raced through the skies with little Diamond, who was curled up in the flowing hair of the Lady North Wind, as she showed him what was going on in the world, the beauty and the sadness and the joy (At the Back of the North Wind). And, of course, I was utterly in love with Mole and Ratty and Mr. Badger in The Wind in the Willows. If The Lord of the Rings had been written when I was a child, there is no doubt I would have been entranced by Treebeard and the ancient forest of Fangorn, and Lothlórien, the enchanted forest of the elves.

And so I write now to acknowledge the enormous debt we owe to the plants and to celebrate the beauty, mystery and complexity of their world. That we may save this world before it is too late.

Roots

Wouldn’t it be fantastic if we had eyes that could see underground? So that we could observe everything down there in the same way we can look up through the skies to the stars. When I look at a giant tree I marvel at the gnarled trunk, the spreading branches, the multitude of leaves. Yet that is only half of the tree being—the rest is far, far down, penetrating deep beneath the ground.

There are so many kinds of roots. Aerial roots grow above the ground, such as those on epiphytes—which are plants growing on trees or sometimes buildings, taking water and nutrients from the air and rain—including many orchids, ferns, mosses and so on. Aerial roots are almost always adventitious, roots that can grow from branches, especially where they have been wounded, or from the tips of stems. Taproots, like those of carrots, act as storage organs. The small, tough adventitious roots of some climbing plants, such as ivy and Virginia creeper, enable the stems to cling to tree trunks—or the walls of our houses—with a viselike grip.

In the coastal mangrove swamps in Africa and Asia, I have seen how the trees live with their roots totally submerged in water. Because these roots are able to exclude salt, they can survive in brackish water, even that which is twice as saline as the ocean. Some mangrove trees send down “stilt roots” from their lowest branches; others have roots that send tubelike structures upward through the mud and water and into the air, for breathing.

Then there are those plants, such as the well-known mistletoe, beloved by young lovers at Christmastime but hated by foresters, that are parasitic, sending roots deep into the host tree to steal its sap. The most advanced of the parasitic plants have long ago given up any attempt at working for their own food—their leaves have become like scales, or are missing altogether.

The strangler fig is even more sinister. Its seeds germinate in the branches of other trees and send out roots that slowly grow down toward the ground. Once the end touches the soil it takes root. The roots hanging down all around the support tree grow into saplings that will eventually strangle the host. I was awestruck when I saw the famed temple at Angkor Wat in Cambodia, utterly embraced by the gnarled roots of a giant and ancient strangler fig. Tree and building are now so entwined that each would collapse without the support of the other.

The so-called clonal trees have remarkable root systems that seem capable of growing over hundreds of thousands of years. The most famous of them—Pando, or the Trembling Giant—has a root system that spreads out beneath more than 100 acres in Utah and has been there, we are told, for 80,000 to one million years! The multiple stems of this colony (meaning the tree trunks) age and die but new ones keep coming up. It is the roots that are so ancient.

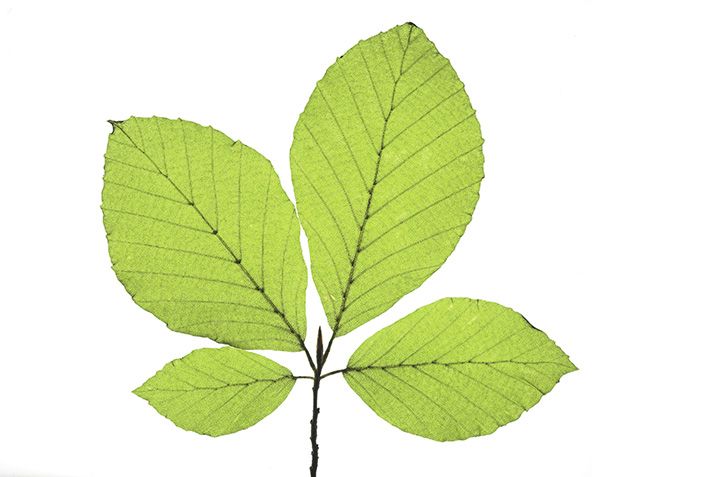

Leaves

The variety of leaves seems almost infinite. They are typically green from the chlorophyll that captures sunlight, and many are large and flat so as to catch the maximum amount. Indeed, some tropical leaves are so huge that people use them for umbrellas—and they are very effective, as I discovered during an aboriginal ceremony in Taiwan, when we were caught in a tropical downpour.

