Bryan Johnson arrived at the wild blueberry camps on a warm August night in 2023. It was around 1 a.m. Exhausted from the nine-hour journey in his friend’s truck, he fell asleep on the floor of the mess hall. Someone shook him awake around 5 asking, “Are you here to work?” He nodded yes.

Johnson, a 42-year-old Mi’kmaq fisherman of the Eskasoni First Nation, in Nova Scotia, Canada, had grown up hearing about harvesting blueberries in Maine. His parents and grandmother came down every summer to work for several weeks, saving their earnings for school clothes and other expenses. Everyone he knows in Eskasoni had, at one point, made the trip for the harvest—simultaneously a working vacation, a source of extra income and a cultural ritual. But with a wife and seven kids at home, it was hard to get away. When he finally found the time, he hit the road with nothing but a sleeping bag and a few sets of clothes. “I was scared,” he told me. “I was scared that I would have no place to sleep. I was scared that I wouldn’t have a rake. I was scared that I went there for nothing. But I had faith in good people.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/5f/b8/5fb85d37-80ad-45b0-bd60-94ab8b63c554/julaug2024_f11_blueberries.jpg)

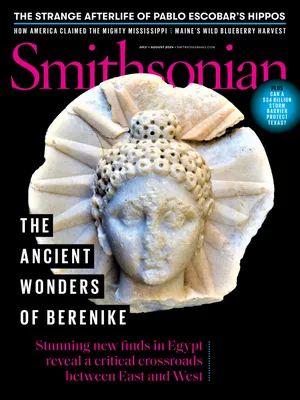

Johnson is one of thousands of people who show up in rural northeastern Maine every August to harvest wild blueberries. Many stay in one of several company-owned camps right in the middle of the blueberry barrens, as these 46,000-odd acres of fields are called. The harvest is a remarkable convergence of people from across the continent, including those native to the region on both sides of the Canadian-American border and migrant farmworkers from Central America and the Caribbean. The blueberries they harvest are distinct from those you might see year-round in the supermarket. The most common commercially grown blueberry is the highbush, a tall native shrub that can be planted and cultivated in different climates. By contrast, wild blueberries are not planted but grow naturally as a ground cover from North Carolina to Canada. They thrive especially well in the coarse, acidic soils of northeastern, or “Down East,” Maine.

Smaller and sweeter than high-bush blueberries, wild blueberries are high in antioxidants and are considered one of the most nutritious foods on earth. For thousands of years, the five tribal nations of the Wabanaki peoples—the Mi’kmaq, Maliseet, Passamaquoddy, Penobscot and Abenaki—have harvested these wild blueberries in late summer. Traditionally, they used their hands or hand-held rakes, which look something like a dustpan with fine metal teeth. The berries are a part of their seasonal foodways, eaten fresh, preserved for winter, stewed into tea and cough syrup, and used as a dye.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/9a/82/9a82a592-3b9e-4b2c-a9ae-45d20ec950ed/julaug2024_f12_blueberries.jpg)

The Wabanaki, whose ancestral homelands stretch across eastern Canada and New Hampshire, Maine and Vermont, have long encouraged wild blueberry growth through prescribed burning, a practice later adopted by Europeans who settled on their lands. During the American Civil War, the blueberries were used to feed the Union Army, soon driving a robust canning industry. Since then, the wild blueberry industry has been central to both the economy and culture of Maine, contributing tens of millions of dollars to the state’s economy each year. But commercial growers around the world are increasingly planting highbush blueberries year-round, crowding the market. And in Maine, wild blueberry farmers are switching to large harvesting machines to keep up with industry competition at the same time as climate change is leading to earlier harvests, high heat, periodic drought and a decline in native bee populations that are essential for pollination. These shifting economic, ecological and social conditions have led to a precarious future for this traditional harvest.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/0d/a6/0da64ff5-3a65-4ef0-b8cc-7f0b19c54ded/julaug2024_f13_blueberries.jpg)

