Unraveling the Genetic History of a First Nations People

By looking at the DNA of Tsimshian people before and after European contact, researchers paint a more nuanced history

:focal(319x195:320x196)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/bb/4e/bb4eb06e-9e05-48ad-b0ee-dbb2cdcddac2/tsimshian1.jpg)

Humans tend to view ourselves in terms of our impact on the world around us: the wars we’ve waged, the land we’ve settled, the machines we’ve made. But the natural world exerts a reciprocal force on us, shaping the members of our species down to our very cells. The macroscopic challenges we face as societies are reflected in our microscopic DNA, transmitted and transmuted across time as we—like all other animals—slowly but steadily evolve.

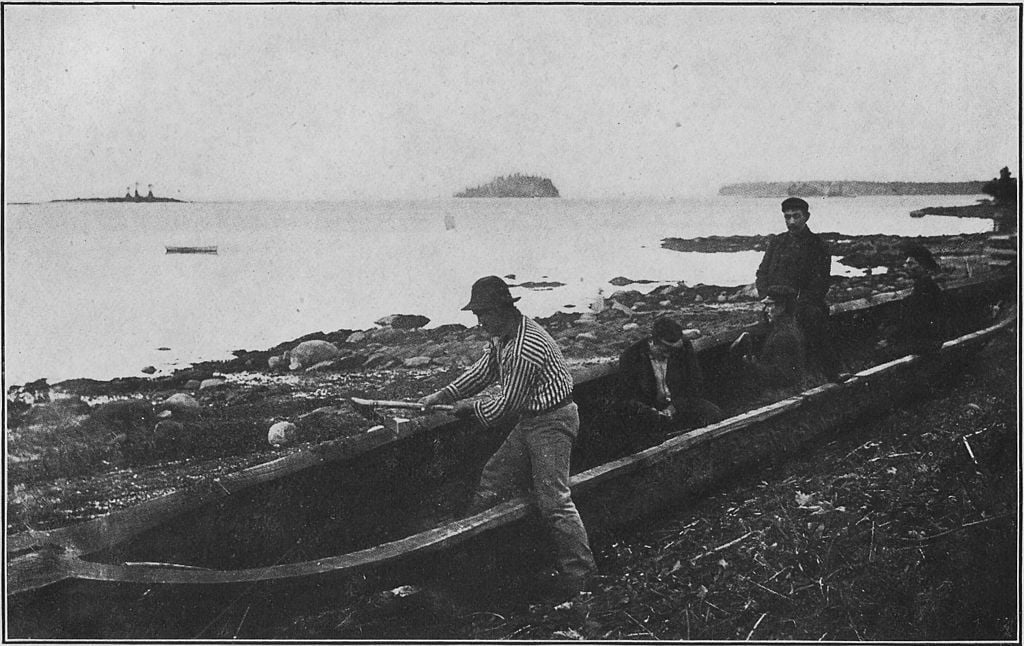

From an evolutionary standpoint, it was not long ago that the Tsimshian people of modern-day Alaska and British Columbia were first confronted with European settlers—roughly 175 years, a mere handful of generations out of the Tsimshian’s 6,000-year American history. But that fateful encounter, which introduced smallpox and other alien ailments into their population, decimated the Tsimshian and threatened to compromise their genetic diversity in the years ahead.

This landmark moment in Native American history captured the imagination of John Lindo, a genetic anthropologist at Emory University who delved deep into Tsimshian DNA as lead author on a just-published paper in the American Journal of Human Genetics. Lindo focused his research on the Tsimshian in an effort to understand the genetic dynamics surrounding their population collapse, which could shed light on the experience of many other Native American groups upon first contact with Europeans.

Employing cutting-edge genomic analysis, Lindo and his team compared modern Tsimshian DNA (obtained with consent from Tsimshian residents of Prince Rupert Harbour, Canada) against DNA found in millennia-old ancestral specimens (exhumed under community supervision and housed in the Canadian Museum of History), correcting for the degradation of the ancient DNA over time.

What the researchers learned about the Tsimshian—on both sides of the fateful 19th-century population collapse—adds considerable nuance to the genetic and social history of a prominent First Nations people.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/de/f3/def3fff2-ee29-4fdb-bbdd-5c297060fcde/tsimshian2.jpg)

What most surprised researchers was that the population of the ancient Tsimshian people was in decline long before the arrival of Europeans. Slowly and steadily, since their first settlement in modern Canada, the Tsimshian had been decreasing in number, not expanding as one might presume.

“We were completely expecting to see the population expand after that founding effect, when they entered from the Bering Strait,” Lindo says. “It was a big surprise to see that the population was on a steady decline before European contact.”

For Lindo, this finding drives home a valuable lesson: all Native American peoples have their own stories to tell, and academics do a disservice when they proffer sweeping assertions. “Native Americans all have unique evolutionary histories,” he says. “They can’t just be summed up as ‘one race’ of Native Americans all experiencing the same thing after entering the Americas.” Many Native American populations swelled following their establishment, but the Tsimshian evidently took a different course.

The eventual arrival of disease-bearing Europeans in the region ratcheted up the Tsimshian decline to astonishing proportions: in the 19th century alone, Tsimshian numbers fell by 57 percent. A major focus of Lindo’s paper was the period in the wake of this collapse. How did the genomes of the Tsimshian respond to this traumatic evolutionary event?

What Lindo found was that, in terms of the variety in their genomes, the Tsimshian rebounded surprisingly well. “We didn’t see a decrease in genetic diversity,” he says, “which would have been bad for fighting off diseases and things like that.” Rather, the Tsimshian population maintained the crucial genetic diversity that any population needs to survive.

“It seems to be because, after European contact, this particular people started intermarrying with others,” Lindo says, “which likely wasn’t the case beforehand. And intermarrying with immigrants as well.” This was an important factor in keeping their population genetically resilient. “It increased genetic diversity,” he says, “which mitigated to a certain extent the negative effects of the collapse.”

From the first stages of his research, Lindo was in direct contact with cultural ambassadors of the Tsimshian community, who advised his team on how to respectfully present its findings and received co-authorship credit for their input. “They reviewed the paper before we submitted it,” Lindo says, “to make sure the wording was sensitive to their culture and their whole histories.”

One key takeaway from the Tsimshian reviewers’ feedback was that speculative “storytelling” was to be avoided in the paper. Where Lindo and his team don’t know something—such as precisely why the population experienced a long slow decline—they admit it rather than invent a narrative.

Lindo is hopeful that the Tsimshian people more broadly will find value in the new research. “After European colonization, there was a big disruption in their culture, and in transmitting their oral histories from one generation to the next," he said. "And this might help them connect to their ancient history before European contact a little better.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/DSC_02399_copy.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/DSC_02399_copy.jpg)