Mad About Seashells

Collectors have long prized mollusks for their beautiful exteriors, but for scientists, it’s what inside that matters

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/conus-gloriamaris-shell-631.jpg)

When Phil Quinton got rolled under a log at a California sawmill some years ago, he crawled out and went back to work. It turned out that he had a crushed spine. After an operation the pain just got worse, Quinton says, and he learned to self-medicate with drugs and alcohol. Eventually, his doctors put him on massive doses of morphine until he could no longer stand the side effects.

Then a doctor told him about cone snails—a group of marine snails, beautiful but deadly—and a new drug, a synthetic derivative from the venom of one of them, Conus magus, the magician's cone. Quinton had actually seen cone snails kill fish in an aquarium and on television, and it was a kind of magic, given that snails move at a snail's pace and generally cannot swim. "It took 20 minutes," he says, "but the snail came over to the fish and put out this long skinny thing and touched it, and that fish just froze."

The snail's proboscis was a hypodermic needle for its venom, a complex cocktail of up to 200 peptides. Quinton also knew that cone snails have at times killed people. But for the drug, called Prialt, researchers synthesized a single venom peptide that functions as a calcium-channel blocker, bottling up pain by interfering with signals between nerve cells in the spinal cord. The third day after he started taking Prialt, says Quinton, now 60, the pain in his legs went away. It wasn't a miracle cure; he still had back pain. But for the first time in years, he could go out for a daily walk. He owed his recovery to one of the most underrated pastimes in human history: shell collecting.

The peculiar human passion for the exoskeletons of mollusks has been around since early humans first started picking up pretty objects. Shellfish were, of course, already familiar as food: some scientists argue that clams, mussels, snails and the like were critical to the brain development that made us human in the first place. But people also soon noticed their delicately sculpted and decorated shells. Anthropologists have identified beads made from shells in North Africa and Israel at least 100,000 years ago as among the earliest known evidence of modern human culture.

Since then various societies have used shells not just as ornaments, but also as blades and scrapers, oil lamps, currency, cooking utensils, boat bailers, musical instruments and buttons, among other things. Marine snails were the source of the precious purple dye, painstakingly collected one drop at a time, that became the symbolic color of royalty. Shells may also have served as models for the volute on the capital of the Ionic column in classical Greece and for Leonardo da Vinci's design for a spiral staircase in a French chateau. In fact, shells inspired an entire French art movement: Rococo, a word blending the French rocaille, referring to the practice of covering walls with shells and rocks, and the Italian barocco, or Baroque. Its architects and designers favored shell-like curves and other intricate motifs.

The craving for shells was even powerful enough to change the fate of a continent: at the start of the 19th century, when rival French and British expeditions set out for the unknown coasts of Australia, the British moved faster. The French were delayed, one of those on board complained, because their captain was more eager "to discover a new mollusk than a new landmass." And when the two expeditions met up in 1802 at what is now Encounter Bay, on the south coast of Australia, a French officer complained to the British captain that "if we had not been kept so long picking up shells and catching butterflies...you would not have discovered the south coast before us." The French went home with their specimens, while the British quickly moved to expand their colony on the island continent.

The madness for shells that took hold of European collectors from the 17th century onward was largely a byproduct of colonial trade and exploration. Along with spices and other merchandise, ships of the Dutch East India Company brought back spectacularly beautiful shells from what is now Indonesia, and they became prized items in the private museums of the rich and royal. "Conchylomania," from the Latin concha, for cockle or mussel, soon rivaled the Dutch madness for collecting tulip bulbs, and often afflicted the same people. One Amsterdam collector, who died in 1644, had enough tulips to fill a 38-page inventory, according to Tulipmania, a recent history by Anne Goldgar. But he also had 2,389 shells, and considered them so precious that, a few days before his death, he had them put away in a chest with three separate locks. The three executors of his estate each got a single key, so they could show the collection to potential buyers only when all three of them were present. Dutch writer Roemer Visscher mocked both tulip maniacs and "shell-lunatics." Shells on the beach that used to be playthings for children now had the price of jewels, he said. "It is bizarre what a madman spends his money on."

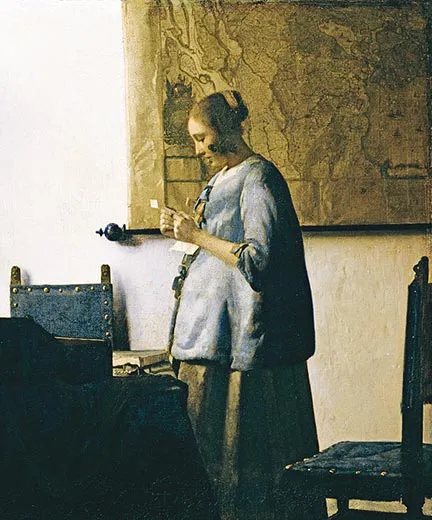

And he was right: at one 18th-century auction in Amsterdam, some shells sold for more than paintings by Jan Steen and Frans Hals, and only slightly less than Vermeer's now-priceless Woman in Blue Reading a Letter. The collection also included a Conus gloriamaris shell, for which the owner had paid about three times what his estate was getting for the Vermeer.

