Mating Snakes Engage in a Literal Battle of the Sexes

Male and female red-sided garter snakes have antagonistic genitals, evolved to further the interests of their respective gender

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20131112065142garter-small.jpg)

When it comes to sex, males and females are not always equal in their desires. No, you haven’t stepped into a couples therapy class.

Welcome to the animal kingdom, where what’s good for one gender could in fact be detrimental for the other. Similar to the struggle between a parasite and its host, some species are locked in an evolutionary arms race between the sexes, with each gender battling to put its best interests forth. Although male and female sexual preferences and tactics are as variable as the thousands of species they represent, a particular species of snake provides an interesting example of conflict that can occur during mating itself, researchers describe in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B.

The authors focused their paper on an intimate discussion of red-sided garter snake behaviors. When red-sided garter snakes are ready to mate, several dozen males find their way to a female. Just as she is emerging from hibernation into the warm spring air, the males–which slithered forth days earlier–swarm over her, forming a “mating ball.” Here’s one, from thamnophis14 on YouTube–it’s mesmerizing to watch:

Rather than pick the nicest looking or most impressive male, mating is more of a crapshoot for the female, with the closest male latching on as soon as the female presents herself by opening her cloaca, an orifice that leads into the vagina. But sometimes, things get a bit ugly: males may go so far as to cut the female’s oxygen supply off, which triggers a panic reaction in the female, who releases feces and musk. In doing so, however, she opens up her cloaca, effectively allowing the males to sneak in and get what they want.

Female red-sided garter snakes, not surprisingly, prefer to get copulation over and done with. They attempt to bid their mate goodbye as soon as he has handed over his sperm, and sometimes, even sooner than that. This way, females can get on with their business–which oftentimes entails finding another mate of their choosing. To shake the males off, the female may perform a “body roll,” essentially flipping around until the male detaches.

The males, however, prefer to stick around. The longer they hold on, the more sperm they can transfer and the less chance that another male will snag their female. Sometimes, males take their mate guarding to extremes. Red-sided garter snake males, like some other snake species, may physically plug up the female’s genitals with a ”gelatinous copulatory plug,” preventing her from mating with other males even if he is not around, and stopping her from potentially ejecting his sperm after mating. Over the next few days, however, the plug will dissolve, giving the female a second chance at selecting a mate of her choice under less frantic circumstances.

Researchers aren’t sure what triggers the males to plug up the females. They suspect the female’s “body roll” behavior–essentially a “Get off me!” signal–may have something to do with it. Powerful muscular movements within the female’s vagina may also help to push the male out, but at the same time increase the chances that he attempts to issue a plug.

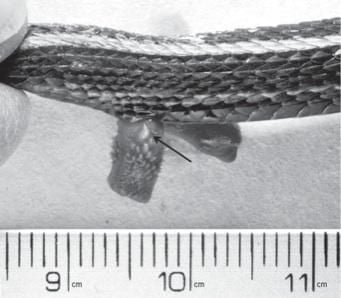

Finally, to further aid in mating, males of red-sided garter snakes and some other species evolved a special organ whose name and appearance resembles something from a medieval torture chamber: the basal spine. A blunt apparatus covered in small spikes, the basal spine acts as a “grappling hook” for allowing the male to hold the female in place during mating (a process that often makes the females bleed, by the way), some researchers suspect. Overall, however, the basal spine’s adaptive role is a bit of a mystery.

To find out how the snakes’ genital traits influence sexual conflict and behaviors, the researchers caught 42 wild red-sided garter males in Manitoba, Canada, during the spring mating season. They also scooped up newly emerged females, and put two of those females into a small outdoor enclosure with the males. They allowed the snakes to mate naturally while they monitored the duration of copulation, the behaviors involved and whether or not the males left a mating plug behind. Males that copulated for five minutes or more were more likely to leave a plug behind, they found, and the longer the copulation period, the larger the plug.

Afterwards, they divided the males into two groups. Unlucky males in the experimental group suffered a bit of genital mutilation: the researchers clipping off the animals’ basal spines (they did use anesthesia). Males in the other group were left intact. After a four day recovery period, the males were again introduced to two new, unmated females.

This time, the researchers found, the males without a basal spine mated for a significantly shorter duration than the control group. Eight out of 14 of the males lacking basal spines copulated for less than one minute (they were usually shaken off by female body rolls) and did not leave a plug in the female. Moreover, five of them did not manage to eject any sperm.

Next, it was the females’ turn. The researchers collected 24 unmated females. They anesthetized the lady parts of half the females, and used a placebo injection for the others. Females that lost feeling down south, they found, mated for significantly longer than females that were not anesthetized. However, the anesthetized females, compared to the natural ones, received smaller mating plugs even though the copulation period was longer. This may be because those numb females did not struggle, the researchers write, or it could be that the plugs adhere better to engaged vaginal muscles.

Although more experimentation is needed to work out some of the specifics, genital features clearly play significant roles in sexual conflict in this species, the researchers write. In other words, males and females are out for themselves. The males’ strategy increases the chance that they will inseminate a female and thus pass on their own genes, while the females’ strategy increases the chance of insemination from a male they actually want. “The evolution of the basal spine allows males to gain more control over copulation duration, forcing females to evolve some counter trait to regain some control, leading to sexually antagonistic coevolution,” the authors write.

While these tactics may sound brutal to a human reader, the fact that the snakes have evolved these traits prove that they work for the species. And as a small comfort for the snakes, this battle of the sexes is nowhere near the level of brutality seen in the mating behavior of bed bugs–perhaps one of the most graphic example of sexual conflict in the animal kingdom. For that species, males impale the female’s abdomens in a process called traumatic insemination. Compared to being stabbed in the gut, mating plugs may not seem so extreme after all.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Rachel-Nuwer-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Rachel-Nuwer-240.jpg)