As a sociologist studying the effects of climate change on rural livelihoods, I wanted to understand how shifting weather patterns might be changing this industry. But I also wanted to experience firsthand the unusual mingling of cultures the harvest relies upon. The demographics have shifted significantly in the last several decades. Several thousand migrant and seasonal workers, including Wabanaki harvesters, now participate in the wild blueberry harvest, either hand-raking blueberries, processing and freezing berries, or driving harvesting machines. Although reliable demographic data is sparse, the most recent survey, conducted by the Maine Department of Labor in 2015, suggests that seasonal and migrant workers make up around 17 percent of all hired farm labor in Maine. Most were born in Mexico; others come from Haiti, Honduras and El Salvador. In addition to perhaps hundreds of Wabanaki harvesters, many workers follow the growing seasons up the East Coast, harvesting fruit and vegetables. Some stay in Maine through the winter, collecting balsam fir branches for wreaths, or working in the seafood processing industry.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/0f/18/0f18d6c7-2a77-4c85-83a6-84380ecfc6bd/julaug2024_f14_blueberries.jpg)

While their labor is essential, their work often goes unacknowledged in this predominantly white state. “I don’t think a lot of people know who are the folks picking the food for them in the field,” says Juana Rodriguez Vazquez, executive director of Mano en Mano, an organization that connects immigrants and farmworkers in Maine to essential services such as housing and health care. “I don’t think it’s often valued as it should be.” April Norton, of Wyman’s, among the largest producers of wild blueberries in the state, told me, “Our migrant and seasonal workforce is critical to the viability of our organization. Without them we would not get this harvest.”

I visited the blueberry barrens during the first week of the harvest, arriving at the Passamaquoddy Wild Blueberry Company headquarters, in Columbia Falls, at 7 a.m. The company, owned and operated by the Passamaquoddy Tribe, cultivates 2,000 acres of blueberry fields.

The land is just a portion of ancestral territory seized first by Massachusetts and then Maine beginning in the 17th century. It was repurchased by the tribe in the 1980s, using funds earmarked by Congress after lawmakers approved a settlement between Maine and Wabanaki tribes. (The two sides remain at odds over aspects of the settlement’s implementation, including a provision that hinders Wabanaki citizens of Maine from accessing federal benefits established for Indian tribes.)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/e9/a0/e9a08794-0de0-448f-b8e8-f9d10b55e637/julaug2024_f07_blueberries.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/fb/e1/fbe14aa8-7fe0-456a-890a-ef37027421a6/julaug2024_f01_blueberries.jpg)

At the camp, I met Darren Paul, the company’s general manager, who led me to a shed full of hand rakes. We found one that seemed to fit my hand and wasn’t too heavy, then hopped in his truck. Soon, a company camp came into view, a collection of 20 simple wood cabins that house rakers and their families during the harvest. Picnic tables and lawn chairs were set up outside. In a cabin decorated with strings of lights, I met Stephanie Bailey, 50, a Passamaquoddy harvest supervisor from Indian Township (known as Motahkomikuk in Passamaquoddy), an hour north of here. In Bailey’s kitchen, I sat at a picnic table with Connor, a Passamaquoddy teenager also from Indian Township who, like me, was preparing for his first harvest, and a family from the Eskasoni First Nation, who have come for the past 40 years. When the family shared that they have stayed in the same cabin for the last 20 years, Bailey beamed. “I love that so much,” she said. Before we could begin raking, Bailey taught us about how to spray pesticides and how to avoid spreading them from berries to our skin. I asked Connor what he knew about the history of blueberry harvesting and his people. “Nothing,” he said.

