Men Commit Scientific Fraud Much More Frequently Than Women

According to a new study, they’re also much more likely to lie about their findings as they climb the academic ladder

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Surprising-Science-scientist-fraud-631.jpg)

Next time you’re reading about a scientific finding and feeling a bit skeptical, you may want to take a look at the study’s authors. One simple trick could give you a hint on whether the work is fraudulent or not: check whether those authors are male or female.

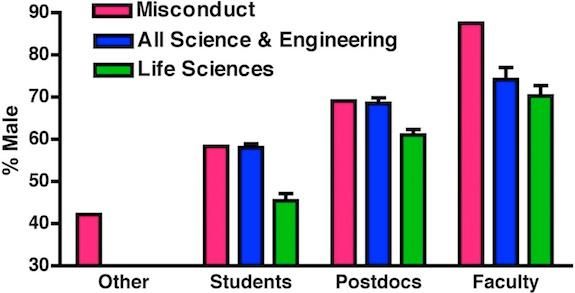

According to a study published yesterday in mBio, men are significantly more likely to commit scientific misconduct—whether fabrication, falsification or plagiarism—than women. Using data from the U.S. Office of Research Integrity, this study’s authors (a group that includes two men and one women but we’re still trusting, for now) found that out of 215 life science researchers who’ve been caught misbehaving since 1994, 65 percent were male, a fraction that outweighs their overall presence in the field.

“A variety of biological, social and cultural explanations have been proposed for these differences,” said lead author Ferric Fang of the University of Washington. “But we can’t really say which of these apply to the specific problem of research misconduct.”

Fang first became interested in the topic of misconduct in 2010, when he discovered that a single researcher had published six fraudulent studies in Infection and Immunity, the journal of which he is editor-in-chief. Afterward, he teamed up with Arturo Casadevall of the Albert Einstein College of Medicine to begin systematically studying the issue of fraud. They’ve since found that the majority of retracted papers are due to fraud and have argued that the intensely competitive nature of academic researcher engenders abuses.

For this study, they worked with Joan Bennett of Rutgers to break down fraud in terms of gender, as well as the time in a scientist’s career when fraud is most likely. They found that men are not only more likely to lie about their findings but are disproportionately more likely to lie (as compared to women) as they ascend from student to post-doctoral researcher to senior faculty.

Of the 215 scientists found guilty, 32 percent were in faculty positions, compared to just 16 percent who were students and 25 perecent who were post-doctoral fellows. It’s often assumed that young trainees are most likely to lie, given the difficulty of climbing the academic pyramid, but this idea doesn’t jive with the actual data.

“Those numbers are very lopsided when you look at faculty. You can imagine people would take these risks when people are going up the ladder,” said Casadevall, “but once they’ve made it to the rank of ‘faculty,’ presumably the incentive to get ahead would be outweighed by the risk of losing status and employment.”

Apparently, though, rising to the status of faculty only increases the pressure to produce useful research and the temptation to engage in fraud. Another (unwelcome) possibility is that those who commit fraud are more likely to reach senior faculty positions in the first place, and many of them just get exposed later on in their careers.

Whichever the explanation, it’s clear that men do commit fraud more often than women—a finding that shouldn’t really be so surprising, since men are more likely to indulge in all sorts of wrongdoing. This trend also makes the fact that women face a systemic bias in breaking into science all the more frustrating.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/joseph-stromberg-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/joseph-stromberg-240.jpg)