Apollo 11 Astronaut Michael Collins on the Past and Future of Space Exploration

On the occasion of the lunar landing’s 50th anniversary, we spoke to the former director of the National Air and Space Museum

:focal(1126x1410:1127x1411)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/50/16/5016b9d7-7a93-494d-aa28-5468c7053063/apollo_11_lunar_module.jpg)

On July 28, 1969, four days after Apollo 11 splashed down in the Pacific Ocean, famed aviator Charles Lindbergh, who made the first solo, non-stop flight across the Atlantic in 1927, wrote a letter to Michael Collins, one of the three astronauts on the first mission to land on the moon. “I watched every minute of the walk-out, and certainly it was of indescribable interest,” he wrote. “But it seems to me you had an experience of in some ways greater profundity—the hours you spent orbiting the moon alone, and with more time for contemplation. What a fantastic experience it must have been—alone looking down on another celestial body, like a god of space!”

As crewmates Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin walked on the lunar surface, Collins orbited 60 nautical miles above. His legacy in the history of space exploration, however, extends beyond his role on Apollo 11. He became director of the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum in 1971, overseeing the opening of the main building on the National Mall in 1976, a key institution in educating the public about spaceflight and aviation. In 1974, he published what is widely regarded as the greatest astronaut autobiography ever written, Carrying the Fire: An Astronaut’s Journeys.

During the lunar landing, Collins was one of the people not watching the event on television. After the lunar module Eagle with Armstrong and Aldrin aboard separated from the command module Columbia, Collins began nearly 28 hours of orbiting the moon alone. He monitored the mission via chatter between Mission Control and the Eagle, but whenever he circled around the far side of the moon, he was cut off from all communications. After the Eagle landed, Collins proceeded to conduct housekeeping chores aboard Columbia, including attempting (unsuccessfully) to locate the Eagle with his sextant, dumping excess water produced by the fuel cells, managing a problem with the coolant in the spacecraft, correcting the trajectory of the command module and preparing for Armstrong and Aldrin to return.

A little more than six-and-a-half-hours after touchdown, Armstrong climbed down the ladder outside the lunar module to take the first steps on another world. “So here it is,” Collins says today, remembering the moment. “What is Neil gonna say? ‘One small…’ now wait a minute, I’m three degrees off on that inertial platform, so never mind what Neil’s saying down there.”

**********

We memorialize that first step on the moon, the parallel rectangular tread of the boot print engraved on our minds and our coins, but the story of Apollo is larger than any one step. Flying to the moon for the first time, roughly 240,000 miles from Earth (the previous record was 850 miles on Gemini 11), could almost be viewed as the greater accomplishment—in fact, if one man had done it alone, it might be viewed that way. “[W]atching Apollo 8 carrying men away from the earth for the first time in history [was] an event in many ways more awe-inspiring than landing on the moon,” Collins writes in Carrying the Fire.

Among other awe-inspiring deeds: Eugene Cernan and Harrison "Jack" Schmitt walked on the moon’s surface for 75 hours during Apollo 17; Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin walked for about two and a half. Some of the astronauts (the moonwalkers on Apollo 15, 16 and 17) drove cars on the moon.

Humankind’s first journeys beyond the haven of Earth, into the void and the desolate places beyond, is a story filled with multifold perspectives and endless contemplations. If Apollo didn’t modify the human condition, it’s hard to think of an event that did.

From his perch in the command module, Collins, due to a knack for storytelling or his unique perspective, and likely both, was able to grasp the magnitude of voyaging to the moon and share it with others perhaps better than anyone, if not at the time then in retrospect.

“It is perhaps a pity that my eyes have seen more than my brain has been able to assimilate or evaluate, but like the Druids at Stonehenge, I have attempted to bring order out of what I have observed, even if I have not understood it fully,” Collins writes in Carrying the Fire. “Unfortunately, my feelings cannot be conveyed by the clever arrangement of stone pillars. I am condemned to the use of words.

Carrying the Fire

The years that have passed since Neil Armstrong, Buzz Aldrin, and Michael Collins piloted the Apollo 11 spacecraft to the moon in July 1969 have done nothing to alter the fundamental wonder of the event: man reaching the moon remains one of the great events―technical and spiritual―of our lifetime.

**********

The Apollo program was perhaps ahead of its time. President Kennedy announced to Congress in 1961 that “this nation should commit itself to achieving the goal, before this decade is out, of landing a man on the moon and returning him safely to the Earth,” only 20 days after Alan Shepard became the first American to fly in space—a flight that lasted a little over 15 minutes and hit a maximum altitude of 116.5 miles.

The decision to go to the moon was made before a rocket was designed that could take people there (although engineers at NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center were already toying with the idea), before doctors knew if the human body could endure microgravity for the required eight days (some medics thought the body wouldn’t be able to digest food properly, or that the heart and lungs would not function correctly), and before planetary scientists even knew if landing on the moon was possible (some hypothesized that the moon was covered in a deep layer of fine grains, and that a crewed spacecraft would sink into this material upon landing).

The Apollo program was driven forward by a combination of geopolitical will, singular vision, technological breakthroughs and sheer vision. As many have pointed out, humans have yet to return to the moon due to some combination of high costs and a lack of concrete benefits.

