John James Audubon: America’s Rare Bird

The foreign-born frontiersman became one of the 19th century’s greatest wildlife artists and a hero of the ecology movement

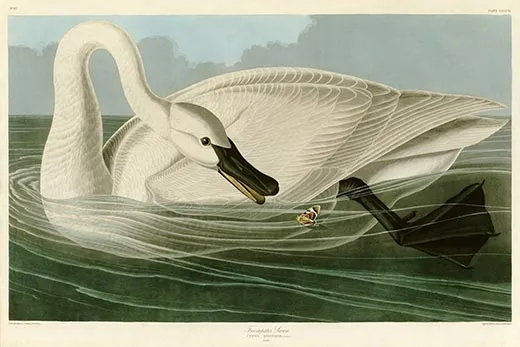

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/John-James-Audubon-Trumpeter-Swan-631.jpg)

The handsome, excitable 18-year-old Frenchman who would become John James Audubon had already lived his way through two names when he landed in New York from Nantes, France, in August 1803. His father, Jean, a canny ship’s captain with Pennsylvania property, had sent his only son off to America to escape conscription in the Napoleonic Wars. Jean Audubon owned a plantation near Valley Forge called Mill Grove, and the tenant who farmed it had reported a vein of lead ore. John James was supposed to evaluate the tenant’s report, learn what he could of plantation management, and eventually—since the French and Haitian revolutions had significantly diminished the Audubon fortune—make a life for himself.

He did that and much, much more. He married an extraordinary woman, opened a string of general stores on the Kentucky frontier and built a great steam mill on the Ohio River. He explored the American wilderness from GalvestonBay to Newfoundland, hunted with Cherokee and Osage, rafted the Ohio and the Mississippi. Throughout his travels, he identified, studied and drew almost 500 species of American birds. Singlehandedly, Audubon raised the equivalent of millions of dollars to publish a great, four-volume work of art and science, The Birds of America. He wrote five volumes of “bird biographies” chock-full of narratives of pioneer life and won fame enough to dine with presidents. He became a national icon—“the American Woodsman,” a name he gave himself. The record he left of the American wilderness is unsurpassed in its breadth and originality of observation; the Audubon Society, when it was initially founded in 1886, decades after his death, was right to invoke his authority. He was one of only two Americans elected Fellows of the Royal Society of London, the preeminent scientific organization of its day, prior to the American Civil War; the other was Benjamin Franklin.

John James had been born Jean Rabin, his father’s bastard child, in 1785 on Jean Audubon’s sugar plantation on Saint Domingue (soon to be renamed Haiti). His mother was a 27- year-old French chambermaid, Jeanne Rabin, who died of an infection within months of his birth. The stirrings of slave rebellion on the island in 1791 prompted Jean Audubon to sell what he could of his holdings and ship his son home to France, where his wife, Anne, whom Jean had married long before, welcomed the handsome boy and raised him as her own.

When the Reign of Terror that followed the French Revolution approached Nantes in 1793, the Audubons formally adopted Jean Rabin, to protect him, and christened him Jean Jacques or Fougère Audubon. Fougère—“Fern”—was an offering to placate the revolutionary authorities, who scorned the names of saints. Jean-Baptiste Carrier, a revolutionary envoy sent out from Paris to quell the peasant counterrevolution in western France, ordered the slaughter of thousands in Nantes, a principal city in the region. Firing squads bloodied the town square. Other victims were chained to barges and sunk in the Loire; their remains tainted the river for months. Though Jean Audubon was an officer in the Revolutionary French Navy, he and his family were dungeoned. After the terror, he moved his family downriver to a country house in the riverside village of Couëron. Now his only son was escaping again.

The young country to which John James Audubon immigrated in the summer of 1803 was barely settled beyond its eastern shores; Lewis and Clark were just then preparing to depart for the West. France in that era counted a population of more than 27 million, Britain about 15 million, but only 6 million people thinly populated the United States, two-thirds of them living within 50 miles of Atlantic tidewater. In European eyes America was still an experiment. It would need a second American revolution—the War of 1812—to compel England and Europe to honor American sovereignty.

But the generation of Americans that the young French émigré was joining was different from its parents’. It was migrating westward and taking great risks in pursuit of new opportunities its elders had not enjoyed. Audubon’s was the era, as the historian Joyce Appleby has discerned, when “the autonomous individual emerged as an [American] ideal.” Individualism, Appleby writes, was not a natural phenomenon but “[took] shape historically [and] came to personify the nation.” And no life was at once more unusual and yet more representative of that expansive era when a national character emerged than Audubon’s. Celebrate him for his wonderful birds, but recognize him as well as a characteristic American of the first generation—a man who literally made a name for himself.