From a financial perspective, valuing shells over Dutch masters may rank among the dumbest purchases ever. There are only 30-some known Vermeer paintings on earth. But the scarcity that could make a shell seem so precious was almost always illusory. For instance, C. gloriamaris, a four-inch-long cone covered in a delicate fretwork of gold and black lines, was for centuries among the most coveted species in the world, known from only a few dozen specimens. One shell-trade story held that a wealthy collector who already owned a specimen managed to buy another at auction and, in the interest of scarcity, promptly crushed it underfoot. To maintain prices, collectors also spread the rumor that an earthquake had destroyed the species' habitat in the Philippines and rendered it extinct. Then in 1970, divers discovered the mother lode in the Pacific, north of Guadalcanal Island, and the value of C. gloriamaris plummeted. Today you can buy one for roughly the price of dinner for two at a nice restaurant. And paintings by Vermeer? The last time one came on the market, in 2004, it went for $30 million. (And it was a minor and slightly questionable one at that.)

But what seems common to us could seem breathtakingly rare to early collectors, and vice versa. Daniel Margocsy, a historian of science at Northwestern University, points out that Dutch artists produced five million or more paintings in the 17th century. Even Vermeers and Rembrandts could get lost in the glut, or lose value as fashions shifted. Beautiful shells from outside Europe, on the other hand, had to be collected or acquired by trade in distant countries, often at considerable risk, then transported long distances home on crowded ships, which had an alarming tendency to sink or go up in flames en route.

The shells that got through to Europe in the early years were mostly sold privately by sailors and civil administrators in the colonial trade. When Capt. James Cook returned from his second round-the-world voyage in 1775, for instance, a gunner's mate aboard the Resolution wrote offering shells to Sir Joseph Banks, who had served as naturalist for Cook's first circumnavigation a few years earlier.

"Begging pardon for my Boldness," the note began, in a tone of forelock-tugging class deference. "I take this opportunity for acquainting your Honour of our arrival. After a long and tedious Voyage...from many strange Isles I have procured your Honour a few curiosities as good as could be expected from a person of my capacity. Together with a small assortment of shells. Such as was esteem'd by pretended Judges of Shells." (The last line was a sly jibe at the lesser naturalists who had taken Banks' place on the second circumnavigation.) Dealers sometimes waited at the docks to vie for new shells from returning ships.

For many collectors of that era, shells were not just rare, but literally a gift from God. Such natural wonders "declare the skilful hand from which they come" and reveal "the excellent artisan of the Universe," wrote one 18th-century French connoisseur. The precious wentletrap, a pale white spiral enclosed by slender vertical ribs, proved to another collector that only God could have created such a "work of art."

Such declarations of faith enabled the wealthy to present their lavish collections as a way of glorifying God rather than themselves, writes British historian Emma Spary. The idea of gathering shells on the beach also conferred spiritual status (although few wealthy collectors actually did so themselves). It symbolized escape from the workaday world to recover a sense of spiritual repose, a tradition invoked by luminaries from Cicero to Newton.

In addition, many shells suggested the metaphor of climbing a spiral staircase and, with each step, coming closer to inner knowledge and to God. The departure of the animal from its shell also came to represent the passage of the human soul into eternal life. The nautilus, for instance, grows in a spiral, chamber upon chamber, each larger than the one before. Oliver Wendell Holmes made it the basis for one of the most popular poems of the 19th century, "The Chambered Nautilus": Build thee more stately mansions, O my soul, / As the swift seasons roll! /... Till thou at length art free, / Leaving thine outgrown shell by life's unresting sea!

Oddly, collectors didn't much care about the animals that actually built the shells. Holmes, for instance, unwittingly blended the characteristics of two separate nautilus species in his poem, according to shell historian Tucker Abbott: "It was as if he had written a poem about a graceful antelope who had the back half of a leopard and the habit of flying over the arctic ice." Collectors often cared passionately about new species, but mainly for the status of possessing something strange and unusual from a distant land, preferably before anybody else.

The absence of flesh-and-blood animals actually made shells more appealing, for a highly practical reason. Early collectors of birds, fish and other wildlife had to take elaborate and sometimes gruesome measures to preserve their precious specimens. (A typical set of instructions to bird collectors included the admonition to "open the Bill, take out the Tongue and with a sharp Instrument pierce through the roof of the Mouth to the Brain.") But those specimens inevitably succumbed to insects and decay anyway, or the beautiful colors faded to mere memory.

