A Universal Flu Vaccine May Be On the Horizon

Choosing the viral targets for the seasonal flu vaccine is a gamble. Sometimes, like this year, the flu wins

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/59/3e/593ec851-2955-4880-b0ae-49a29d2947a0/42-64774754.jpg)

Every year it's a frustrating, high-stakes guessing game: Which strains of the flu virus are likely to circulate the following year? Because of the way vaccine production works, medical experts must decide which strains to target long before flu season sets in, and once the choice is made, there's no altering course. Sometimes, as with the 2014-15 vaccine, the experts guess wrong.

Getting this season's flu shot reduced the risk of having to visit the doctor for a flu-related illness by just 23 percent, according to a January 16 Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). When the vaccine is a good match for the year's most common strains, effectiveness reaches 50 to 60 percent.

Vaccinations against the flu are about more than avoiding a week of the sniffles. The seasonal flu can create serious health issues, especially among people under age 2 or over age 65 and those with weakened immune systems or other medical conditions. The World Health Organization estimates that 3 to 5 million people globally become severely ill with the flu each year, with 250,000 to 500,000 annual deaths.

Though this season's vaccine match is a poor one, experts stress that getting a shot is still the right thing to do. For one thing, the strains that this vaccine is designed to prevent may begin wide circulation later in the flu season. The vaccine can also prevent some infections of mismatched strains and reduce the severity of others, allowing people to avoid hospitalization or even worse outcomes.

And now there's hope on the horizon that might end the annual attempts at flu prognostication. Scientists could be closing in on a “universal vaccine” that can effectively fight multiple strains of influenza with a lifetime dose, like the one that protects people against measles, mumps and rubella. A one-and-done flu vaccination would likely be a boon to public health, because it would encourage more people to get the shot. With annual doses, CDC surveys show that vaccination rates in the U.S. have hovered around just 40 percent at the beginning of the past two flu seasons, in part because many people find annual shots too inconvenient.

“Establishing 'herd immunity' by having as many of the general population as possible receiving the vaccine is extraordinarily important, as evidenced by the recent measles outbreaks,” says Matthew Miller at McMaster University in Ontario. Thanks to widespread inoculations in the 20th century, measles is now rare in the U.S. However, dozens of new cases have been reported in California and nearby states since mid-December, creating an outbreak that has been linked to infected visitors at Disneyland. According to the California Department of Public Health, about 20 of the confirmed patients were unvaccinated.

