King of the Mud Dragons

Robert Higgins has spent his career dredging out tiny creatures from dirt and obscurity

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/fd/2e/fd2e9c84-8cff-4c56-a38a-bf1ca62eabcc/mud-dragon-higgins-1200x740.jpg)

This article is from Hakai Magazine, an online publication about science and society in coastal ecosystems. Read more stories like this at hakaimagazine.com.

A serrated rostrum of a sawfish shares wall space with a dozen or so carved wooden masks from Madagascar, Tahiti, Chile, Peru, and beyond. Behind the couch hang four paintings—Chinese landscapes delicately rendered on silk—each depicting a season. On the bookshelf, 80 or so small flags stand at attention, lined up like a miniature United Nations court of flags—one for every country Robert Higgins visited in his lifelong quest for dragons.

Now 85, Higgins’s dragon-hunting days have passed, but the work he pioneered continues—younger searchers are off on modern expeditions. And while the world Higgins traveled was large, the world he studied was not. He spent a lifetime searching for animals smaller than the dot on a 12-point i. His specialty is a group of marine organisms called kinorhynchs, aka mud dragons.

Mud dragons are just one type of meiofauna, animals so diminutive they live between grains of sediment. They swim through the watery film surrounding each grain, or navigate the terrain of sand and mud—veritable mountains to scale—using suction pads, hooks, or tiny toes. Just a handful of marine sediment is a meiofauna metropolis. They’re so numerous that under a single footprint on moist sand there could be up to 100,000 individuals. A brief walk, say just 85 steps, might tromp over eight and a half million organisms, a number equivalent to the population of New York City.

But for a group of animals so plentiful, they are little known and poorly understood, except by a dedicated few. Meiofauna means lesser or smaller animals, and Higgins has spent a lifetime challenging such a dismissive descriptor. Far from being “lesser,” to him this abundance of life speaks of endless opportunity. Higgins’s passion has been to bring these animals the due they deserve, to bring the obscure out of obscurity.

Forget Daenerys Targaryen, mother of dragons, and her quest for the Iron Throne—Robert Higgins was the original. This father of dragons has been building his kingdom since he snagged his first mud dragon over 60 years ago.

Today, Higgins lives in a modest two-bedroom apartment in a retirement community in Asheville, North Carolina. Widowed in 2010 after his beloved wife, Gwen, died of cancer, he shares the space with a fluffy, white Havanese, Susie, who today is tricked out in a pink, ruffled collar. A talented artist, he spends some time oil painting—a recent subject is Echo, his African gray parrot of 30 years—but is still keenly interested in meiofauna research, and signs of his life’s work fill his home.

A balsa wood model of a mud dragon is prominent atop his media cabinet. The model was once on display at the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of Natural History, where Higgins spent 27 years. “They had a terrible model of a kinorhynch,” he says, “so I carved this one.”

About the length of his forearm, Higgins’s model is no delicate tchotchke. Scaled up to about 500 times the actual size of the largest kinorhynch, the model brings to life the 13-segment creature, with its retractable head covered in recurved spines. To move through the sediment, a mud dragon thrusts its head out of its cylinder-like body, hooks its spines on the grains of sediment, and then hauls itself forward. Its mode of locomotion explains the etymology of kinorhynch, Greek for moveable snout.

Nearby, a packed bookcase speaks to Higgins’s fascination with the natural world—several atlases, titles on birds and insects, the textbook Cell Structure and Function. The lower shelves hold two bulging black binders filled with copies of Higgins’s professional publications, all neatly collated in color-coded plastic sleeves. Together, they form a paper trail, documenting a career spent searching for life in the world’s sediments.

Higgins’s travels with meiofauna began in 1952, when he arrived as an undergrad at the University of Colorado Boulder, fresh-faced and buzz cut, newly released from the Marine Corps. In his second year there, he met professor Robert Pennak, who introduced him to the world of invertebrates, including tardigrades, a type of meiofauna so pudgy they’re called moss piglets or water bears.

Pennak hired Higgins for 35 cents an hour to work in the university’s moss and lichen herbarium, where he’d regularly find hundreds of microscopic animals, including water bears, in the moss samples. “If you take a lush piece of moss, put it in a bowl of water and squeeze it … you have about a 50 percent chance of finding a tardigrade,” he says.