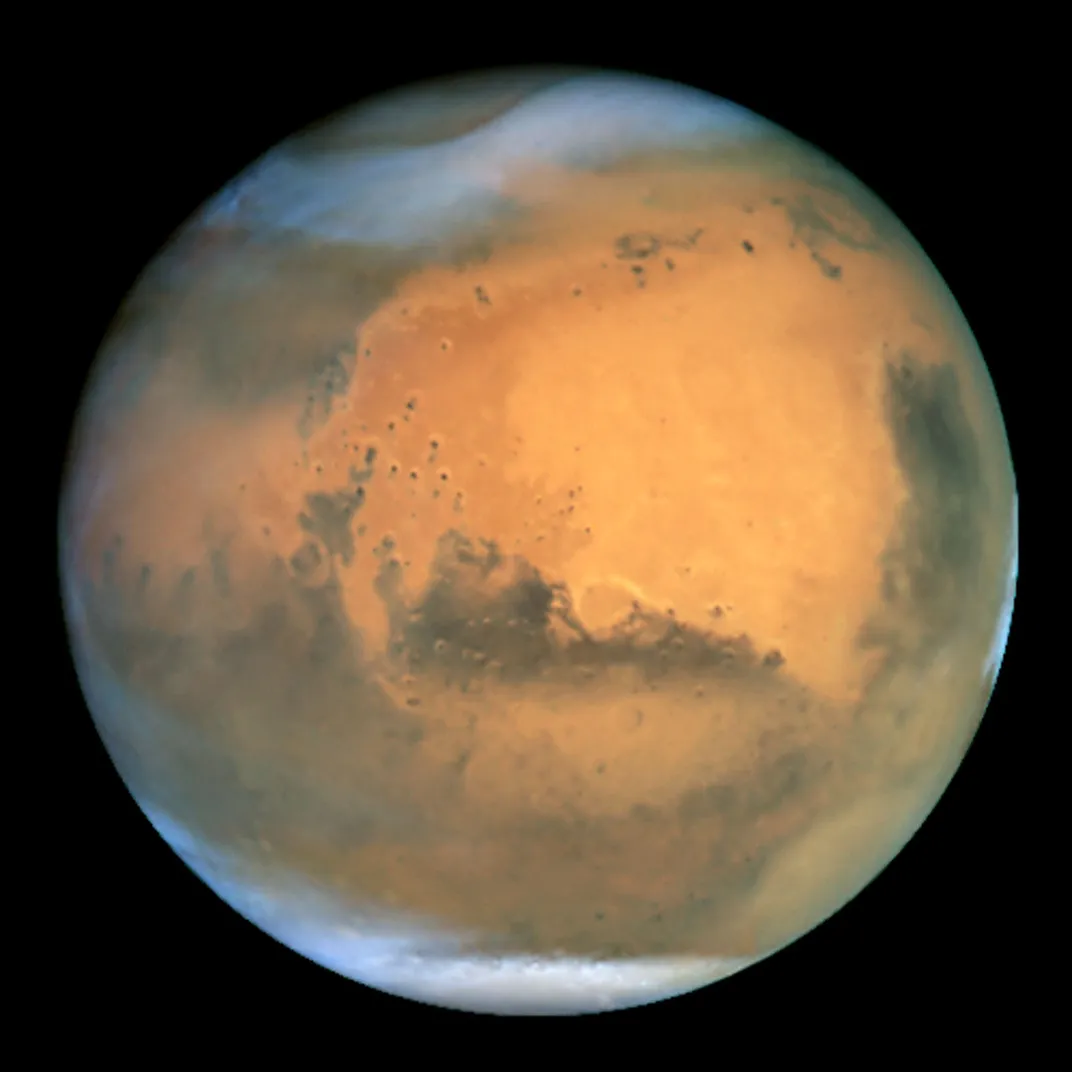

Today, like many of those involved in Apollo, Collins thinks humans should go to Mars. Similar to 1962, we don’t know exactly how to do that. We don’t know if humans can endure the radiation and microgravity of deep space for two or three years on a flight to Mars and back. We don’t know if they could endure the isolation. And most concretely, we don’t yet have the hardware to land a crewed spacecraft on Mars.

Collins describes the Apollo missions as a “daisy chain” of events that could have gone wrong—a failed docking, a botched landing, the refusal of the lunar ascent engine to fire and bring the astronauts back up from the surface—any one of which would have spelled disaster. He views a mission to Mars the same way, but believes that by unraveling the chain and considering all its components, the challenges are surmountable.

“You can pull that daisy chain apart and examine one little bud after the other, but I don’t think it’s those little itsy-bitsy buds that are the problem in that daisy chain, I think it’s just the totality of it all,” he says. “What do we think we understand, but it turns out we really do not understand? Those are the things that make a Mars voyage very very perilous.”

And the question always remains: Why should we go? Why now?

“I’m not able to put anything tangible on our ability to go to far-off places. I think you have to reach out for the intangibles,” Collins says. “I just think humankind has an innate desire to be outward bound, to continue traveling.”

The technologies required to fly to other worlds continue to improve, potentially making a future mission to Mars safer and more cost-efficient. The benefits are harder to measure, steeped in abstraction and subjectiveness. By no means do we live in a perfect world, but by refusing to venture outward, do we secure progress at home? Does one type of advancement stunt another, or do they move in parallel?

“We cannot launch our planetary probes from a springboard of poverty, discrimination, or unrest; but neither can we wait until each and every terrestrial problem has been solved,” Collins told a joint session of Congress on September 16, 1969. “Man has always gone where he has been able to go. It’s that simple. He will continue pushing back his frontier, no matter how far it may carry him from his homeland.”

Half a century ago, humanity left its homeland for the first time. Beyond astronomical and geological knowledge, the effort brought home a new perspective, one shared with the world through images and stories. It was a choice to go to the moon, and some would say we have a greater understanding of ourselves as a result.

“I think a lot of people don’t want to live with a lid over their head,” Collins says. “They want to remove that lid. They want to look up into the sky. They want to see things that they do not understand. They want to come to know them better, perhaps even physically go there and examine them, to see, to smell, to touch, to feel—that’s, to me, the impetus for going to Mars.”

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/bennett.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/bennett.jpg)