Shells endured, more like jewels than living things. In the 1840s, a British magazine recommended that shell collecting was "peculiarly suited to ladies" because "there is no cruelty in the pursuit" and the shells are "so brightly clean, so ornamental to a boudoir." Or at least it seemed that way, because dealers and field collectors often went to great lengths to remove any trace of a shell's former inhabitant.

In fact, however, the animals that build shells have turned out to be far more interesting than collectors ever supposed. One day at the Smithsonian's National Museum of Natural History, which owns the world's largest shell collection, research zoologist Jerry Harasewych was cutting open a small land snail shell from the Bahamas. For scientific purposes, the museum preserves shells in as close to their natural state as possible. These specimens had been stored in the collection four years earlier. But Harasewych suddenly noticed something moving inside. It reminded him of an apocryphal story about a museum where the air conditioning quit and snails, resurrected by the humidity, came oozing out of the collection drawers. He put some of the other dried snails in water, he said, and they too started moving. It turned out that these snails live on dunes in sparse vegetation. "When it starts to get hot and dry, they seal themselves up within their shells," he said. "Then when the spring rains come, they revive."

Among other surprising behaviors, said Harasewych, a muricid snail can climb aboard an oyster, drill through its shell, then insert its proboscis and use the teeth at the tip to rasp up the oyster's flesh. Another species dines on shark: the Cooper's nutmeg snail works its way up through the sand underneath angel sharks resting on the bottom in the waters off California. Then it threads its proboscis into a vein in the gills and sucks the shark's blood. For the shark, it's like a gooey mosquito bite.

The eat-or-be-eaten dynamic is one of the reasons shells evolved in the first place, more than 500 million years ago. Calcium, the basic building material, is a major component of seawater, and turning it into housing had obvious protective advantages. Largely for purposes of self-defense, shellfish quickly moved beyond mere shelter to develop a dazzling array of knobs, ribs, spines, teeth, corrugations and thickened edges, all of which serve to make breaking and entering more difficult for predators. This shell-building boom became so widespread, according to a 2003 paper in Science, that the exploitation of calcium carbonate by shellfish may have altered the earth's atmosphere, helping to create the relatively mild conditions in which humans eventually evolved.

Some shellfish also developed chemical defenses. Harasewych opened a museum locker and pulled out a drawerful of slit shells, gorgeous conical whorls of pink and white. "When they're attacked, they secrete large quantities of white mucus," he said. "We're doing work on the chemistry right now. Crabs appear to be repelled by it." Slit shells can repair predator damage, he said, indicating a five-inch-long scar where one shell had patched itself after being attacked by a crab. (Humans also attack, but not so often. A photograph on the cabinet door showed Harasewych in the kitchen with Yoshihiro Goto, the Japanese industrialist who donated much of the museum's slit shell collection. The two celebrated the gift, Harasewych noted, by preparing a slit shell dinner with special knives and sauces. Don't try this at home. "I've eaten well over 400 species of mollusk, and there are maybe a few dozen I'd eat again," said Harasewych. This one was "pretty foul.")

Some shellfish have even evolved to attract and exploit would-be predators. The United States happens to lead the world in biodiversity of freshwater mussels, a generally dull-looking, bad-tasting bunch—but with an astonishing knack for using fish as their incubators. One mussel species trolls a gluey lure in the water as much as a meter away from the mother shell. When a hungry fish snaps up this Trojan horse—it's actually a string of larvae—the larvae break loose and attach themselves to the fish's gills. For the next few weeks, part of the fish's energy goes to feeding these hitchhikers. In another mussel, the edge of the fleshy mantle looks and even twitches like a minnow. But when a fish tries to grab it, the mussel blasts the fish's gaping mouth with larvae. Yet another species, the snuffbox mussel from Pennsylvania's Allegheny River, actually has inward-curving teeth on the shell edge to hold a fish in a headlock while it covers its gills with larvae. Then it lets the bamboozled fish stagger off to brood baby snuffboxes.

A pretty shell, like a pretty face, clearly isn't everything.

Collectors these days tend to be interested in both beauty and behavior, which they sometimes discover firsthand. At the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia not long ago, collectors at a shell show swapped stories about the perils of fieldwork. A retired doctor had been bitten by a soft-shelled turtle while feeling for freshwater mussels. A diver had suffered an excruciating sting from a bristle worm. A retired pilot said he had had his middle finger ripped down both sides by a moray eel off the coast of Gabon, but added, "It's kind of worth it for a new species."

"New to science?" someone asked.

"The heck with science," he replied. "New to me."