Higgins was enamored by the tenacity of tardigrades, with their death-defying adaptions to desiccation, freezing, radiation, and other extreme environmental stresses. So after taking every available course on invertebrates and completing his bachelor’s degree, he went on to do a master’s degree on the life history of a tardigrade species living in the mosses of the Boulder region.

He thought about staying at Boulder for a PhD on water bears, but Pennak encouraged his protégé to go elsewhere, and also delivered some prophetic advice. “He said, ‘Do something no one else has done, and then you make your own science,’” recalls Higgins. “I was quite affected by that.”

Higgins applied to five universities, was accepted to five, and chose Duke University in North Carolina. But between leaving the Colorado mountains and arriving on Duke’s Atlantic shore, Higgins made a trip to the Pacific for a summer fellowship at the University of Washington’s Friday Harbor marine laboratory. Before he left, Pennak asked Higgins to try to collect a few samples he was lacking in his teaching collection, including kinorhynchs.

Even though he’d never seen a kinorhynch, Higgins accepted the mission. Within days of arriving, he was on a boat dredging sediment from the seafloor. Back in the lab, he was confronted with a bucket of mud and water and the tactical problem of trying to extract minute creatures from the crud. “Self, how the heck am I going to go through all this mud?” Higgins recalls of the moment.

The only information he had on technique was from the one scientist who had previously found a few kinorhynchs at Friday Harbor. Squeezing a pipette, she’d added bubbles one by one to the sample, relying on the physics of bubbles to find the animals. The exoskeletons of kinorhynchs and other hard-bodied meiofauna are hydrophobic—they repel water—causing them to stick on the bubbles in the surface film.

Higgins tried the method, picking the speck-sized animals off the water surface using a small tool with a tiny wire loop at one end, but it was tedious work. After an hour, he’d managed to snag just four; his days of squeezing dozens of tardigrades out of Colorado moss seemed halcyon in retrospect. But, just as a weak batch of adhesive gave 3M its Post-it note, a fumble in the lab that day proved serendipitous, perhaps not for the world, but at least for those trying to separate infuriatingly small creatures from a slurry of sand and water.

Higgins accidentally dropped a piece of paper into the water and when he pulled it out, it was covered in specks. He washed the sample into a petri dish and took a look under the scope—kinorhynchs were everywhere. The low-tech, highly effective technique, “bubble and blot,” was born. And so was Higgins’s life’s work.

The senior researchers at Friday Harbor were astounded when Higgins showed them the wealth of kinorhynchs he’d managed to find, and after working on the samples for his summer term’s research paper—and finding a paucity of literature on kinorhynchs—Pennak’s advice was staring him in the face. He’d found his “something” that few people knew anything about.

**********

Back at Duke in the fall, with his Friday Harbor kinorhynch collection in tow, Higgins informed his PhD supervisor that he was switching from moss piglets to mud dragons. His adviser admitted he wouldn’t be much help—he knew next to nothing about kinorhynchs—but provided what support he could. “He bought me the equipment I needed and turned me loose,” says Higgins.

Higgins worked through the hundreds of mud dragons he’d collected, painstakingly detailing the morphological minutiae of spines and scalids, oral styles and cuticular hairs. The seven species he’d found were undescribed, which left the meticulous work of scientific description up to him. “Doing my thesis on the life history of kinorhynchs got me started,” he says, “and that got me everything.”

He became an expert in kinorhynchs, and quickly became the go-to taxonomist for that phylum as well as many other groups of meiofauna. Soon researchers from around the world leaned on his skills, shipping all manner of unidentified animals his way. “Send them to Bob, he works on these weird things,” Higgins later recounted in a speech.

But Higgins didn’t want to remain the only guy who works on weird things. As he progressed in his career from Duke to Wake Forest University and finally to the National Museum of Natural History, where he served as curator in the department of invertebrate zoology, he nurtured a community of researchers who collectively animated the hidden micro-kingdoms below our feet.

In 1966, he cofounded the International Association of Meiobenthologists and launched its newsletter, with an eye to keeping the communication, both professional and personal, flowing. Three years later, while working for the Smithsonian in Tunis, Tunisia, he co-convened the first International Conference on Meiofauna. Twenty-eight participants from seven countries attended. It was a start.

