Striking Photos of the Past and Present of Papua New Guinea

From tribal traditions to urban strife in the island nation

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/99/de/99de2118-674a-449b-ac9c-d8cf15dbcf32/mar2018_d08_pngphoto-wr.jpg)

Is any place on the planet less familiar to Americans than heavily forested, mountainous, linguistically complex, faraway Papua New Guinea? The images on these pages document just a few points on the wide spectrum of life in PNG today. At one end is what might be called extravagant tradition. To see that, the photographer Sandro, who’s based in Chicago, went to the Eastern Highlands and attended the Goroka Show.

That’s a three-day festival where people from all over the country showcase their customs. In a makeshift studio Sandro photographed men and women wearing costumes unique to their villages.

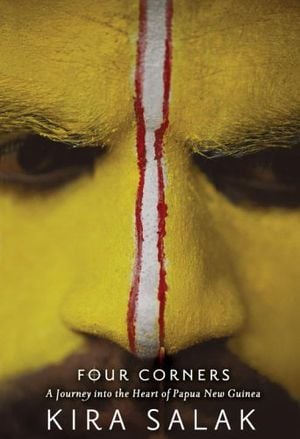

Four Corners: A Journey into the Heart of Papua New Guinea

At the age of twenty-four, Kira Salak took a three-month solo trip across Papua New Guinea, making her the first woman to have traversed the whole country.

This kind of undertaking is not without risk. Anthropologists rightly caution against ethnic stereotyping, and a Papuan elder in feathered regalia doesn’t stand in for the entire population any more than a woman wearing a calico bonnet in Colonial Williamsburg is a typical American. But his headdress is an amazing heirloom, a thing of beauty deeply linked to an ancient way of life.

At the other end of the spectrum is the underworld of Port Moresby, the capital, a city plagued by carjackings and other street crimes. Many of the perpetrators are young men who left the countryside in search of work, only to end up unemployed and living desperately in grim settlements. Sandro’s pictures of them reveal a combination of fierceness and vulnerability that is downright poignant.

Then there are the women Sandro photographed. They toil on the other side of the world, but they’re familiar—one stooping under her burden, another smiling with a youngster on her hip. These women don’t represent PNG. They represent humanity. They’re us.

IN LIVING COLOR

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/23/3e/233ee188-1970-4b95-b6dd-52aef9a1c788/mar2018_d05_pngphoto.jpg)

The red and yellow face paint worn by this man from Jiwaka Province is made from colored rock. The black is a mixture of charcoal and pig fat. The white is traditionally made from clay, but nowadays correction fluid is often swapped in since it’s longer-lasting and comes with a handy application brush.

UNDER THE GUN

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/30/d4/30d44efa-ed46-42b6-a68d-aa228d5b0d2f/mar2018_d06_pngphoto.jpg)

A 27-year-old from the town of Baimuru holds up his homemade 9mm welded together from scrap metal. PNG’s street criminals, dubbed “raskols” in the 1970s, often carry makeshift weapons to intimidate victims during robberies and carjackings. If he were to fire this gun, it would likely injure him along with his target.

COMMON THREADS

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/51/10/511074db-e594-4874-b293-cdc0b9ffa08e/mar2018_d09_pngphoto.jpg)

Thressia Wapi, 40, carries bananas to market through the town of Ambunti. Her T-shirt features Port Vila, the capital of the neighboring nation Vanuatu. Handmade bilum bags like the one she’s carrying are traditionally woven from plant fibers. Those made from store-bought yarn are seen as status symbols.

SKIN AND BONES

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/70/a5/70a5aa3a-f086-47f1-a315-36861a30b7e8/mar2018_d01_pngphoto.jpg)

Boi Mark, 36, wears the traditional makeup of the Omo Masalai “Skeleton Men.” His wooden sword is used for a performance called a sing-sing, in which Omo Masalai members chase a fellow tribe member who is dressed as a piglike monster. The dance concludes when the warriors pretend to slay the beast.

OUT OF WHOLE CLOTH

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/0e/ea/0eea7bef-748e-4372-8a1c-ffca68187c81/mar2018_d10_pngphoto.jpg)

Nellie Gowey, 32, carries her son to the annual Crocodile Festival on the Sepik River. Clothing like hers is bought in town and often supplied by missionaries, who frown upon grass skirts. Grass, however, can be easily replaced, while cloth must be washed in muddy rivers that are inhabited by crocodiles.

