Luna: A Whale to Watch

The true story of a lonely orca leaps from printed page to silver screen, with a boost from new technology

What if you found a story right in front of you, and it had the best real-life hero you’d ever met and a story line you could never have imagined on your own? What if it filled you with amazement and joy and sadness and hope? What if you could not resist telling everyone you met until someone said it ought to be a movie because the studios are just remaking superhero movies these days and need something fresh, and you thought, yes, that’s right?

And what if the studios weren’t interested, and you took advantage of a technological revolution and set out to make the movie yourself? Then what if, against all odds, you finished your movie and people liked it but the theaters had no interest? And what if an honest-to-goodness movie superhero came along with a green flash at the last minute to save the day?

A likely story, you think. But it happened just that way (except for the green flash) to my wife, Suzanne Chisholm, and me. It began right here in the pages of this magazine, and you should be able to see the result in theaters this summer.

People have always been driven to tell stories. But until recently, most people with stories clamoring to get out of their heads have not had access to the world’s most powerful narrative medium: movies. Moviemaking has been the almost exclusive dominion of large organizations usually driven more by profit than by stories.

But that’s changing, and there is hope right now that the technological revolution now underway may help revive a medium that even some Hollywood executives admit is growing stale.

The story that captured us was about a young killer whale, an orca. People called him Luna. Because orcas are highly social animals and Luna had found himself alone, cut off from his pod, he seemed to think he could make a life among humans. So he tried to make contact with people at docks and boats along a fjord called Nootka Sound, on the west coast of Canada’s Vancouver Island.

I had written for Smithsonian for years, and the editors assigned me to write about this unusual cetacean character. Luna, whom the press called “the lonely orca,” had become the subject of controversy in both public and scientific arenas over what should be done with him—whether to catch him, befriend him or force people to stay away from him. A political clash over Luna’s fate between the Canadian government and a band of Native Americans was the official focus of my article. But Luna took over the story the way a great actor steals a scene.

At the time the article was published, in November 2004, no one knew what was going to happen to Luna. His apparent longing for contact brought him near dangerous propellers and a few cranky fishermen, who began to threaten to shoot him, and no one had a solution. The last lines of the article expressed our worry:

Natives or not, in the past centuries we have all built distance between ourselves and the rest of life. Now the great wild world never glances our way. But when an animal like Luna breaks through and looks us in the eye, we cannot breathe.

And so we become desperate to keep these wild beings alive.

The article generated interest in doing a movie. People called and came to visit, but nothing came of it.

We talked to people who made documentaries. They told us that the story was nice, but if it didn’t have a strong point of view, they weren’t interested. There had to be advocacy.

We tried the studios. We wrote proposals and took a trip to Hollywood.

“Sure,” said one studio executive, “but your whale is one of those big black and white things. What about those other ones, the little white whales, what do you call them, belugas? Aren’t they cuter? Could we do it with a beluga?”

But while this was going on, things were happening in the way movies are made. In the mid-’90s, the price of high-quality digital video cameras came down dramatically. The cameras were simple to operate, and within a few years they were shooting high-definition footage that looked great on the big screen. With editing software that could be installed on a laptop, they enabled moviemaking at a fraction of the previous cost.

In 1996, the Sundance Film Festival, the most prominent independent film festival in the world, had some 1,900 submissions, including 750 feature films, and people thought that was a lot. But this year Sundance had 10,279 entries, including 3,812 feature-length films. Most of them were filmed with digital cameras.

“The opportunity to be a filmmaker is definitely becoming more democratic,” David Courier, a programmer at Sundance, told me. “People who couldn’t afford to make a film in years past are feeling empowered.”

One of the newly empowered filmmakers is a documentarian named James Longley, who trained on 35-millimeter film. “I certainly miss the dynamic range of film negative and the mysterious wonderfulness of getting material back from the lab, days later, smelling of chemicals,” Longley told me in an e-mail. But “I can’t say I miss the bulk of the cameras or the expense of working on film at all, not for the kind of work that I do.”

