Mining the Mountains

Explosives and machines are destroying Appalachian peaks to obtain coal. In a West Virginia town, residents and the industry fight over a mountain’s fate

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Hobet-21-mine-West-Virginia-631.jpg)

Editor's Note -- On April 1, 2010, the Environmental Protection Agency released new guidelines on mountaintop mining. For more on this update, check out our Surprising Science blog.

For most of its route through the hardscrabble towns of West Virginia's central Appalachian highlands, U.S. Highway 60 follows riverbanks and valleys. But as it approaches Gauley Mountain, it swoops dramatically upward, making switchbacks over steep wooded ridges. It goes by the Mystery Hole, a kitschy tourist stop that claims to defy the law of gravity. Then the road abruptly straightens and you're in Ansted, a town of about 1,600 people. There's an auto dealership, an Episcopal church and a Tudor's Biscuit World restaurant. A historical marker notes that Stonewall Jackson's mother is buried in the local cemetery, and there's a preserved antebellum mansion called Contentment.

The tranquillity belies Ansted's rough-and-tumble history as a coal town—and the conflict now dividing its townspeople. Founded as a mining camp in the 1870s by English geologist David T. Ansted, the first person to discover coal in the surrounding mountains, it played an important part in the Appalachian coal economy for nearly a century. The coal baron William Nelson Page made Ansted his headquarters. You get a feeling for the old connection to coal in the one-room town museum behind the storefront that serves as the town's city hall, with its vintage mining helmets and pickaxes, company scrip and photographs of dust-covered miners. But beginning in the 1950s, the boom ended, and one by one the mine shafts closed, leaving most of the local populace feeling bitter and abandoned.

"They burned the buildings down and left the area," Mayor R. A. "Pete" Hobbs recalled of the coal companies' abrupt departure. "Unemployment when I graduated high school"—in 1961—"was 27 percent."

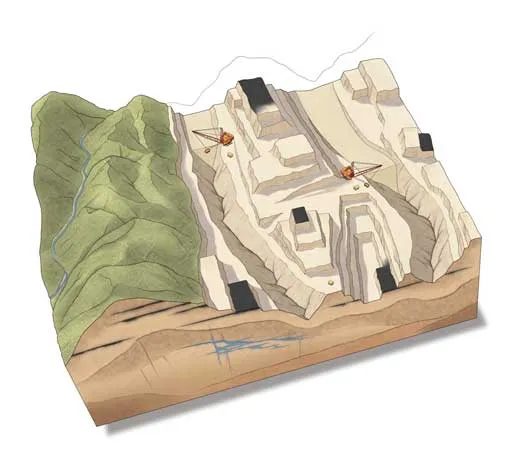

Now coal is back, with a different approach: demolishing mountains instead of drilling into them, a method known as mountaintop coal removal. One project is dismantling the backside of Gauley Mountain, the town's signature topographical feature, methodically blasting it apart layer by layer and trucking off the coal to generate electricity and forge steel. Gauley is fast becoming a kind of Potemkin peak—whole on one side, hollowed out on the other. Some Ansted residents support the project, but in a twist of local history, many people, former miners included, oppose it, making the town an improbable battleground in the struggle to meet the nation's rising energy needs.

Since the mid-1990s, coal companies have pulverized Appalachian mountaintops in West Virginia, Kentucky, Virginia and Tennessee. Peaks formed hundreds of millions of years ago are obliterated in months. Forests that survived the last ice age are chopped down and burned. The Environmental Protection Agency estimates that by 2012, two decades of mountaintop removal will have destroyed or degraded 11.5 percent of the forests in those four states, an area larger than Delaware. Rubble and waste will have buried more than 1,000 miles of streams.

This is devastation on an astonishing scale, and though many of us would like to distance ourselves from it, blaming it on others' callousness or excesses, mountaintop coal removal feeds the global energy economy in which we all participate. Even as I was writing this article at home in suburban Washington, D.C., it occurred to me that the glowing letters on my laptop might be traceable to mountaintop removal. An EPA Web site indicates that utlities serving my ZIP code get 48 percent of their power from coal—as it happens, the same portion of coal-generated electricity nationwide. In fact, the environmental group Appalachian Voices produced a map indicating 11 direct connections between West Virginia mountaintop coal sources and electric power plants in my area, the closest being the Potomac River Generating Station in Alexandria, Virginia. So coal torn from a West Virginia mountain was put on a truck and then a rail car, which took it to Alexandria, where it was incinerated, creating the heat that drove the turbines that generated the electricity that enabled me to document concerns about the destruction of that very same American landscape.