This wasn’t surprising. Bailey recalled that her grandfather was punished by church authorities for hunting and foraging for his meals, part of a legacy of government-sponsored attempts dating to 1879 to replace Indigenous cultures with Christian culture. As recently as the 1970s, Wabanaki children were forced to attend boarding schools where they were forbidden from speaking their native languages or otherwise expressing their culture, and were frequently subjected to physical, emotional and sexual abuse. Even in schools on the reservation, Wabanaki people were prohibited from speaking their native languages or eating traditional foods. “We were literally taught you’re going to go to jail if you provide for yourself in the way that we’ve done it for thousands of years,” Bailey told me. This was hardly an unusual practice, as the Potawatomi Nation scholar Kyle Powys Whyte wrote in 2017. “One of the common strategies of erasure is to erase Indigenous people’s food systems.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/04/68/046810aa-1804-44fc-b7d5-9bdcf21b45ee/julaug2024_f09_blueberries.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/29/a7/29a77826-721e-4486-b773-29a3688a2fb8/julaug2024_f08_blueberries.jpg)

In 2013, in an attempt to redress ongoing wrongs, Maine Governor Paul LePage and chiefs from five Wabanaki tribes established a first-of-its-kind Truth and Reconciliation Commission in the United States, which jointly investigated the state’s continued removal of Wabanaki children from their communities. For example, between 2000 and 2013, the commission found, Maine’s child welfare agency separated Wabanaki children from their families via the foster care system at a rate up to five times higher than non-Native children.

On his first day at the harvest, Johnson, the fisherman from Nova Scotia, was handed a rake. Then a few other harvesters showed him how to bend over, scooping using first his back, then his legs—“like a crab or something,” he told me. Blueberry workers make a set amount of money per box, which each weighs about 20 pounds when filled. The rate for a box varies slightly from company to company, but overall rates across the industry have remained virtually unchanged for three decades. At the Passamaquoddy Wild Blueberry Company, it’s currently set at $2.75. Johnson could not believe how hard the work was, but he filled 55 boxes of blueberries on his first day. Back at camp, there was a bonfire and a potluck dinner. Families played outside. Johnson told me that apart from a joke some of the guys made about how a bear was going to get him on his way to the outhouse—a threat that never materialized—he didn’t worry about much. “I went there with nothing, and people were feeding me,” he said. “I couldn’t believe how nice they were. It felt good to be there. I felt like I reconnected with my ancestors.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/01/ce/01ceaf09-adbf-48e6-bdc8-93b01f882d88/julaug2024_f03_blueberries.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/2b/a3/2ba351af-def7-4561-8fee-f6cd22901c9e/julaug2024_f04_blueberries.jpg)

On my first day out in the fields, I met John Googoo, a crew supervisor. Googoo gave me a lesson in the two raking styles: scooping and sweeping. Sweeping is for advanced rakers, who crouch and “sweep” the rake at an angle across their body, a long glide across the top of the berries, almost a dance. Scooping is a shorter movement, reaching the rake’s teeth underneath the berries, then pulling back up toward your body. Googoo said that most rakers fill between 40 and 50 boxes each day. I said I was going for five. He got four boxes for me and set them on the ground. As he walked away, I picked up the rake and gave it a try, but I mainly pulled up rocks and soil. Next I positioned the fingers of the rake slightly higher, but I still ended up raking the ground. Googoo’s wife, Brenda, rushed over. “Try not to dig up the whole plant,” she said.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/86/0a/860a60ec-7b1d-4596-83cd-f83aaa5beb87/julaug2024_f10_blueberries.jpg)

It finally clicked that it’s called scooping because you have to move the rake downward at an angle, then pull it back up and toward you, like scooping ice cream. I moved up and across the field, scooping and lifting, dropping the berries in the boxes and pulling out errant grasses. On either side of me, harvesters chatted in Mi’kmaq and Spanish. Although the Passamaquoddy Wild Blueberry Company mostly cultivates conventional wild blueberries now, to keep up with the industry, I was put on an organic blueberry field. Without pesticides, these sections are full of weeds and are considered much harder work. By the end of the day, I had filled 15 boxes of berries and could barely walk.