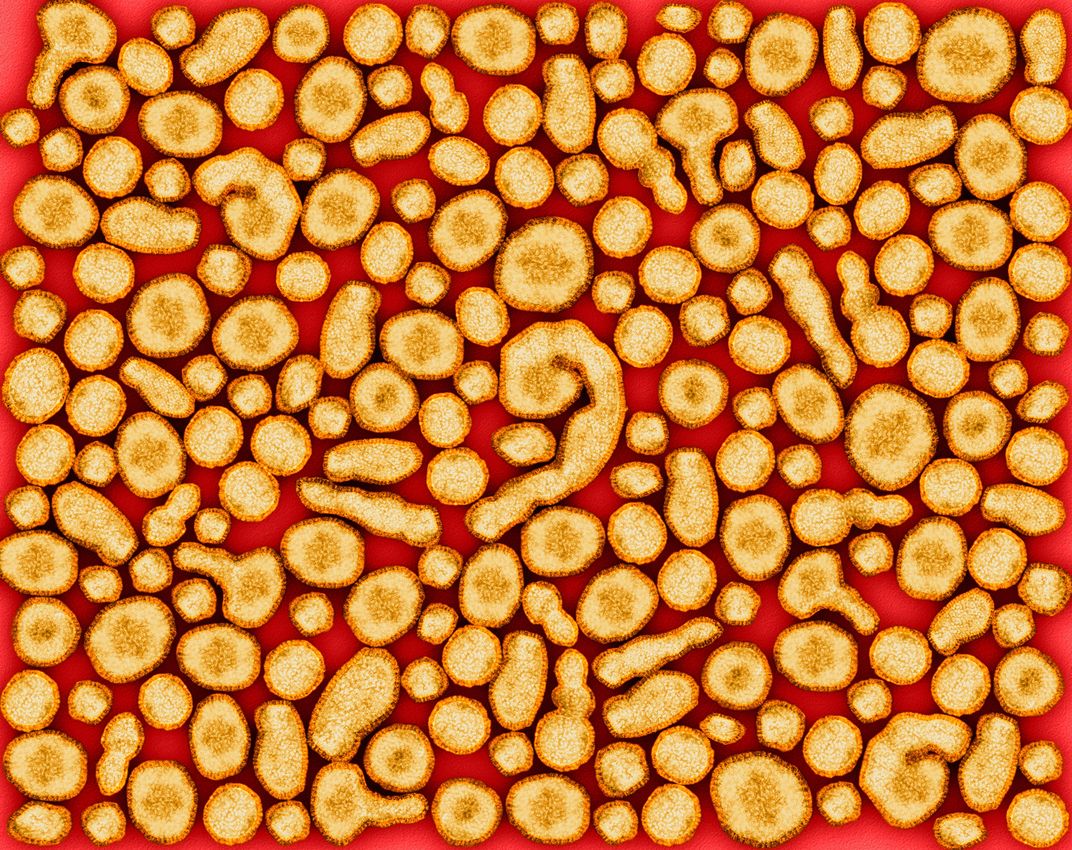

The tricky part of developing a flu vaccine is that the virus is constantly and rapidly changing. Genetic mutations alter the structure of the virus' surface proteins, which changes properties such as how vulnerable it is to vaccines, how easily it moves from person to person and how well it can resist antiviral drugs. Since October 1, 2014, the CDC has characterized 462 different influenza viruses.

The most commonly made flu vaccines expose the body to a “sample” virus that's either inactivated or weakened, so that it can begin to create antibodies during the two-week period after vaccination. Those antibodies protect against the same viral strains used to make the vaccine. Influenza A and B are the primary viruses that infect people each season, so two influenza A strains (an H1N1 virus and an H3N2 virus) and one or two influenza B strains are included in the seasonal drug.

But it's a time-consuming process to produce and deliver the millions of doses that are needed by the start of the season in early December. That means a team of experts has to make their best guess on which viruses to include months before flu season arrives. This year an estimated 70 percent of the most common H3N2 viruses floating around have altered from those used in vaccine production, which means the vaccine is trying to combat flu strains that didn't even exist when it was made.

U.S. experts will soon have to try and outwit the flu again, when a group begins meeting at the Food and Drug Administration in early March to start designing the 2015-16 vaccine. Once manufacturing begins, they can only watch and hope that the strains they choose will be the ones most commonly circulating during next year's flu season.

But this system could soon be ripe for change. Researchers announced earlier this month that they are about to begin clinical trials on a universal vaccine that could prevent against all strains of the influenza A virus with a one-time shot. “The vaccine could become a reality in as few as five to seven years, if clinical trials go smoothly,” says Miller, one of the vaccine's creators.

Described in the February 2015 edition of the Journal of Virology, the vaccine hinges on a class of antibodies capable of combating the wide range of influenza A viruses. They target the region of a viral protein known as the hemagglutinin stalk domain, which is like the stick on a viral protein "lollipop"—the flavors of the candy top may change when viruses mutate, but the stick stays the same and so will continue to be vulnerable to a universal antibody.

Miller and his colleagues from McMaster University and the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai have so far tested the vaccine in mice and ferrets. When the animals were infected with the viral strain that was well matched to the conventional vaccine, both vaccines performed comparably.

“However, when animals were infected with a 'mismatched' virus, those given the conventional vaccine died, while those given the universal vaccine survived. This is the huge breakthrough,” Miller says. Strategies to incorporate a universal influenza B component into the vaccine are in development but are less advanced so far, Miller notes. Influenza B is of slightly less concern, he adds, because only type A flu viruses are known to have caused pandemics and notable outbreaks, like the H5N1 bird flu scare. Still, he calls the flu B component “a high priority.”