Demand for mountaintop coal has been rising quickly, driven by high oil prices, energy-intensive lifestyles in the United States and elsewhere and hungry economies in China and India. The price of central Appalachian coal has nearly tripled since 2006 (the long-term effect on coal pricing of the latest global economic downturn isn't yet known). U.S. coal exports increased by 19 percent in 2007 and were expected to go up by 43 percent in 2008. Virginia-based Massey Energy, responsible for many of Appalachia's mountaintop projects, recently announced plans to sell more coal to China. As demand increases, so does mountaintop removal, the most efficient and most profitable form of coal mining. In West Virginia, mountaintop removal and other kinds of surface mining (including highwall mining, in which machines demolish mountainsides but leave peaks intact) accounted for about 42 percent of all coal extracted in 2007, up from 31 percent a decade earlier.

Whether demand for coal will grow or shrink in the Barack Obama administration remains to be seen; as a candidate, Obama backed investing in "clean coal" technology, which would capture air pollutants from burning coal—especially carbon dioxide, linked to global warming. But such technologies are still experimental, and some experts believe they are unworkable. Former Vice President Al Gore, writing in the New York Times after the November election, said the coal industry's promotion of "clean coal" was a "cynical and self-interested illusion."

In Ansted, the conflict over mountaintop removal has taken on special urgency because it's about two competing visions for Appalachia's future: coal mining, West Virginia's most hallowed industry, and tourism, its most promising emerging business, which is growing at about three times the rate of the mining industry statewide. The town and its mining site lie between two National Park Service recreational areas, along the Gauley and New rivers, about ten miles apart. The New River Gorge Bridge, a span 900 feet above the water and perhaps West Virginia's best-known landmark, is just 11 miles by car from Ansted. Hawks Nest State Park is nearby. Rafting, camping—and, one day a year, parachuting from the New River Bridge—draw hundreds of thousands of people to the area annually.

Mayor Hobbs is Ansted's top tourism booster, a position he came to by a circuitous route. With no good prospects in town, he got a job in 1963 with C&P Telephone in Washington, D.C. Thirty years later, after a telecommunications career that took him to 40 states and various foreign countries, he returned to Ansted in one of AT&T's early work-from-home programs. He retired in 2000 and became mayor three years later, with ambitious tourism-development plans. "We're hoping to build a trail system to connect two national rivers together, and we'd be at the center of that—hunting, fishing, biking, hiking trails. The town has embraced that," Hobbs told me in his office, which is festooned with trail and park maps. What happens if the peak overlooking Ansted becomes even more of a mountaintop removal site? "A lot of this will be lost. 1961 is my reference point. [Coal companies] went away and left only a cloud of dust behind, and it's my fear that that's what will happen again with mountaintop removal."

Follow one of the old mining roads toward the top of Ansted's 2,500-foot ridge and the picturesque view changes startlingly. Once the road passes the crest, the mountain becomes an industrial zone. On the day that I visited, countless felled trees were scattered across a slope stripped clear by bulldozers. Such timber is sometimes sold, but the trees are more often burned—a practice that amplifies coal's considerable impact on air pollution and global warming, both by generating carbon dioxide and by eliminating living trees, which absorb atmospheric carbon dioxide. Half a mile beyond that treeless slope, a mountain peak had been rendered like a carcass in a meat factory: its outermost rock layers had been blasted away, the remains dumped in nearby hollows, creating "valley fills." Heavy earth-moving equipment had scraped out the thin layers of coal. A broad outcropping of pale brown rock remained, scheduled for later demolition.

The scale of these projects is best appreciated from above, so I took a flight over the coal fields in a small plane provided by Southwings, a conservation-minded pilots' cooperative. The forest quickly gave way to one mining operation, then another—huge quarries scooped out of the hills. Some zones sprawl over dozens of square miles. Explosives were being set in one area. In another, diggers were scraping off layers of soil and rock—called "overburden"—on top of the coal. Trucks were carting rock and gravel to dump in adjacent valleys. Black, shimmering impoundments of sludge stretched along hillsides. Tanker trucks sprayed flattened hills with a mixture of grass seed and fertilizer, which would give rise to a sort of artificial prairie where forested peaks had been.