Longley made Iraq in Fragments, a documentary that played in U.S. theaters for almost a year in 2006 and 2007. He spent two years making it in and out of Iraq after the U.S. invasion, working with only a translator, filming with small digital cameras and editing with two colleagues on home computers. After it was released, a Village Voice critic wrote, “[I]f Longley’s astonishing feat of poetic agitation has a precedent in the entire history of documentary, I’m not aware of it.” The movie was nominated for an Oscar for Best Documentary Feature in 2007.

“I could never work the way I do now if the world were still analog,” Longley told me. “It would be a practical impossibility.”

For Suzanne and me, too, it would have been impossible to make our movie without the new digital tools, though unlike Longley, who planned his Iraq film in great detail, we had no idea in the beginning that we were even shooting a movie.

At first we used a couple of little cameras the same way we might use a notebook or a tape recorder—to store information for the article. But when the events that we wrote about in Smithsonian appeared in our lenses, we started to think that the digital tapes we had just been tossing in a drawer might be important.

Like Longley, we spent far more time on our story than we ever expected. The low cost of equipment allowed us to stay on Nootka Sound and spend the time seeing things that a rush job would never have allowed.

Slowly we learned the patterns of Luna’s life—where he would go; the boats and people he seemed to like best; the many ways he tried to communicate, from whistles and squeaks to imitations of boat motors to slapping the water and looking in people’s eyes; and how he would often roll on his back and wave one pectoral flipper in the air for no reason we could detect.

Once, we were motoring around a point of land in our ancient inflatable boat, wondering where Luna was. We came upon a barge anchored near the shore that seemed to have an out-of-control fire hose squirting water straight up into the air like a fountain gone berserk.

When we got closer we discovered that the crew had turned the fire hose on in the water, where it lashed around like a huge spitting serpent. But it was under control—Luna’s. There he was, repeatedly coming up out of the depths to catch the thrashing hose in his mouth near its nozzle. He was making the fountain himself, waving the plume of water around, spraying us and the guys on the barge, all of us soaked and laughing.

Without the freedom of time given by the low cost of equipment, we would not even have been there to see the Luna fountain. Not only that, but on a similar occasion, when Luna tossed a load of water right on our unprotected camera with his tail, the low cost saved us—we could afford a replacement.

Months passed. Then a year. I broke away from Nootka Sound for a few weeks to do a couple of magazine stories to pay the bills. Eventually, as threats to Luna grew from a few disgruntled fishermen who had their sport interrupted by his attentions, we spent more and more time on the water trying to keep him away from trouble, filming when we could.

Finally an editor who commissions projects at the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation saw some of our clips and gave us financial support to do a 42-minute television show for the CBC’s cable news channel. We were delighted. By then it had been nearly two years since we had agreed to do the magazine story. We had 350 hours of footage.

And then one morning we got a call we could not bear to believe. Luna had been killed by a tugboat propeller. Vancouver Island’s biggest paper, the Victoria Times-Colonist, published several photographs and some fine articles that said farewell.

But to us that wasn’t enough. Luna’s life deserved more than fading newsprint. We were starting a book and were working on that 42-minute TV show, but we began to believe that Luna’s life had a grandeur and beauty that seemed bigger than all those things combined. When our CBC editor saw the first 40 minutes, he said he thought it should be longer, and we began to talk about a full-length movie. But who would do it? The studios had said no. It would be nobody—or it would be us. Yes! we said, trying to persuade ourselves. Finally, with our editor’s encouragement, we decided to make a full-length, nonfiction feature movie.

It has now been over five years since I first sat down at the computer and started editing. Things have not been easy. The obstacles between a digital camera and a theatrical screen are still many and high, and there’s more excellent competition every day.