The next morning, I visited the Blueberry Harvest School, run by Mano en Mano, in Milbridge. The school operates as a hub for working families during the three-week harvest, transporting dozens of students from blueberry company camps and several nearby towns. While their parents are in the fields, the children read, visit the playground, have class in the woods, and take field trips to local beaches and water parks. Remarkably, the school offers instruction in three languages: Spanish, English and Mi’kmaq/Passamaquoddy (although distinct, the languages are very similar).

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/c7/16/c7162777-b489-4bd2-804a-8d4da3d958b3/julaug2024_f05_blueberries.jpg)

In Maggie Burgos’ combined second- and third-grade class, students colored, played Legos and read books as they settled into their day. “There’s a lot of movement in what their families do for work,” she said. “I’ve heard from a lot of students that coming to Blueberry Harvest School feels like a constant in their year.” Once each student arrived, the class gathered in a circle on soft floor mats. We each took a turn saying our name and the language we felt most comfortable speaking. For most students this was Mi’kmaq or Spanish. Burgos then read a book about weaving traditions around the world. Wabanaki peoples are renowned for their baskets, often woven from strips of brown ash trees and gathered sweetgrass. In the afternoon, the students practiced making their own weavings with paper before moving on to cloth. Finally, Burgos asked each student to name one thing that they love. One student, a Mi’kmaq boy who had been fidgeting on his mat, said, “I love everyone in this classroom.”

In recent years, as spring and fall have become warmer, the blueberry season has shifted, too. Harvests used to be exclusively in August. Some rakers recall once waking up to trace ice on the berries in the morning. But these days the harvest routinely starts earlier. Last year, it began in mid-July, and that was after a late frost had damaged many flowering blueberry plants, drastically reducing the year’s yields. The three years before that had seen drought and heat at levels rarely recorded, requiring growers to invest more in irrigation technology, a major financial expenditure that also depletes precious groundwater. Whereas summers in Down East Maine used to be relatively cool, 80- to 85-degree days are now common, which impacts the quality of the berries and the ability of the harvesters to work. This stresses plants and people alike. And the ideal growing conditions for wild blueberries are moving north from Maine into Canada. Although scientists at the University of Maine are analyzing how berries respond to heat stress and excessive precipitation, in order to help growers predict how probable climate scenarios will impact their blueberries, there are no easy solutions. “If the industry is going to stay here in Maine, there are more steps we need to take to create field tools that help farmers continue farming,” for example automated alerts that warn of a damaging frost, says Lily Calderwood, a wild blueberry specialist at the university.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/ae/d2/aed2e2eb-7a9b-4c5e-bd5b-ad463917fff2/julaug2024_f02_blueberries.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/9a/ab/9aab1fc0-72db-4814-9637-aa674ca92911/julaug2024_f06_blueberries.jpg)

When the harvest is over, the blueberry fields turn bright red as autumn settles in. In the winter, a wind-whipped snow settles on them. It was in this season of dormancy that I spoke with Bailey again over FaceTime. She sat beside her woodstove in her home in Indian Township. She spoke about the sense of community at the barrens she remembered from when she would go as a girl to pick berries every summer with her grandmother. “I go there to make the community that I remember, and to connect with the people the way that I used to,” she said. She runs a store at the blueberry camp, for example, where rakers can buy affordable food on credit, and she organizes meals to ensure that everyone is fed. “People don’t always show up with much money. So I always make sure, when I’m bringing a meal, I’m bringing enough to feed everybody.” She is also keenly aware of the time, not so long ago, when her people were not allowed to celebrate their culture. She now brings her grandchildren to the harvest, where they attend the Blueberry Harvest School during the day and play at the camps at night. “I’m able to create community there,” she said. “Culture isn’t stagnant.”

:focal(2699x1825:2700x1826)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/aa/b5/aab5e142-aae2-45a4-8e16-e3116f21f253/julaug2024_f16_blueberries.jpg)