I've reported on devastation around the world—from natural disasters such as Hurricane Katrina, to wars in Central America and the Middle East, to coastlines in Asia degraded by fish farming. But in the sheer audacity of its destruction, mountaintop coal removal is the most shocking thing I've ever seen. Entering a mountaintop site is like crossing into a war zone. Another day, as I walked near a site on Kayford Mountain, about 20 miles southwest of An-sted, along a dirt road owned by a citizen who declined to lease to the mining companies, a thunderous boom rattled the ground. A plume of yellow smoke rose into the sky, spread out and settled over me, giving the bare trees and the chasm beyond the eerie cast of a battlefield.

To an outsider, the process may seem violent and wasteful, with a yield that can equal only about 1 ton of coal per 16 tons of overburden. But it's effective. "With mountaintop removal you're able to mine seams that you could not mine with underground mining because they are so thin—but it's a very high-quality coal," said Roger Horton, a truck driver and United Mine Workers Union representative who works at a mountaintop site in Logan, West Virginia. Mountaintop operations can mine seams less than two feet deep. "No human being could burrow into a hole 18 inches thick and extract the coal," Horton said. Typically, he adds, a project descends through seven seams across 250 vertical feet before reaching a layer of the especially high-grade coal that is used (because of the extreme heat it generates) in steel manufacturing. After that's collected, it's on to the next peak.

The Appalachian coal fields date back about 300 million years, when today's green highlands were tropical coastal swamps. Over the millennia, the swamps swallowed up massive amounts of organic material—trees and leafy plants, animal carcasses, insects. There, sealed off from the oxygen essential to decomposition, the material congealed into layers of peat. When the world's landmasses later collided in a series of mega-crashes, the coastal plain was pushed upward to become the Appalachians; after the greatest of these collisions, they reached as high as today's Himalayas, only to be eroded over the ages. The sustained geologic pressure and heat involved in creating the mountains baked and compressed the peat from those old bogs into seams of coal from a few inches to several feet thick.

First mined in the 19th century, Appalachian coal dominated the U.S. market for 100 years. But the game changed in the 1970s, when mining operations started in Wyoming's Powder River Basin, where coal seams are far thicker—up to 200 feet—and closer to the surface than anything in the East. It was in the West and Midwest where miners first employed some of the world's largest movable industrial equipment to scrape the earth. Behemoths called draglines can be more than 20 stories tall and use a scoop big enough to hold a dozen small cars. They are so heavy that no onboard power source could suffice—they tap directly into the electrical grid. Western mining operations achieved fantastic economies of scale, though Western coal has a lower energy content than Eastern coal and costs more to move to its principal customers, Midwestern and Eastern power plants.

Then, in 1990, Eastern coal mining, long in decline, got a boost from an unlikely source: the Clean Air Act, revised that year to restrict sulfur dioxide emissions, the cause of acid rain. As it happens, central Appalachia's coal deposits are low in sulfur. Soon the draglines arrived in the East and coal mining's effect on the landscape took an ugly turn. To be sure, Wyoming's open-pit coal mines aren't pretty, but their location in a remote, arid basin has minimized the impact on people and wildlife. By contrast, coal seams in Appalachia require extensive digging for a smaller yield. The resulting debris is dumped into nearby valleys, effectively doubling the area of impact. More people live near the mines. And the surrounding forests are biologically dense—home to a surprising abundance and variety of life-forms.

"We are sitting in the most productive and diverse temperate hardwood forest on the planet," said Ben Stout, a biologist at Wheeling Jesuit University, in West Virginia's northern panhandle. We were on a hillside a few miles from his office. "There are more kinds of organisms living in the southern Appalachians than in any other forest ecosystem in the world. We have more salamander species than any place on the planet. We have Neotropical migratory birds that come back here to rest and nest. They are flying back up here as they have over the eons. That relationship has evolved here because it's worth it to them to travel a couple of thousand miles to nest in this lush forest that can support their offspring in the next generation."

