Mapping the Smells of New York, Amsterdam and Paris, Block by Block

Designer and cartographer Kate McLean charts the sweet scents and pungent odors that fill a city’s olfactory landscape

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/24/35/2435d5ed-10a2-41e4-a4e5-5a4d79df3a9b/smelliest_block_nyc__kate_mclean.jpg)

In 2011, Kate McLean, a designer and cartographer, was pretty new to the Scottish city of Edinburgh. As a graduate student studying fine art, she sought to use design to probe people’s emotional connections to a place, and had the novel idea of charting the surfaces and textures people encountered throughout the city—in essence, creating a tactile map of her adopted home.

Soon afterward, she was tasked with an unexpected assignment. “I was told that I needed to do a solo exhibition, and I had eight days to get it all made and set it up,” she says. “I wanted to do something new, so I said I was going to make a smell map. And everyone just looked at me, like, ‘what?’”

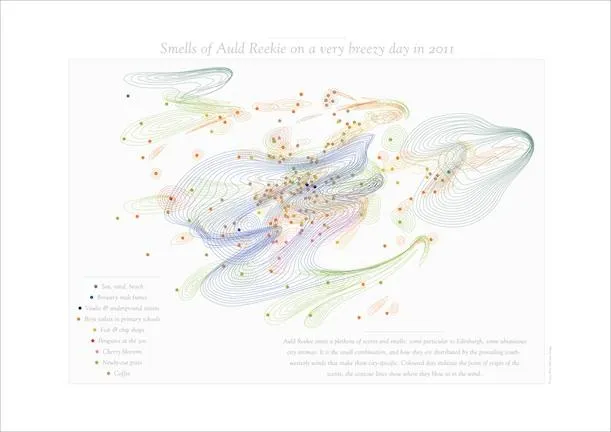

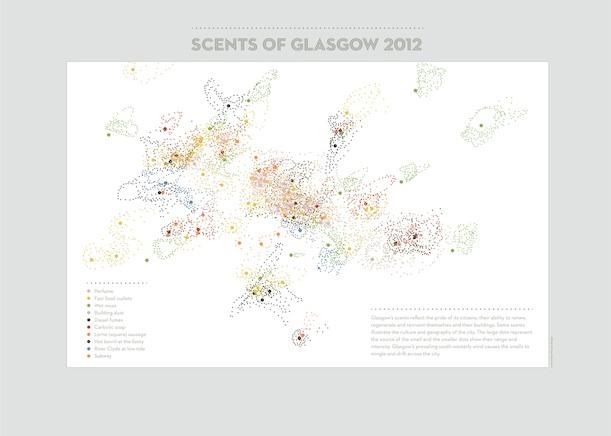

McLean’s smell map of Edinburgh, historically nicknamed “Auld Reekie” due to its pungent aromas, included everything from the malt fumes emanating from breweries, to fish and chip shops, to the scent of “boys toilets in primary schools,” as she quaintly lists in her map’s legend. In the years since, McLean, now a lecturer at Canterbury Christ Church University, has created smell maps for a total of 6 different cities, charting the scents of fast food, wet moss, sunscreen and diesel fuel.