**********

Almost 50 years after Higgins first snagged some mud dragons on a sheet of paper, María Herranz, a kinorhynch biologist doing a postdoc at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver, is bubbling and blotting the sediment sample she collected that morning near the Hakai Institute’s Calvert Island Ecological Observatory on British Columbia’s central coast. As she works, she recounts the story of how Higgins discovered the technique—with slight tweaks as one expects in an as-told-to story (her version had Higgins with a cold, and a tissue in his shirt pocket falling into the sample). The details of paper versus tissue don’t matter so much, but what is clear is the legacy that has come down via the generations from when Higgins was pretty much on his own studying kinorhynchs, and today, when the international kinorhynchologist club has grown to about 10.

A kinorhynch moves by everting its spine-covered head, hooking the spines on a sediment grain, and pulling its body forward. Video by María Herranz

Out sampling, Herranz uses a dredge, modeled after one designed by Higgins, to grab the top layer of mud . (“The first five to 10 centimeters is where the action is,” explains Higgins, “that’s where it’s still oxygenated.”) All the other dredges he’d tried dug too deep, so Higgins designed one. Rather than patent it, and hold the idea close, he readily shared the plans with any researchers who asked so they could build their own.

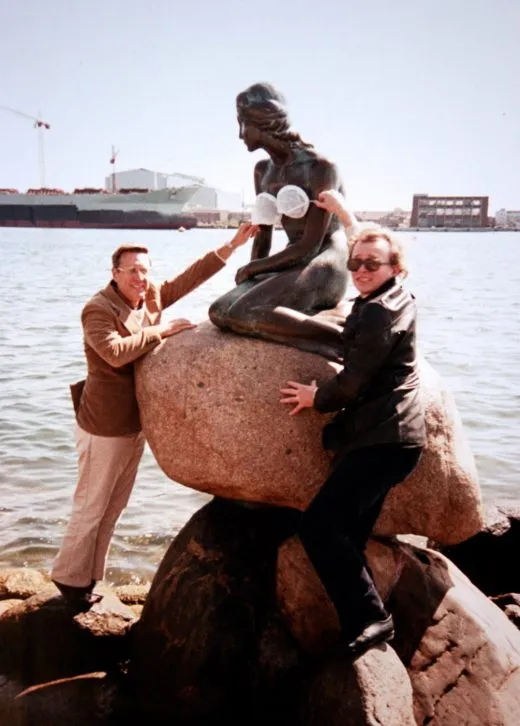

When she’s ready to strain the creatures she’s blotted from the mud slurry, Herranz uses a small net (think butterfly net meets coffee filter). It’s another Higgins-designed piece of equipment used by kinorhynch researchers, and each one was sewn by his wife, Gwen. The net’s resemblance to a bra cup—a pointy vintage number—was not lost on a crewman on one of Higgins’s research expeditions who saucily held the net to his chest. The name “mermaid bra” stuck and regularly makes its way into the methodology section of scientific papers. During her lifetime, Gwen made nets for anyone who asked and they all came with a label and serial number. Herranz’s reads: Gwen-Made Ltd., Mermaid Bra, SN 070703. (To recognize Gwen’s contribution to the science, Herranz named a new species of kinorhynch after her: Antygomonas gwenae.)

Herranz has never met Higgins, but his name comes up often in her kinorhynch work. There’s bubble and blot, the dredge, the mermaid bra, the meiofauna bible—Introduction to the Study of Meiofauna—he coauthored, but most importantly there is lineage. Higgins and Herranz are linked by Fernando Pardos, a zoologist at Complutense University of Madrid, who encouraged Herranz to study kinorhynchs instead of jellyfish, a suggestion strikingly similar to the encouragement Higgins once gave him.

In 1986, fresh from completing his PhD, Pardos, then 30, was applying for a university teaching position. In preparation for the interview, and anticipating he’d be asked to teach invertebrate zoology, he was searching for information on a newly described group of meiofauna. Pardos knew Higgins had been involved with the discovery, so he wrote him a letter asking for information.

“To my surprise, Bob Higgins answered with a stack of scientific papers and a letter,” says Pardos. In the chatty letter, Higgins noted that his specialty was phylum Kinorhyncha and added a sentence that would send any ready-to-launch zoologist’s heart aflutter: “Did you know there is nobody studying [kinorhynchs] in Spain?”