Then the conversation turned to methods for separating mollusks from their shells. One low-tech approach is to leave the shells out for fire ants to clean, but high-tech works too. "Microwave cleaning is the greatest," one collector volunteered. Pressure builds up in the shell, he said, till it "blows the meat right out the aperture"—Phwap!—"like a cap gun."

So much for spiritual repose.

Downstairs at the museum, dealers had laid out a roomful of tables with thousands of microwaved, bleached, oiled and polished specimens. They included some of the most spectacular of the roughly 100,000 mollusk species now known, and they were liable to have come from almost anywhere on earth. A dealer named Richard Goldberg pointed out that animals with shells have been found living in the Marianas Trench, 36,000 feet deep, and in a Himalayan lake 15,000 feet above sea level. Though people tend to think of them as "sea shells," some species can survive even under a cactus in the desert. Goldberg added that he became interested in land snails after years as a seashell collector when a friend dared him to find shells in a New York City backyard. Goldberg turned over a few rocks and came up not just with three tiny land snails, but with three distinct species.

Another dealer, Donald Dan, bustled back and forth among his displays. Like a jeweler, he wore flip-up lenses on his gold-rimmed eyeglasses. At 71, Dan has silver hair brushed back in a wave above his forehead and is one of the last of the old-time shell dealers. Though more and more trading now takes place via the Internet, Dan does not even maintain a Web site, preferring to work through personal contacts with collectors and scientists around the world.

Dan said he first got interested in shells as a boy in the Philippines, largely because a friend's father played tennis. The friend, Baldomero Olivera, used to meet his father every day after school at a Manila tennis club. While he waited for his ride home, Olivera got in the habit of picking through the pile of shells dredged up from Manila Bay to be crushed and spread on the tennis courts. Thus Olivera became a collector and recruited his classmates, including Dan, to join him in a local shell club. Because cone snails were native to the Philippines and had an interesting reputation for killing people, Olivera went on to make their venom his specialty when he became a biochemist. He's now a professor at the University of Utah, where he pioneered the research behind a new class of cone-snail-derived drugs—including the one that relieved Phil Quinton's leg pain.

Dan became a collector, too, and then a dealer, after a career as a corporate strategist. Sometime around 1990, a rumor reached him through the collecting grapevine about a beautiful item of obscure identity being hoarded by Russian collectors. Dan, who now lives in Florida, made discreet inquiries, loaded up on trade items and, when visa restrictions began to relax, flew to Moscow. After protracted haggling, Dan obtained the prized shell, a glossy brown oval with a wide mouth and a row of fine teeth along one edge. "I was totally dumbfounded," he recalled. "You couldn't even imagine that this thing exists." It was from a snail that until then had been thought to have gone extinct 20 million years ago. Among shell collectors, Dan said, it was like finding the coelacanth, the so-called fossil fish.

Dan later purchased another specimen of the same species, originally found by a Soviet trawler in the Gulf of Aden in 1963. By looking inside through a break that had occurred when the shell rolled out of the net onto the deck of the ship, scientists were able to identify it as a member of a family of marine snails called Eocypraeidae. It's now known as Sphaerocypraea incomparabilis.

One of the few other known specimens belonged to a prominent Soviet oceanographer—"a very staunch Communist," Dan said—who at first refused to sell. Then the value of the ruble deteriorated in the 1990s. To earn hard currency, the Russians were providing submersibles for the exploration of the wreck of the Titanic. The staunch Communist oceanographer found himself in need of hard currency, too. So one of the operators on the Titanic job brought the shell with him on a trip to North America, and Dan made the purchase.

He sold that shell and his first specimen to a private collector, and in time that collection was given to the American Museum of Natural History in New York City, which hired Florida shell dealer Martin Gill to appraise its value. Dan's love affair with S. incomparabilis marked the high point of his life as a dealer: there are still only six known specimens in the world, and he had handled four of them.

A few years later, an American Museum of Natural History curator who was showing S. incomparabilis to a reporter discovered that one of the two shells was missing. The world of top shell collectors is relatively small, and an investigation soon suggested that, for Martin Gill, the temptation to pocket such a jewel-like prize had simply been too great. Gill had advertised a suspiciously familiar shell for sale and then sold it over the Internet to a Belgian dealer for $12,000. The Belgian in turn had sold it to an Indonesian collector for $20,000. An investigator for the museum consulted Dan. By comparing his photographs with one from the Indonesian collector, Dan spotted a telltale trait: the truncated 13th tooth in both specimens was identical. The shell came back to the museum, the Belgian dealer refunded the $20,000 and Gill went to prison.

It was proof that conchylomania lives.

Richard Conniff's new book, Swimming With Piranhas at Feeding Time, includes many stories he's written for the magazine.

Sean McCormick is a Washington, D.C.-based photographer.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/richard-conniff-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/richard-conniff-240.jpg)