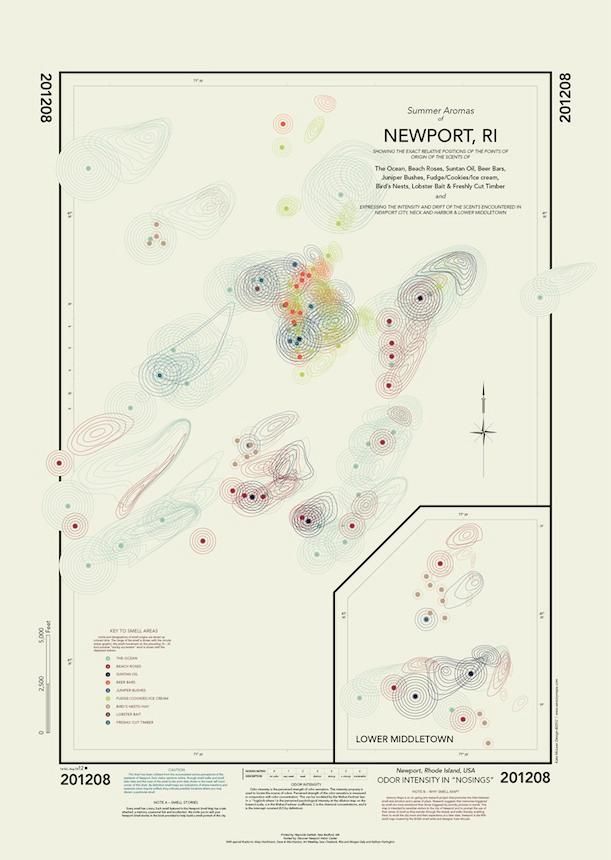

In 2011, she even created a special ultra-detailed map of an area on Manhattan’s Lower East Side (at top) after it was named “The Smelliest Block in New York” by New York Magazine (cheap perfume, stagnant water and dried fish apparently played an important role in earning the area the distinction).

Over time, the initial skepticism she encountered has been largely replaced by fascination. “People have told me that they’ll never be able to go outside and experience their city in quite the same way,” she says. “It’s not that they’ll be looking for those smells, but they’ll just be aware of the fact that they’re smelling all the time.”

Her method is admittedly more in the realm of art than science. “It’s not a large data set. It’s not about asking 50,000 people to define the ’Paris smell,’” she says. “What I’m really interested in are the stories and emotional connections that people use when describing smells.”

In pursuit of this goal, when creating a map for each city, she individually interviews a range of people—longtime residents, new arrivals and tourists—and sometimes even walks with them across their neighborhoods as they describe the smells they encounter. For her most recent smell map, of Amsterdam, she walked with “trained noses” provided by a fragrance company to gain another perspective on the scents of the city. She tracks the source of the smell down, and depending on the map, draws contours or plots points that describe the range and intensity of smells as they waft from their sources.

Oftentimes, a deeper examination is required to fully understand the smells people report. “Someone once told me, ‘Paris smells like honey,’” she says. “Eventually, I figured it out. It’s the number of parquet floors, and honey smell of the wax polish that they use on them.”

Asking people about the smells they associate with their home city has frequently yielded the sorts of emotional connections McLean started out looking for. “Smell is remarkably evocative of place,” she says. “When I was mapping Newport last summer, a lot of people said ‘The smell of the ocean is the smell of home. As soon as I cross the bridge, I know where I am.’”

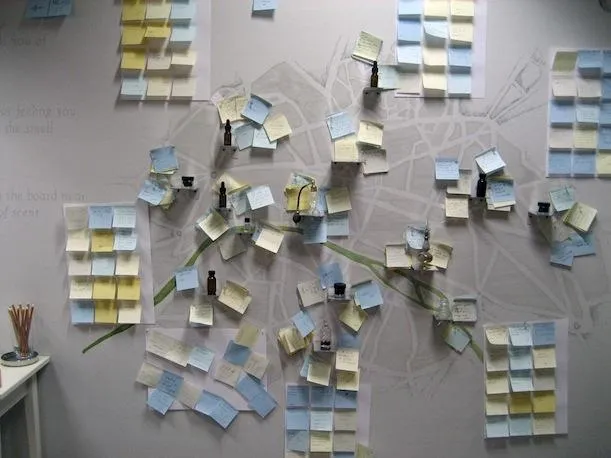

For installations, she’s experimented with actually including the smells described on the maps for visitors to experience—on her Paris smell map (above), she attached bottles of perfume and other substances for viewers to spray. She’s even thinking of adding a scratch-n-sniff component to her maps in the future to simulate the olfactory sensation of walking through the cities.

For McLean, watching visitors enjoy both looking at and smelling her installations has become its own pleasure. “There’s something very meditative about smelling. It’s a long, slow process, very thoughtful and reflective,” she says. “And it’s beautiful to witness people enjoying the experience of smelling and consciously thinking about it.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/joseph-stromberg-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/joseph-stromberg-240.jpg)