Just as Pennak had encouraged Higgins to study something that no one else was, Higgins was offering the opportunity of a lifetime to Pardos. And it came with room and board. In his letter, Higgins invited Pardos to stay with him and Gwen in Washington, DC, despite never having met the young student. “These are the kind of things that happen maybe once in your life,” says Pardos. “My only English was, ‘My tailor is rich,’ but I traveled to the States and I found there the most generous people, both in personal terms and in scientific terms.”

Pardos and Higgins spent two weeks together in the summer of 1989, one in Washington at the National Museum of Natural History, and one at the Smithsonian’s field station in Fort Pierce, Florida.

“Bob opened my eyes to the meiofauna world,” says Pardos. “He was so enthusiastic and could transmit the excitement of seeing something that very few zoologists have seen.” He recalls a quiet moment in the lab when they were both at the microscope looking through samples, when Higgins cried out, “Kiiiiiiiiii-no-rhynch!” “This may have been his 100,000th kinorhynch, but he looked as excited as the first time,” says Pardos, adding that when he found his very first mud dragon, Higgins took him out for a beer. “It was the first time I’d seen a kinorhynch alive and I thought, ‘This is fascinating.’ I am still fascinated.”

From that initial time together, Pardos and Higgins forged a strong bond that persists to this day. The summer after Pardos’s stint in the United States, the pair met on the north coast of Spain where they collected and described the first two species of Spanish mud dragons. Their collaborations continued until Higgins’s retirement, but they still have long chats on the phone every few months during which Pardos passes on research updates. “He is absolutely curious about my work and he’s very proud,” says Pardos.

With Pardos and other colleagues from the meiofauna nexus, Higgins traveled the world collecting wherever he could, taking along a portable dredge—the “mini-meio”—in his impeccably packed luggage. No meiofauna anywhere was safe from his shovel and sieve. Higgins was encouraged by the Smithsonian to describe and collect what he could, snagging life from marine sediments, piecing together a picture of life in the mysterious muck animal by animal. His work created an international repository of meiofaunal life, an essential time capsule given that coastal habitats are dredged and polluted with astonishing speed.

And the collection is still a meiofauna mother lode for contemporary researchers. “There is more than one scientific life of work waiting there,” says Pardos, who regularly sends students to the Smithsonian for research, scouring Higgins’s collection of prepared microscope slides and tiny vials with their impeccably lettered labels.

In a world with macroscopic spectacles such as Komodo dragons, sea dragons, snapdragons, and dragonflies, it might seem like the epitome of obscure pursuits to geek out on row after row of jars and slides and lipstick-sized vials housing microscopic mud dragons and other species from this nanosized wonderland. But as with many scientific pursuits, you never know where a serendipitous sample causes a life to zig when it might have zagged.

Higgins recognizes that serendipity—“my old friend” as he once called it—is a central character in his life story: a sheet of paper falls into a bucket, a letter from Spain crosses a desk, an almost-missed train leads to the discovery of an entirely new life form.

**********

Years before Pardos received his life-changing letter from Higgins, another meiofauna researcher, Reinhardt Kristensen, was sampling the sediment near the Roscoff Marine Station on the coast of Brittany, France. It was his last day in the field and he was racing against the train schedule. Kristensen, then a senior lecturer at the University of Copenhagen and a colleague of Higgins’s through the meiofauna network, was processing a large sample, preserving it for future study. The protocol for separating the meiofauna from its sediment is multistep, but Kristensen didn’t have time, so instead he quickly rinsed the sample with fresh water. The temporary salt imbalance shocked the creatures within, causing them to loosen their grips on the sediment. He strained them into a vial, and was off to catch the evening train to Copenhagen.

Several months later, in the fall of 1982, newly arrived at the Smithsonian Institution to do a postdoc in Higgins’s lab, he showed his colleague one of the unfamiliar animals he’d collected that day near Roscoff. It looked familiar to Higgins. “I went over to the cupboard and pulled out a little vial and dumped it into a petri dish. They were the same things, or species of the same things,” Higgins says.

Eight years before, Higgins had found a single specimen of this type of animal among thousands of meiofauna collected on a six-day expedition off the North Carolina coast. From the moment he looked at it under the scope, Higgins knew he had something special on his hands, but with only one specimen, there was little he could do but preserve it and file it in his collection. “Every once in a while, I’d take it out of the cabinet to take a look,” he says.