Orangutans have also learned to use large leaves during heavy rain. My favorite story concerns an infant, who was rescued from a poacher and was being looked after in a sanctuary. During one rainstorm she was sitting under the shelter provided but, after staring out, rushed into the rain, picked a huge leaf, and ran back to hold it over herself as she sat in the dry shelter.

Some leaves are delicate, some are tough and armed with prickles, yet others are long and stiff like needles. The often-vicious spines of the cactus are actually modified leaves—in these plants it is the stems that capture the energy from the sun. I used to think that the brilliant red of the poinsettia and the varied colors of bougainvillea were flowers, but, of course, they are leaves adapted to attract pollinating insects to the very small, insignificant-looking flowers in the center.

And then there are the most extraordinary leaves of that bizarre plant Welwitschia mirabilis. Each plant has only two leaves. They look like quite ordinary, long-shaped leaves on young plants, but they continue to grow, those exact same two leaves, for as long as the plant lives. Which may be more than 1,000 years. The Welwitschia was first discovered in Africa’s Namib Desert by Dr. Friedrich Welwitsch in 1859 and it is said that he fell to his knees and stared and stared, in silence. He sent a specimen to Sir Joseph Hooker, at Kew botanical gardens in London—and Sir Joseph for several months became obsessed with it, devoting hours at a time to studying, writing about and lecturing about the botanical oddity. It is, indeed, one of the most amazing plants on Earth, a living fossil, a relict of the cone-bearing plants that dominated the world during the Jurassic period. Imagine—this gangly plant, which Charles Darwin called “the duckbill of the vegetable kingdom,” has survived as a species, unchanged, for 135 million to 205 million years. Originally, its habitat was lush, moist forest, yet it has now adapted to a very different environment—the harsh Namib of southern Africa.

Seeds

If plants could be credited with reasoning powers, we would marvel at the imaginative ways they bribe or ensnare other creatures to carry out their wishes. And no more so than when we consider the strategies devised for the dispersal of their seeds. One such involves coating their seeds in delicious fruit and hoping that they will be carried in the bellies of animals to be deposited, in feces, at a suitable distance from the parent.

Darwin was fascinated by seed dispersal (well, of course—he was fascinated by everything) and he once recorded, in his diary, “Hurrah! A seed has just germinated after twenty one and a half hours in an owl’s stomach.” Indeed, some seeds will not germinate unless they have first passed through the stomach and gut of some animal, relying on the digestive juices to weaken their hard coating. The antelopes on the Serengeti plain perform this service for the acacia seeds.

In Gombe Stream National Park in western Tanzania, the chimpanzees, baboons and monkeys are marvelous dispersers of seeds. When I first began my study, the chimpanzees were often too far away for me to be sure what they were eating, so in addition to my hours of direct observation I would search for food remains—seeds, leaves, parts of insects or other animals—in their dung. Many field biologists around the world do the same.

Some seeds are covered in Velcrolike burs (Where do you think the idea of Velcro came from, anyway?) or armed with ferocious hooks so that a passing animal, willy-nilly, is drafted into servitude. Gombe is thick with seeds like this and I have spent hours plucking them from my hair and clothes. Sometimes my socks have been so snarled with barbs that by the time they are plucked out, the socks are all but useless. Some seeds are caught up in the mud that water birds carry from place to place on their feet and legs.

Is it not amazing that a small germ of life can be kept alive—sometimes for hundreds of years—inside a protective case where it waits, patiently, for the right conditions to germinate? Is it not stretching the imagination when we are told of a seed that germinated after a 2,000-year sleep? Yet this is what has happened.

The story begins with several seeds of the Judean date palm (Phoenix dactylifera) found by archaeologists studying the ruins of King Herod’s castle fortress Masada on the shores of the Dead Sea. Small fragments of the seedcase of two of these date seeds were used for carbon dating. The remaining three were planted—and of these one grew, a seedling that they named Methuselah after the biblical character, Noah’s grandfather, who was said to have lived for 969 years.

Although Methuselah is the oldest seed to have been woken from a long sleep, there are other very old seeds that have germinated, such as the single lotus seed (Nelumbo nucifera) found in China in an ancient lake bed and carbon-dated at 1,288 years, plus or minus 271 years. Another seed—of the flowering perennial Canna compacta, carbon-dated at about 600 years old—had survived for goodness knows how long in a walnut shell that was used for a ceremonial rattle.