Lucy Bakewell, the tall, slim, gray-eyed girl next door whom he married, came from a distinguished English family. Erasmus Darwin, a respected physician, poet and naturalist and grandfather to Charles, had dandled her on his knee in their native Derbyshire. Her father had moved his family to America when she was 14 to follow Joseph Priestley, the chemist and religious reformer, but opportunity had also drawn the Bakewells. Their Pennsylvania plantation, Fatland Ford, was more ample than the Audubons’, and William Bakewell sponsored one of the first experiments in steampowered threshing there while his young French neighbor lay ill with a fever in his house and under his talented daughter’s care. Lucy was a gifted pianist, an enthusiastic reader and a skillful rider—sidesaddle—who kept an elegant house. She and John James, once they married and moved out to Kentucky in 1808, regularly swam across and back the half-milewide Ohio for morning exercise.

Lucy’s handsome young Frenchman had learned to be a naturalist from his father and his father’s medical friends, exploring the forested marshes along the Loire. Lucy’s younger brotherWill Bakewell left a memorable catalog of his future brother-in-law’s interests and virtues; even as a young man, Audubon was someone men and women alike wanted to be around:

“On entering his room, I was astonished and delighted to find that it was turned into a museum. The walls were festooned with all kinds of birds’ eggs, carefully blown out and strung on a thread. The chimney-piece was covered with stuffed squirrels, raccoons, and opossums; and the shelves around were likewise crowded with specimens, among which were fishes, frogs, snakes, lizards, and other reptiles. Besides these stuffed varieties, many paintings were arrayed on the walls, chiefly of birds. . . . He was an admirable marksman, an expert swimmer, a clever rider, possessed of great activity [and] prodigious strength, and was notable for the elegance of his figure and the beauty of his features, and he aided nature by a careful attendance to his dress. Besides other accomplishments he was musical, a good fencer, danced well, and had some acquaintance with legerdemain tricks, worked in hair, and could plait willow baskets.”

In 1804, Audubon was curious whether the eastern phoebes that occupied an old nest above a Mill Grove cave were a pair returned from the previous year. “When they were about to leave the nest,” Audubon wrote, “I fixed a light silver thread to the leg of each.” His experiment was the first recorded instance in America of birdbanding, a now routine technique for studying bird migration. Two of the phoebes that returned the following spring still carried silver threads. One, a male, remembered Audubon well enough to tolerate his presence near its nest, though its mate shied away.

Audubon had begun teaching himself to draw birds in France. Operating general stores in Louisville and then downriver in frontier Henderson, Kentucky, he was responsible for keeping the cooking pot filled with fish and game and the shelves with supplies while his business partner ran the store and Lucy kept house, worked the garden and bore John James two sons. As he hunted and traveled, he improved his art on American birds and kept careful field notes as well. His narrative of an encounter with a flood of passenger pigeons in Kentucky in autumn 1813 is legendary. He gave up trying to count the passing multitudes of the grayish blue, pink-breasted birds that numbered in the billions at the time of the European discovery of America and now are extinct. “The air was literally filled with Pigeons,” he wrote of that encounter; “the light of noon-day was obscured as by an eclipse; the dung fell in spots, not unlike melting flakes of snow; and the continued buzz of wings had a tendency to lull my senses to repose.” His observations match his best drawings in vivacity: of chimney swifts lining a hollow sycamore stump near Louisville like bats in a cave, brown pelicans fishing the shallows of the Ohio, sandhill cranes tearing away waterlily roots in a backwater slough, and robins down from Labrador occupying apple trees. He saw bald eagles that nested by the hundreds along the Mississippi swooping like falling stars to strike swans to the ground. Crowds of black vultures, protected by law, patrolled the streets of Natchez and Charleston to clean up carrion and roosted at night on the roofs of houses and barns. Bright scarlet, yellow and emerald green Carolina parakeets, now extinct, completely obscured a shock of grain like “a brilliantly colored carpet” in the center of a field, and a least bittern stood perfectly still for two hours on a table in his studio while he drew it.