When you’re working with poorly studied yet ubiquitous animals, finding organisms new to science is not uncommon. (As Pardos notes, “Every time I look at a sample, I see more things that I don’t know than things I do.”) But while finding a new species may be almost routine, the higher up you move on the classification ladder, through class, order, family, and such, finding new animals that deserve an entirely new grouping is increasingly implausible. And discovering an organism different enough to warrant its own phylum comes only to a rare few. After all, all known animal life on Earth—to date almost one million species and counting—is categorized into one of only 35 phyla.

And a new phylum is just what Higgins and Kristensen had on the lab table before them.

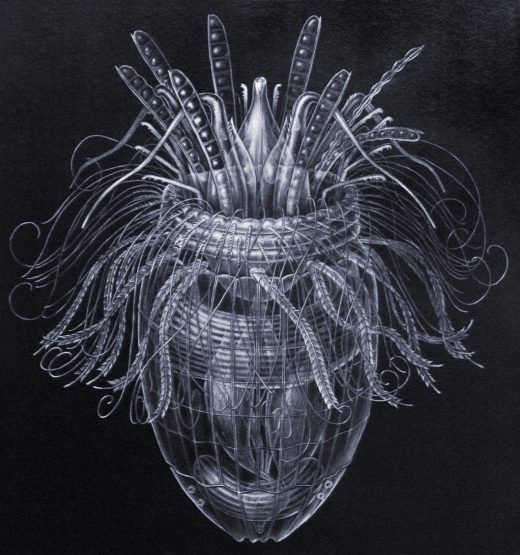

An ocean apart, the two men had discovered two species of a new kind of animal. Higgins had found an adult of one species in 1974, and Kristensen found the full life cycle—adult and larval stages—of another species in 1982. Using the Latin words loricus (corset) and fero (to bear), they called the phylum Loricifera, the “girdle wearer,” to reflect the corset-like rings making up the animal’s armored cuticle.

After painstakingly detailing the original specimen for their proposed new phyla, Kristensen, now curator at the Natural History Museum of Denmark, made the announcement of their discovery with details of Nanaloricus mysticus, the “mysterious girdle wearer,” to the world in a 1983 paper. Loricifera was one of only four new phyla described in the 20th century.

In honor of his colleague’s contribution, Kristensen named the loriciferan’s larval stage the Higgins larva. “That was my payoff and a wonderful one,” says Higgins.

**********

Beside the balsa wood kinorhynch on Higgins’s media cabinet, sits another sculpture—this one a 3D computer-generated glass model of Pliciloricus enigmaticus, the loriciferan Higgins found off the North Carolina coast. The art piece, which renders the animal in delicate bubbles, was made by Kristensen and created in celebration of the 20th anniversary of the publication of the new phylum Loricifera.

Kristensen and Higgins continued to work together throughout the rest of Higgins’s career, in the United States and around the world, discovering and naming many new species, including a loriciferan they named for Gwen Higgins—Nanaloricus gwenae. As with Fernando Pardos, Higgins was a professional colleague, a mentor, and a generous personal friend to Kristensen and his family. At times, Higgins, who is 16 years older, offered some life skills to help the young scientist launch his career. He gave him pointers on delivering scientific talks for instance, and even instructions on how to tie a tie. “You can’t go to meet a president without a proper knot,” says Kristensen. It was a life skill that came in handy as the men were recognized for their discovery in several ceremonies, including one at the Smithsonian hosted by then-US vice president George H. W. Bush, and another in Denmark where they were honored by Queen Margrethe II.

But for all of the accolades—the times his colleagues have added higginsi to a newly discovered animal; the hundreds of scientific papers with Robert Higgins as contributing author; and even to his part in discovering a new phylum of animals—it is the work that Higgins has done to build networks, foster relationships, and share generously that is, perhaps, his greatest legacy.

At its core, at its purest non-cynical, non-competitive center, science is about sharing. Through journals, researchers share their discoveries; at conferences, they speak a common language with their peers, reveling in the knowledge that, for a few days at least, they’re not the only wonk in the room; in the field, they slog through the mud and haul nets, and share a beer at the end of a hard day. And, just as for Higgins’s prized meiofauna, where a magnificent world unfolds in the interstitial spaces between the grains of sand, for scientists it is often in the interstices between all the formalities—a chance comment over coffee, a tossed out phrase in a presentation, a brief mention of something observed or collected or pondered—where the wonder happens.

Related Stories from Hakai Magazine: