Man-Eating Lions of Tsavo Did Indeed Eat People, Teeth Reveal

Dental clues confirm some rumors about the ravenous cats of Tsavo, while also raising new questions

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/d7/84/d7840dd3-d34b-47f2-94e6-b7bb7604976f/ayh25g.jpg)

They’re two of the most notorious killers in history: The lions of Tsavo, a pair of maneless males implicated in dozens of deaths before they were shot by Colonel J.H. Patterson in 1898. Their depredations were legendary enough to inspire a major motion picture, The Ghost and the Darkness, back when Val Kilmer was an A-list celebrity. Yet legends often overshadow reality, especially when we look into the maws of creatures that developed a predilection for human flesh. A new study by paleoecologist Larisa DeSantis and zoologist Bruce Patterson (no relation), published in Scientific Reports, helps disentangle myth from reality when it comes to Africa’s most famous man-eaters.

There’s something deeply unsettling about the concept of being eaten. While today’s lions and big cats kill people every year, beasts that take the next step and actually consume humans send a shiver down our spines. Those disturbing dining habits no doubt fed the celebrity of the Tsavo lions, said by Colonel Patterson to have been responsible for the deaths of 135 people. The actual total was probably far lower—a 2009 study of chemical traces in the lions’ teeth estimating that the two consumed about 35 people—but they still ate humans often enough that signs of their unusual menu choices should be visible on their teeth.

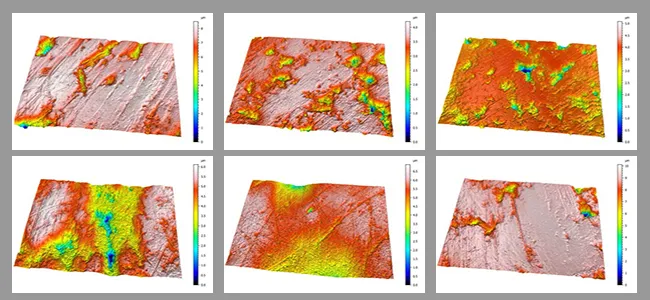

This is where DeSantis and Patterson comes in. For those who scour bones, teeth not only lend insight into what kind of food an animal evolved to eat—they also record what an individual animal was eating in the days and weeks before death. These microscopic clues are called microwear, and include scratches and pits that can be linked to particular types of foods. For the new study, DeSantis and Patterson looked at the microwear preserved on the teeth of the Tsavo lions—as well as the Mfuwe lion that ate six people in 1991—to see if their teeth showed a shift in diet compared to other lions, cheetahs and hyenas.

They were especially on the lookout for signs the lions were cracking the skeletons of their victims. They already had eyewitness testimony. In his account of what transpired at Tsavo, Colonel Patterson wrote: “I have very vivid recollection of one particular night when the brutes seized a man from the railway station and brought him close to my camp to devour. I could plainly hear them crunching the bones, and the sound of their dreadful purring filled the air and rang in my ears for days afterwards.” Now the researchers wanted evidence.

If the Colonel was right, such habits would have undoubtedly left their signature on the lions’ teeth, with microwear clues confirming the hunter’s colorful account.

Yet DeSantis and Patterson didn’t find corroboration for this chilling part of the story. “We were surprised to see no evidence of extreme durophagy”—which is paleo-speak for chewing hard food like bones—DeSantis says. That lack of evidence also ran counter to one of the traditional explanations of the lions’ man-eating behavior. It was thought that a local outbreak of a disease called rinderpest had wiped out the zebra and wildebeest that the lions normally preyed on, making the cats desperate enough to prey on humans, who the lions then consumed entirely. But the new study reveals that the lions were not scavenging buried humans or crunching bones out of desperation.

“We thought we were going to provide concrete evidence that these lions were scavenging and thoroughly consuming carcasses before they died,” DeSantis says. Instead, she notes, “the man-eating lions have microscopic wear patterns similar to captive lions that are typically provided with softer food.” In the case of the lions kept at the Smithosonian’s National Zoo, curator of great cats Craig Saffoe says the lions “get a base diet of ground beef, supplemented with specific vitamins and nutrients six days a week,” with a whole frozen rabbit once a week and defleshed beef bones twice a week.

But for the Tsavo and Mfuwe lions, a good proportion of that “softer food” was human flesh.

Exactly why the Tsavo and Mfuwe lions turned to hunting humans remains a mystery. Still, DeSantis and Patterson point out some potential contributing factors. The Mfuwe lion, as well as one of the Tsavo lions, had extreme injuries to their jaws. They wouldn’t have been as adept at taking their typical prey, so soft, tasty humans would have offered an attractive alternative. Even then, DeSantis says, humans were a food of last resort and the lions were primarily focused on the soft parts. These were not devilish skeleton crunchers, but injured cats doing what they could to survive.

The new study is a reminder that well-kept historic specimens can often reveal ancient secrets later down the road, DeSantis notes. But the upshot is more than ancient history. “We need to stop thinking of humans as on the top of the food chain,” DeSantis says. The fossil record is clear that humans have been prey for other animals for our entire history, and, DeSantis points out, 563 people were killed by lions in Tanzania alone between January of 1990 and September of 2004. Getting in your car to drive to work is still far more likely to be fatal than meeting a lion, of course. But that statistic is a reminder that other species do not recognize our self-important strut as somehow outside or above nature. For some beasts, we are still prey.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RileyBlack.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RileyBlack.png)