We called the film Saving Luna. My son, David, and a composer colleague wrote the music—again using new technology to manage live performances. We sent the film to festivals and held our breath. We got in—to some. Not Sundance, but Santa Barbara. Not Tribeca, but Abu Dhabi. Not Berlin, but Bristol. And yet the biggest of doors—to U.S. theaters—remained closed. Our film joined a category that studios and distributors tend to call, sometimes with disdain, “festival films,” as if only cinephiles can enjoy them.

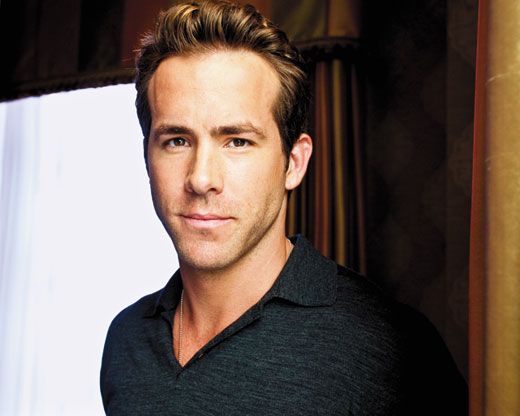

And then out of the blue, diving through the sky with a roar and a smile and a flash of green light, came our very own superhero: Ryan Reynolds, last year’s People magazine Sexiest Man Alive and star of this year’s Green Lantern, one of the most anticipated superhero movies of the summer. Ryan had grown up in Vancouver, not far from the waters in which Luna’s family still roamed. He had heard about the film through our agent and he loved it.

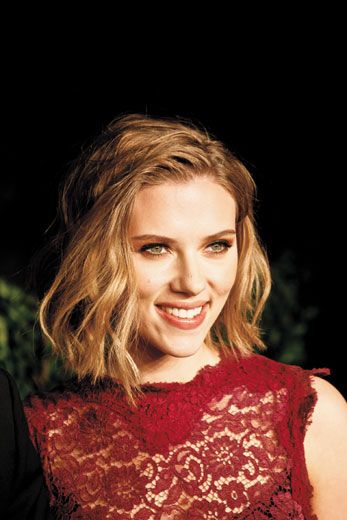

He gave a copy to Scarlett Johansson, the actress, and the two of them became executive producers. Ryan took over the narration, which he did with his characteristic dry humor and easygoing delivery, adding funny asides as we went along. Then both of them worked with us to make a new film out of pieces of the old one and new footage we shot. It’s called The Whale.

This was another advantage of the new technology: we could just crank up the home computer and begin again. We worked on the film for another year. And at last that combination of homegrown story and Hollywood star power opened the final doors. The Whale, and Luna, are finally about to reach the big screen. It has been an amazing journey, made possible by technology. And what does it symbolize?

“I certainly don’t want to go on record as saying the studio system is going to die, not in my lifetime,” David Courier told me with a laugh. “Huge special-effects-driven films and big Hollywood glamour are going to be around for a good while, because people often go to the movies as an escape. But then there are other people who go to movies just to see a good story. Independent cinema is providing a lot of the good stories.”

It is at least a partial shift in creative power. When the hard-boiled novelist Raymond Chandler went to Hollywood in the 1940s, he watched in frustration as studio executives demoralized the storytellers.

“That which is born in loneliness and from the heart,” Chandler wrote, “cannot be defended against the judgment of a committee of sycophants.”

So the irony is this: technology is freeing us from technology. The machines that once gave money veto power over originality are becoming obsolete, and freedom grows. Now, a story may rise more easily to our attention simply because it is stirring. People can follow their passions into the smoke of a shattered nation, as James Longley did, or into the life of a whale, or into the endless wild landscape of the imagination, and bring what they find back in their own hands.

And in the end the technology is just a tool. When Suzanne and I sit in the back of a theater behind the silhouetted heads of strangers, and feel through their stillness and laughter that they are getting to know a friend who was a gift from the blue, we never think about the equipment that made it all possible. As it should be with the things we humans are compelled to make—those tools work best that work in the service of life.

Michael Parfit has written for Smithsonian and other magazines since the 1980s.