BY THE SWORD

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/8a/20/8a20fd09-662b-4d04-8e47-825bffb013b6/mar2018_d04_pngphoto.jpg)

A 29-year-old from Central Province says he carries a machete rather than a gun because it’s easier to use with one hand. He claims to have lost his hand in a fight, and taken part in rapes and murders, but such assertions are hard to verify. Street criminals are seldom arrested by the country’s overwhelmed police forces.

OUTFITTED BY NATURE

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/99/de/99de2118-674a-449b-ac9c-d8cf15dbcf32/mar2018_d08_pngphoto-wr.jpg)

Joseph Kayan, a Goroka Show participant from Chimbu Province, wears boar tusks and the tail of a tree kangaroo around his neck. The design of his headdress is specific to his village: it includes bird-of-paradise feathers, with reeds to fill out the shape. His armlets hold sprigs of plants from his region.

SHELLING OUT WEALTH

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/77/ec/77ec7c3c-7d41-484f-8a20-ba2af7068233/mar2018_d02_pngphoto.jpg)

Regina Richard, 45, wears an heirloom headdress with feathers taken from peacocks and birds-of-paradise. The kina shells on her necklace are a status symbol. Shells were legal currency in Papua New Guinea until 1933, and they’re still used to purchase brides and settle blood feuds. The local currency is still called the kina.

MUD MEN

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/f8/fe/f8fe0823-6615-4d18-9a1c-d2bfcf699315/mar2018_d12_pngphoto.jpg)

Ninive Lefa, 19, wears the distinctive mud mask and bamboo finger extensions of the Asaro Mudman costume. Legend holds that the disguise originated after a clan from Asaro village suffered defeat from an enemy tribe wanting to steal their pigs. The surviving warriors fled into the Asaro River and emerged at dusk completely covered in mud.

STRONG COFFEE

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/a6/96/a6961ac7-a13b-4c0f-bd6c-29754114d1af/mar2018_d11_pngphoto.jpg)

Sani Pui, 58, works at the Monpi Coffee Exports factory. PNG produces around 800,000 60-kilo bags of coffee each year. The Monpi factory has an automated machine that can do the women’s sorting tasks more quickly, but the factory’s management fears that the local men would revolt if their wives were laid off.

GET UP, STAND UP

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/1f/10/1f10950f-cf08-46fc-904b-534f2e94acd8/mar2018_d03_pngphoto.jpg)

A 29-year-old in Port Moresby holds up his left hand, explaining that his ring finger was sliced off during a fight with a rival. Street criminals in PNG often signal their rebel status by wearing Bob Marley T-shirts or red, yellow and green accessories, even though they don’t follow any Rastafarian practices.

RITES OF PASSAGE

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/8f/2c/8f2ce85c-c1e9-4716-a78c-5e48c105f225/mar2018_d15_pngphoto.jpg)

Hodley Nau, 20, shows off initiation scars that resemble the ridges on the back of a crocodile. The scars, which represent the Sepik people’s reverence for the river creature, run from the shoulder to the hip and are made by rubbing ash into fresh cuts. Hodley wears foliage briefs known locally as “arse grass.”

UNDERGROUND THEATER

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/b3/a6/b3a669a2-0098-41d2-9a48-ef98179032d3/mar2018_d13_pngphoto.jpg)

David Gowep, 64, holds the head of a costume used to dramatize an ancient legend. His group, the Wanie people, believe a wild boar called Jambuis led their ancestors into the daylight after they had lived underground for some 300 years. David’s legs are clad in mud-soaked cloth to represent these subterranean origins.

RIVER DWELLERS

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/50/b0/50b0529d-ce9c-4d51-b4d3-9612d41b6f21/mar2018_d14_pngphoto.jpg)

During the annual Crocodile Festival held near the Sepik River in August, Anna Limo carries a live saltwater crocodile with its mouth held closed by a rubber band. The Sepik people use crocodiles for food, clothing, decoration, spiritual practices and tourism draws. There are no alligators in Papua New Guinea.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.