And then there is the delightful story of some seeds collected in China in 1793 that were housed in the British Museum. These seeds, at least 147 years old, started to germinate in 1940 when they were accidentally “watered” by a hose used to extinguish a fire!

A miracle of a different sort took place when a couple of seeds of an extinct plant, Cylindrocline lorencei, a beautiful flowering shrub, were—quite literally—brought back from the dead. In 1996 only one individual plant remained, growing in the Plaine Champagne area of Mauritius. And then this last survivor died also. The only hope for saving the species lay in a few seeds that had been collected by botanist Jean-Yves Lesouëf 14 years before and stored in Brest Botanic Garden in France. Unfortunately, however, all attempts to germinate these seeds failed.

But plant people do not easily give up. Using new techniques, horticulturists found that small clusters of cells in the embryo tissue of just one or two of the seeds were still alive. Eventually, painstakingly, three clones were produced. And finally, in 2003, nine years from the beginning of their efforts, those three clones flowered—and produced seeds!

***

When I visited Kew, horticultu- ralist Carlos Magdalena showed me their plant, donated by the botanical gardens in Brest, derived from one of those original clones. As I looked at it I felt a sense of awe. What an example of the determination and perseverance of the horticulturists—and thank goodness for the intrepid botanists who have collected seeds around the world and, in so many cases, saved precious life-forms from extinction. Plans are now underway to return Cylindrocline lorencei to its faraway home on Mauritius.

While I was still gazing at this plant, Carlos smiled and said, “This is like if tomorrow we find a frozen mammoth in Siberia and even though the mammoth is dead, a few cells in the bone marrow are still alive and from it a whole mammoth can be cloned.”

Almost one year later, I heard how Russian scientists, led by Svetlana Yashina, had been able to regenerate a plant from fruit tissue that had been frozen in the Siberian permafrost for over 30,000 years! This plant, miraculously given new life, has been called Silene stenophylla. And, most exciting of all, it is fertile, producing white flowers and viable seeds.

It was found in a stash of plants and fruit in the burrow of an ice age squirrel 125 feet below the present surface of the permafrost. And in the same ice layer were the bones of large mammals, such as mammoth, woolly rhinoceros, bison, horse and deer. And the researchers claim that their success with S. stenophylla shows that tissue can survive in ice for tens of thousands of years and opens “the way to the possible resurrection of ice age mammals.” Carlos’ remark was uncannily prophetic.

Trees

I have always loved trees. I remember once, when I was about 6 years old, bursting into tears and frantically hitting an older cousin (with my little hands only) because he was stamping on a small sapling at the bottom of the garden. He told me he hated trees because they “made wind”! Even at 6 years I knew how wrong he was. I have already mentioned the trees in my childhood garden—the most special being a beech tree. I persuaded my grandmother to leave Beech to me in a last will and testament that I drew up, making it look as legal as I could, and she signed it for me on my 11th birthday.

In Gombe, when I walked alone up to the Peak—the observation point from which, using my binoculars, I could usually locate the chimpanzees—I would pause to talk to some of the trees I passed each day. There was the huge old fig tree, with great wide branches, laden with fruit and feasting chimpanzees, monkeys, birds and insects in the summer, and the very tall and upright mvule, or “dudu tree,” which attracted chimpanzees to feed on white galls made by a lace bug in the spring. Then there were the groves of the mgwiza, or “plum tree,” that grew near the streams, and the mbula and msiloti of the open woodlands, all of which provide, in their seasons, plentiful food for the chimpanzees—and other creatures too.

Of all the trees at Gombe it was the gnarled old fig tree that I loved best. How long had he stood there? How many rains had he known and how many wild storms had tossed his branches? With modern technology we could answer those questions. We even know, today, when the first trees appeared on planet Earth.

From the fossil record, it has been suggested that trees appeared about 370 million years ago, about 100 million years after the first plants had gained a foothold on the land. I can well imagine the excitement of the scientists working at a site in Gilboa, New York, who, in 2004, discovered a 400-pound fossil that was the crown of a fernlike tree. The following year they found fragments of a 28-foot-high trunk. And suddenly they realized the significance of the hundreds of upright fossil tree stumps that had been exposed during a flash flood over a century earlier. Those tree stumps were just a few miles away from their site and were estimated to be 385 million years old—the crown and the new trunk fragments were the same age. The newly discovered species Eospermatopteris is commonly known as Wattieza, which actually refers to the type of foliage.

It seems that these treelike plants spread across the land and began the work of sending roots down into the ground, breaking up the hard surface and eventually forming the first forests. And as their numbers increased they played an increasingly important role in removing C02 from the atmosphere and cooling Devonian temperatures. Thus they prepared things for the proliferation of land animals across the barren landscape of the early Devonian.

The Archaeopteris, which flourished in the late Devonian period, 385 to 359 million years ago, is the most likely candidate so far for the ancestor of modern trees. It was a woody tree with a branched trunk, but it reproduced by means of spores, like a fern. It could reach more than 30 feet in height, and trunks have been found with diameters of up to three feet. It seems to have spread rather fast, occupying areas around the globe wherever there were wet soils, and soon became the dominant tree in the spreading early forests, continuing to remove C02 from the atmosphere.

***

And then there are the “living fossils,” the cycads. They look like palms but are in fact most closely related to the evergreen conifers: pines, firs and spruces. They were widespread throughout the Mesozoic Era, 250 million to 65 million years ago—most commonly referred to as the “Age of the Reptiles,” but some botanists call it the “Age of the Cycads.” I remember Louis Leakey talking about them as we sat around the fire at Olduvai Gorge in the eastern Serengeti Plain, and imagining myself back in that strange prehistoric era. Today there are about 200 species throughout the tropical and semi- tropical zones of the planet.

Once the first forests were established both plant and animal species took off, conquering more and more habitats, adapting to the changing environment through sometimes quite extraordinary adaptations. Throughout the millennia new tree species have appeared, while others have become extinct due to competition or changing environments. Today there are an estimated 100,000 species of trees on planet Earth.

The oldest trees in the United Kingdom are English yews. Many of them are thought to be at least 2,000 years old—and it is quite possible that some individuals may have been on planet Earth for 4,000 years, the very oldest being the Fortingall Yew in Scotland. Yew trees were often planted in graveyards—they were thought to help people face death—and early churches were often built close to one of these dark, and to me, mysterious trees.

Almost every part of the yew is poisonous—only the bright red flesh around the highly toxic seed is innocent and delicious. It was my mother, Vanne, who taught my sister, Judy, and me that we could join the birds in feasting on this delicacy. How well I remember her telling us this as we stood in the dark, cool shade of a huge yew tree, whose thickly leaved branches cut out the brilliant sunshine outside. The tree grew outside an old church, but, the churchwarden told Vanne, the tree was far older than the church. We plucked the low-growing berries, separating out the soft flesh in our mouths and spitting out the deadly seed.

Of all the trees in the world, the one I would most like to meet, whose location is top-secret, is the Wollemi pine. It was discovered by David Noble, a New South Wales parks and wildlife officer, who was leading an exploration group in 1994, about 100 miles northwest of Sydney, Australia. They were searching for new canyons when they came across a particularly wild and gloomy one that David couldn’t resist exploring.

After rappelling down beside a deep gorge and trekking through the remote forest below, David and his group came upon a tree with unusual-looking bark. David picked a few leaves, stuck them in his backpack and showed them to some botanists after he got home. For several weeks the excitement grew, as the leaves could not be identified by any of the experts. The mystery was solved when it was discovered that the leaves matched the imprint of an identical leaf on an ancient rock. They realized the newly discovered tree was a relative of a tree that flourished 200 million years ago. What an amazing find—a species that has weathered no less than 17 ice ages!

The Tree That Survived 9/11

My last story comes from another dark chapter in human history. A day in 2001 when the World Trade Center was attacked, when the Twin Towers fell, when the world changed forever. I was in New York on that terrible day, traveling with my friend and colleague Mary Lewis. We were staying in mid-Manhattan at the Roger Smith Hotel. First came the confused reporting from the television screen. Then another colleague arrived, white and shaken. She had been on the very last plane to land before the airport closed, and she actually saw, from the taxi, the plane crashing into the second tower.

Disbelief. Fear. Confusion. And then the city went gradually silent until all we could hear was the sound of police car sirens and the wailing of ambulances. People disappeared from the streets. It was a ghost town, unreal.

It was eight days before there was a plane on which we could leave.

Ironically, we were flying to Portland, Oregon, where I had to give a talk, to a boys’ secondary school, entitled “Reason for Hope.” It was, without doubt, the hardest lecture I have ever had to give. Only when I was actually talking, looking out over all the young, bewildered faces, did I find the things to say, drawing on the terrible events of history, how they had passed, how we humans always find reserves of strength and courage to overcome that which fate throws our way.

Just over ten years after 9/11, on a cool, sunny April morning in 2012, I went to meet a Callery pear tree named Survivor. She had been placed in a planter near Building 5 of the World Trade Center in the 1970s and each year her delicate white blossoms had brought a touch of spring into a world of concrete. In 2001, after the 9/11 attack, this tree, like all the other trees that had been planted there, disappeared beneath the fallen towers.

But amazingly, in October, a cleanup worker found her, smashed and pinned between blocks of concrete. She was decapitated and the eight remaining feet of trunk were charred black; the roots were broken; and there was only one living branch.

The discovery was reported to Bram Gunther, who was then deputy director of central forestry for the New York City Parks Department, and when he arrived he initially thought the tree was unsalvageable. But the cleanup workers persuaded him to give the tree a chance, so he ordered that she be sent off to the Parks Department’s nursery in Van Cortlandt Park in the Bronx.

Ron Vega, now the director of design for the 9/11 Memorial site, was a cleanup worker back then. “A lot of people thought it was a wasted effort to try to rescue her,” he recalled. “So she was taken out of the site almost clandestinely—under the cover of night.”

Richie Cabo, the nursery manager, told me that when he first saw the decapitated tree he did not think anything could save her. But once the dead, burned tissues had been cut away, and her trimmed roots deeply planted in good rich soil, Survivor proved him wrong.

“In time,” said Richie, “she took care of herself. We like to say she got tough from being in the Bronx.”

In the spring of 2010 disaster struck Survivor again. Richie told me how he got news that the tree had been ripped out of the ground by a terrible storm that was raging outside, with 100 mile per hour winds. At once he rushed there with his three young children. They found the roots completely exposed, and he and the children and the other nursery staff worked together to try to rescue her.

At first they only partially lifted the tree, packing in compost and mulch so as not to break the roots. For a long while they gently sprayed the tree with water to minimize the shock, hoping she’d make it. A few weeks later they set to work to get Survivor completely upright.

“It was not a simple operation,” Richie told me. “She was 30 feet tall, and it took a heavy-duty boom truck to do the job.”

Again, Survivor survived.

It wasn’t until six years after Ron Vega witnessed the mangled tree being rescued from the wreckage that he heard Survivor was still alive. Immediately he decided to incorporate her into the memorial design—and with his new position he was able to make it happen. She was planted near the footprint of the South Tower. “For personal accomplishments,” Ron said, “today is it. I could crawl into this little bed and die right there. That’s it. I’m done....To give this tree a chance to be part of this memorial. It doesn’t get any better than that.”

As we walked toward this special tree, I felt as much in awe as though I were going to meet a great spiritual leader or shaman. We stood together outside the protective railing. We reached out to gently touch the ends of her branches. Many of us—perhaps all—had tears in our eyes.

As Survivor stood proudly upright in her new home, a reporter said to Richie, “This must be an extra-special day for you, considering it’s the ten-year anniversary of the day you were shot.”

Before he started working at the Bronx nursery in the spring of 2001, Richie had been a corrections officer at Green Haven maximum-security prison in New York. He left the job after nearly dying from a terrible gunshot wound in the stomach, inflicted not at the prison, but out on the streets when he tried to stop a robbery in progress.

Until the reporter pointed it out, Richie hadn’t even realized the date was the same. He told me that he couldn’t speak for a moment. “I could hardly even breathe,” he said. And he thought it was probably more than coincidence—that the tree would go home on that special day. “We are both survivors,” he said.

While overseeing the design, Ron made sure that the tree was planted so that the traumatized side faces the public. Some people, Ron told us, weren’t pleased to have the tree back, saying that she “spoiled” the symmetry of the landscaping, as she is a different species from the other nearby trees. Indeed, she is different. On the tenth anniversary of 9/11, when the memorial site was opened to survivors and family members, many of them tied blue ribbons onto Survivor’s branches.

One last memory. Survivor should have been in full bloom in April when I met her. But, like so many trees in this time of climate change, she had flowered about two weeks early. Just before we left, as I walked around this brave tree one last time, I suddenly saw a tiny cluster of white flowers. Just three of them, but somehow it was like a sign. It reminded me of a story I read in a newspaper. In the aftermath of the horrifying tsunami and Fukushima nuclear plant disaster in Japan, a TV crew went to document the situation. They interviewed a man who had just lost everything, not only his house and all his belongings, but his family also. The reporter asked him if he had any hope.

He turned and pointed to a cherry tree beginning to bloom. “Look there,” he said, pointing toward the new blossoms. “That’s what gives me hope.”