Jaron Lanier’s Virtual Reality Future

The father of virtual reality believed technology promised infinite possibilities. Now, he worries that it’s entrapping us

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20111028101012Carousel-of-Progress-VR-470x251.jpg)

As a kid in 1995, I remember going to Target to check out the latest and greatest in video game technology. I had read all about Nintendo’s new console, the Virtual Boy, in the gaming magazines that I was so enamored with at the time. The Virtual Boy had just hit the market that summer and I was lusting after one. It was a peculiar looking little unit: an unwieldy red and black headset that would cover your eyes and ostensibly transport you to other worlds. I peered into the display model and saw a familiar character, Mario (of “Brothers” fame), holding a tennis racquet. I don’t remember much about how the game played, but I do remember hating it and being quite disappointed.

In the 1990s, virtual reality offered the promise of a completely immersive experience—not just for games, but for completely reshaping the way we viewed the world. There were predictions that virtual reality would allow us to see inside things that it would be impossible for humans to otherwise venture into; allowing researchers to explore the human body or students to visit the bottom of the ocean floor. There were promises that we would one day never need leave our homes, for the world would be brought to us.

The January 1991 issue of Omni magazine includes an interview with Jaron Lanier, a man known in some circles as the father of virtual reality. The article paints Lanier as a man of vision, enthusiasm, and purpose, if a bit of an eccentric: “The Pied Piper of a growing technological cult, Lanier has many of the trappings of a young rock star: the nocturnal activity, attention-getting hair, incessant demands on his time.”

Lanier’s enthusiasm for the potential applications of this new technology jumps off the page. Interesting then, that Lanier’s 2010 book, You Are Not A Gadget: A Manifesto, strikes a slightly different tone, warning in many ways that technology may be building us into a corner from which we can’t escape. Lanier’s manifesto could be viewed as techno-reactionary, but it’s a special brand of reactionary thinking that comes into sharper focus when you read his Omni interview more closely. Back in 1991, Lanier explains that he ultimately wants his technology to open as many doors as possible; an ever-expansive tool for humanity that transcends the physical world:

As babies, each of us has an astonishing liquid infinity of imagination on the inside; that butts up against the stark reality of the physical world. That the baby’s imagination cannot be realized is a fundamental indignity that we only learn to live with when we decide to call ourselves adults. With virtual reality you have a world with many of the qualities of the physical world, but it doesn’t resist us. It release us from the taboo against infinite possibilities. That’s the reason virtual reality electrifies people so much.

While anyone with even a cursory knowledge of sci-fi movies of the 1990s (such as The Lawnmower Man) probably understands the fundamental cliches of virtual reality, it seems interesting that in 1991 the technology still needed to be explained in some detail. Lanier, for instance, describes how virtual reality’s “computerized clothing” works:

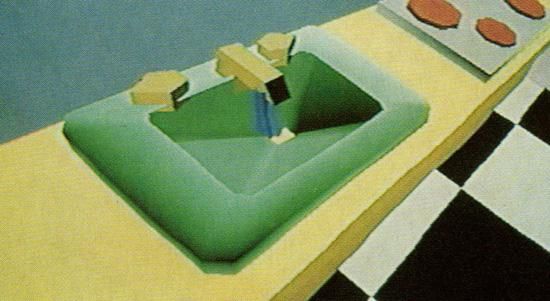

The goggles put a small TV in front of each eye so you see moving images in three dimensions. That’s only the beginning. There is one key trick that makes VR work: The goggles have a sensor allowing a computer to tell where your head is facing. What you see is created completely by the computer, which generates a new image every twentieth of a second. When you move your head to the left, the computer uses that information to shift the scene that you see to the right to compensate. This creates the illusion that your head is moving freely in a stationary space. If you put on a glove and hold your hand in front of your face, you see a computer-generated hand in the virtual world. If you wiggle your fingers, you see its fingers wiggle. The glove allows you to reach out and pick up an artificial object, say a ball, and throw it. Your ears are covered with earphones. The computer can process sounds, either synthesized or natural, so that they seem to come from a particular direction. If you see a virtual fly buzzing around, that fly will actually sound as though it’s coming from the right direction. We also make a full-body suit, a DataSuit, but you can just have a flying head, which isn’t really so bad. The hands and head are the business ends of the body — they interact most with the outside world. If you wear just goggles and gloves, you can do most of the stuff you want in the virtual world.

While I certainly don’t agree with every point Lanier makes in You Are Not a Gadget, I consider it essential reading. Unlike other techno-reactionary books of the last few years—such as Andrew Keen’s The Cult of the Amateur or Mark Bauerlein’s The Dumbest Generation—Lanier doesn’t seem to wish to turn back the clock. He still believes in the potential of high technology to do positive things, he just asks readers to take a step back and consider what a more humanistic version of our technologies might look like.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/matt-novak-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/matt-novak-240.jpg)