Lost at Sea

What’s killing the great Atlantic salmon?

Last September on Newfoundland's Humber River, writer Michael Parfit set out in search of the king of sportfish, the Atlantic salmon. What he found instead was a mystery.

With a historical domain stretching from the Connecticut River all the way to Portugal, Atlantic salmon were the monarchs of the sea—so numerous they were once used as fertilizer. But pollution and heavy commercial fishing in the 20th century took their toll. Salmon enjoyed a brief rebound after buyouts of commercial fisheries and the introduction of aquaculture. But in the 1990s, numbers of Atlantic salmon returning to their home rivers drastically declined, and no one knows why.

Complicating the mystery is the salmon's complex life cycle. Spawned in rivers, they migrate across thousands of miles of ocean to live part of their adult lives, then come home to their natal rivers to spawn. Unlike Pacific salmon, however, they don't die after spawning, but return to the ocean. At every point in this odyssey, they are vulnerable to habitat change and predators, which is why there are currently more than 60 hypotheses to explain their demise.

One of the suspects is aquaculture, as farmed fish can escape and mix with wild salmon, spreading disease. Another is increasing numbers of poachers as well as predators, such as seals and cormorants. And yet another is habitat disruption, from disturbances to spawning beds to declining numbers of salmon prey in the ocean. Better research, including accurate tracking of the fish at sea, is one key to solving the mystery.

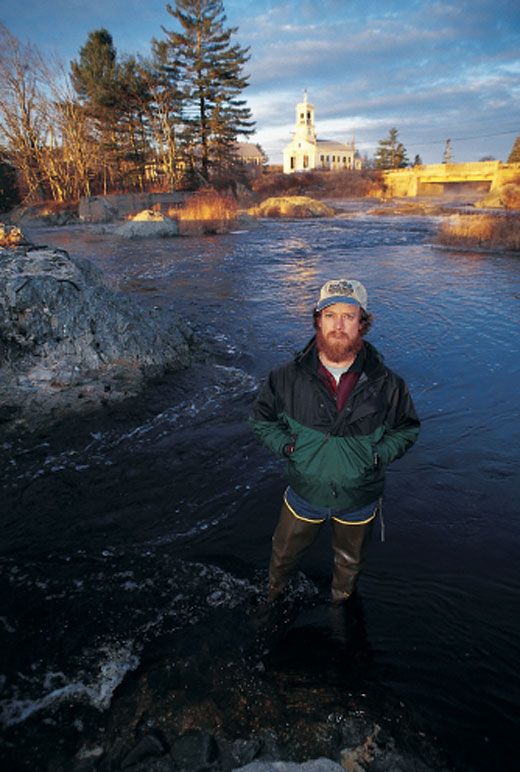

Yet, even with declining numbers, the fish continue to be a major attraction. When salmon advocate Bill Taylor catches one, he holds his hand against the fish's belly, where he can feel its heart beat strong and fast against his fingers. Then he lets it go. "You realize this fish has come all the way from Greenland," he says. "It almost makes you get a lump in your throat." Defying seals, poachers, pollution and habitat disruptions—indeed, everything a rapidly changing world has thrown at it—this miraculous fish still comes home.