Not many of the birds Audubon drew stood still for him, nor had cameras or binoculars yet been invented. To study and draw birds it was necessary to shoot them. Audubon’s predecessors typically skinned their specimens, preserved the skins with arsenic, stuffed them with frayed rope and set them up on branches to draw them. The resulting drawings looked as stiff and dead as their subjects. Audubon dreamed of revivifying his specimens—even the colors of their feathers changed within 24 hours of death, he said—and at Mill Grove, still a young man, he found a way to mount freshly killed specimens on sharpened wires set into a gridded board that allowed him to position them in lifelike attitudes. He drew them first, then filled in his drawings with watercolor that he burnished with a cork to imitate the metallic cast of feathers. After drawing, he often performed an anatomical dissection. Then, because he usually worked deep in the wilderness, far from home, he cooked and ate his specimens. Many of the descriptions in his Ornithological Biography mention how a species tastes—testimony to how quickly the largely self-taught artist drew. “The flesh of this bird is tough and unfit for food,” he writes of the raven. The green-winged teal, on the other hand, has “delicious” flesh, “probably the best of any of its tribe; and I would readily agree with any epicure in saying, that when it has fed on wild oats at Green Bay, or on soaked rice in the fields of Georgia and the Carolinas, for a few weeks after its arrival in those countries, it is much superior to the Canvass-back in tenderness, juiciness and flavor.”

Though drawing birds had been something of an obsession, it was only a hobby until Audubon’s mill and general stores went under in the Panic of 1819, a failure his critics and many of his biographers have ascribed to a lack of ability or irresponsible distraction by his art. But nearly every business in the trans-Appalachian West failed that year, because the Western state banks and the businesses they serviced were built on paper. “One thing seems to be universally conceded,” an adviser told the governor of Ohio, “that the greater part of our mercantile citizens are in a state of bankruptcy—that those of them who have the largest possessions of real and personal estate . . . find it almost impossible to raise sufficient funds to supply themselves with the necessaries of life.” The Audubons lost everything except John James’ portfolio and his drawing and painting supplies. Before he declared bankruptcy, Audubon was even briefly thrown in jail for debt.

Through these disasters, Lucy never failed him, although they lost an infant daughter to fever the following year. “She felt the pangs of our misfortunes perhaps more heavily than I,” Audubon remembered gratefully of his stalwart love, “but never for an hour lost her courage; her brave and cheerful spirit accepted all, and no reproaches from her beloved lips ever wounded my heart. With her was I not always rich?”

Audubon took up portrait drawing at $5 a head. His friends helped him find work painting exhibit backgrounds and doing taxidermy for a new museum in Cincinnati modeled on painter Charles Wilson Peale’s famous museum in Philadelphia, which Audubon knew from his Mill Grove days. Peale’s PhiladelphiaMuseum displayed stuffed and mounted birds as if alive against natural backgrounds, and preparing such displays in Cincinnati probably pointed Audubon to his technical and aesthetic breakthrough of portraying American birds in realistic, lifelike settings. Members of a government expedition passing through Cincinnati in the spring of 1820, including the young artist Titian Ramsey Peale, son of the Philadelphia museum keeper, alerted Audubon to the possibility of exploring beyond the Mississippi, the limit of frontier settlement at that time. Daniel Drake, the prominent Cincinnati physician who had founded the new museum, praised Audubon’s work in a public lecture and encouraged him to think of adding the birds of the Mississippi flyway to his collection, extending the range of American natural history; the few ornithologists who had preceded Audubon had limited their studies to Eastern species.

By spring 1820, Drake’s museum owed Audubon $1,200, most of which it never paid. The artist scraped together such funds as he could raise from drawing and teaching art to support Lucy and their two boys, then 11 and 8, who moved in with relatives again while he left to claim his future. He recruited his best student, 18-year-old Joseph Mason, to draw backgrounds, bartered his hunting skills for boat passage on a commercial flatboat headed for New Orleans, and in October floated off down the Ohio and the Mississippi.

For the next five years Audubon labored to assemble a definitive collection of drawings of American birds while struggling to support himself and his family. He had decided to produce a great work of art and ornithology (a decision that Lucy’s relatives condemned as derelict): The Birds of America would comprise 400 two- by three-foot engraved, hand-colored plates of American birds “at the size of life” to be sold in sets of five, and collected into four huge, leather-bound volumes of 100 plates each, with five leather-bound accompanying volumes of bird biographies worked up from his field notes.

He had found a paradise of birds in the deciduous forests and bluegrass prairies of Kentucky; he found another paradise of birds in the pine forests and cypress swamps of Louisiana around St. Francisville in West Feliciana Parish, north of Baton Rouge, inland from the river port of Bayou Sarah, where prosperous cotton planters hired him to teach their sons to fence and their daughters to draw and to dance the cotillion. Elegant Lucy, when finally he was able to move her and the boys south to join him there, opened a popular school of piano and deportment on a cotton plantation operated by a hardy Scottish widow.

On his first inspection of the St. Francisville environs, Audubon identified no fewer than 65 species of birds. He probably collected there the bird he rendered in what would become his best-known image, the prized first plate of The Birds of America—a magnificent specimen of wild turkey cock that he had called from a Mississippi canebrake with a caller made from a wing bone.

Finally, in May 1826, Audubon was ready to find an engraver for his crowded portfolio of watercolor drawings.He would have to travel to Europe; no American publisher yet commanded the resources to engrave, hand color and print such large plates. Forty-one years old, with the equivalent of about $18,000 in his purse and a collection of letters of introduction from New Orleans merchants and Louisiana and Kentucky politicians, including Senator Henry Clay, he sailed from New Orleans on a merchant ship bound for Liverpool with a load of cotton. He was trusting to charm, luck and merit; he knew hardly anyone in England. In Liverpool, Lucy’s younger sister Ann and her English husband, Alexander Gordon, a cotton factor, took one look at Audubon’s rough frontier pantaloons and unfashionable shoulder-length chestnut hair (about which he was comically vain) and asked him not to call again at his place of business. But James Fenimore Cooper’s The Last of the Mohicans had been published in London in April and was blooming to a nationwide fad, and some who met Audubon in Liverpool judged him a reallife Natty Bumppo. The letters he carried introduced him to the first family of Liverpool shipping, the Rathbones, Quaker abolitionists who recognized his originality and sponsored him socially. Within a month, he was a celebrity, his presence sought at every wealthy table; his in-laws soon came round.

“The man . . . was not a man to be seen and forgotten, or passed on the pavement without glances of surprise and scrutiny,” an anonymous contemporary wrote. “The tall and somewhat stooping form, the clothes not made by a Westend but a Far West tailor, the steady, rapid, springing step, the long hair, the aquiline features, and the glowing angry eyes—the expression of a handsome man conscious of ceasing to be young, and an air and manner which told you that whoever you might be he was John Audubon, will never be forgotten by anyone who knew or saw him.” Not only Audubon’s novelty won him attention in Liverpool and then in Manchester, Edinburgh and London. Britain was the most technologically advanced nation in the world in 1826, with gaslights illuminating its cities, steam mills weaving cotton, steamboats plying its ports and railroad lines beginning to replace its mature network of canals, but the only permanent images then available in the world were originally drawn by hand. Traveling from city to city, Audubon would hire a hall and fill it with his life-size watercolors of birds luminescent against their backgrounds of wilderness, hundreds of images at a time, and charge admission to the visitors who flocked to see them. AFrench critic who saw the drawings in Edinburgh was entranced:

“Imagine a landscape wholly American, trees, flowers, grass, even the tints of the sky and the waters, quickened with a life that is real, peculiar, trans-Atlantic. On twigs, branches, bits of shore, copied by the brush with the strictest fidelity, sport the feathered races of the New World, in the size of life, each in its particular attitude, its individuality and peculiarities. Their plumages sparkle with nature’s own tints; you see them in motion or at rest, in their plays and their combats, in their anger fits and their caresses, singing, running, asleep, just awakened, beating the air, skimming the waves, or rending one another in their battles. It is a real and palpable vision of the New World, with its atmosphere, its imposing vegetation, and its tribes which know not the yoke of man. . . . And this realization of an entire hemisphere, this picture of a nature so lusty and strong, is due to the brush of a single man; such an unheard-of triumph of patience and genius!”

So many scenes of birds going about their complicated lives would have flooded viewers’ senses as an IMAXTheater presentation floods viewers today, and all the more so because the world these creatures inhabited was America, still largely wilderness and a romantic mystery to Europeans, as Audubon discovered to his surprise. He answered questions about “Red Indians” and rattlesnakes, and imitated war whoops and owl hoots until he could hardly bear to accept another invitation.

But accept he did, because once he found an engraver in London worthy of the great project, which he had calculated would occupy him for 16 years, the prosperous merchants and the country gentry would become his subscribers, paying for the five-plate “Numbers” he issued several times a year and thus sustaining the enterprise. (When the plates accumulated to a volume, the subscribers had a choice of bindings, or they could keep their plates unbound. One titled lady used them for wallpaper in her dining room.)

Audubon thus produced The Birds of America pay as you go, and managed to complete the work in only ten years, even though he had to increase the total number of plates to 435 as he identified new species on collecting expeditions back to the Carolinas and East Florida, the Republic of Texas, northeastern Pennsylvania, Labrador and the JerseyShore. In the end, he estimated that the four-volume work, issued in fewer than 200 copies, cost him $115,640—about $2,141,000 today. (One fine copy sold in 2000 for $8,802,500.) Unsupported by gifts, grants or legacies, he raised almost every penny of the immense cost himself from painting, exhibiting and selling subscriptions and skins. He paced the flow of funds to his engraver so that, as he said proudly, “the continuity of its execution” was not “broken for a single day.” He paced the flow of drawings as well, and before that the flow of expeditions and collections. He personally solicited most of his subscribers and personally serviced most of his accounts. Lucy supported herself and their children in Louisiana while he was establishing himself; thereafter he supported them all and the work as well. If he made a profit, it was small, but in every other way the project was an unqualified success. After he returned to America, he and his sons produced a less costly octavo edition with reduced images printed by lithography. The octavo edition made him rich. These facts should lay to rest once and for all the enduring canard that John James Audubon was “not a good businessman.” When he set out to create a monumental work of art with his own heart and mind and hands, he succeeded— a staggering achievement, as if one man had single-handedly financed and built an Egyptian pyramid.

He did not leave Lucy languishing in West Feliciana all those years, but before he could return to America for the first time to collect her, their miscommunications, exacerbated by the uncertainties and delays of mail delivery in an era of sailing ships, nearly wrecked their marriage. Lonely for her, he wanted her to close her school and come to London; she was willing once she had earned enough to keep their sons in school. But a round of letters took six months, and one ship in six (and the letters it carried) never made port. By 1828 Audubon had convinced himself that Lucy expected him to amass a fortune before she would leave Louisiana, while she feared her husband had been dazzled by success in glamorous London and didn’t love her anymore. (Audubon hated London, which was fouled with coal smoke.) Finally, she insisted that he come in person to claim her, and after finding a trustworthy friend to handle a year’s production of plates for Birds, he did, braving the Atlantic, crossing the mountains to Pittsburgh by mail coach, racing down the Ohio and the Mississippi by steamboat to Bayou Sarah, where he disembarked in the middle of the night on November 17, 1829. Lucy had moved her school to William Garrett Johnson’s Beech Grove plantation by then, 15 miles inland; that was where Audubon was headed:

“It was dark, sultry, and I was quite alone. I was aware yellow fever was still raging at St. Francisville, but walked thither to procure a horse. Being only a mile distant, I soon reached it, and entered the open door of a house I knew to be an inn; all was dark and silent. I called and knocked in vain, it was the abode of Death alone! The air was putrid; I went to another house, another, and another; everywhere the same state of things existed; doors and windows were all open, but the living had fled. Finally I reached the home of Mr. Nübling, whom I knew. He welcomed me, and lent me his horse, and I went off at a gallop. It was so dark that I soon lost my way, but I cared not, I was about to rejoin my wife, I was in the woods, the woods of Louisiana, my heart was bursting with joy! The first glimpse of dawn set me on my road, at six o’clock I was at Mr. Johnson’s house; a servant took the horse, I went at once to my wife’s apartment; her door was ajar, already she was dressed and sitting by her piano, on which a young lady was playing. I pronounced her name gently, she saw me, and the next moment I held her in my arms. Her emotion was so great I feared I had acted rashly, but tears relieved our hearts, once more we were together.”

And together they remained, for the rest of their lives. If Audubon’s life resembles a 19th-century novel, with its missed connections, Byronic ambitions, dramatic reversals and passionate highs and lows, 19th-century novels were evidently more realistic than moderns have understood. Besides his art, which is as electrifying on first turning the pages of The Birds of America today as it was two centuries ago— no one has ever drawn birds better—Audubon left behind a large collection of letters, five written volumes, two complete surviving journals, fragments of two more, and a name that has become synonymous with wilderness and wildlife preservation. “All, but the remembrance of his goodness, is gone forever,” Lucy wrote sadly of her husband’s death, at age 65, from complications of dementia in January 1851. For Lucy all was gone—she lived on until 1874—but for the rest of us, wherever there are birds there is Audubon, a rare bird himself, a bird of America.