Stout has spent the past decade studying the effects of mining on ecosystems and communities. We waded into a chilly stream, about three feet across, that ran over stones and through clots of rotting leaves. He bent down and started pulling wet leaves apart, periodically flicking squirming bugs into a white plastic strainer he'd placed on a rock. Stoneflies were mating. A maggot tore through the layers of packed leaves. Other, smaller larvae were delicately peeling the outermost layer off one leaf at a time. This banquet, Stout said, is the first link in the food chain: "That's what drives this ecosystem. And what happens when you build a valley fill and bury this stream—you cut off that linkage between the forest and the stream."

Normally, he went on, "those insects are going to fly back into the woods as adults, and everybody in the woods is going to eat them. And that happens in April and May, at the same time you have the breeding birds coming back, the same time the turtles and toads are starting to breed. Everything is coming back in around the stream because that's a tremendously valuable food source."

But a stream buried beneath a valley fill no longer supports such life, and the effects reverberate through the forest. A recent EPA study showed that mayflies—among the most fecund insects in the forest—had largely disappeared from waterways downstream from mountaintop mining sites. That might seem a small loss, but it's an early, critical break in the food chain that, sooner or later, will affect many other animals.

Mountaintop mining operations, ecologists say, fracture the natural spaces that enable dense webs of life to flourish, leaving smaller "islands" of unspoiled territory. Those become biologically impoverished as native plants and animals die and invasive species move in. In one study, EPA and U.S. Geological Survey scientists who analyzed satellite images of a 19-county area in West Virginia, eastern Kentucky and southwestern Virginia found that "edge" forests were replacing denser, greener "interior" forests far beyond the mountaintop mining-site borders, degrading ecosystems across a wider area than previously thought. Wildlife is in decline. For instance, cerulean warblers, migratory songbirds that favor Appalachian ridgelines for nesting sites, have dropped 82 percent over the past 40 years.

The mining industry maintains that former mining sites can be developed commercially. The law requires that the mining company restore the mountaintop's "approximate original contour" and that it revert to forestland or a "higher and better use." A company can get an exemption from the rebuilding requirement if it shows that a flattened mountain may generate that higher value.

Typically, mining companies bulldoze a site and plant it with a fast-growing Asian grass to prevent erosion. One former surface mine in West Virginia is now the site of a state prison; another is a golf course. But many reclaimed sites are now empty pasturelands. "Miners have claimed that returning forestland to hay land, wildlife habitat or grassland with a few woody shrubs on it was ‘higher use,'" says Jim Burger, a professor of forestry at Virginia Tech. "But hay land and grassland is almost never used for that [economic] purpose, and even wildlife habitat has been abandoned."

Some coal companies do rebuild mountains and replant forests—a painstaking process that takes up to 15 years. Rocky Hackworth, the superintendent of the Four Mile Mine in Kanawha County, West Virginia, took me on a tour of rebuilding efforts he oversees. We climbed into his pickup truck and rolled across the site, past an active mine where half a hillside had been scooped out. Then the twisting dirt road entered an area that was neither mine nor forest. Valley fills and new hilltops of crushed rock had been covered with topsoil or "topsoil substitute"—crushed shale that can support tree roots if loosely packed. Some slopes had grass and shrubs, others were thick with young sumacs, poplars, sugar maples, white pines and elms.

This type of reclamation requires a degree of stewardship many mine companies have not provided, and its long-term ecological impact isn't clear, especially given the stream disruptions caused by valley fills. And it still faces regulatory hurdles. "The old mind-set is, we've got to control erosion first," Hackworth said. "So that's why they want it walked real good, packed real good. You plant grass on it—which is better for controlling erosion, but it's worse for tree growth. It's a Catch-22."

Some landowners have made stabs at creating wildlife habitats at reclaimed sites with pools of water. "The small ponds are marketed to the regulatory agencies as wildlife habitat, and ducks and waterfowl do come in and use that water," said Orie Loucks, a retired professor of ecology at Miami University of Ohio who has studied the effects of mountaintop removal. "It's somewhat enriched in acids, and, of course, a lot of toxic metals go into solution in the presence of [such] water. So it's not clear the habitat is very healthy for wildlife and it's not clear many people go up on these plateau areas to hunt ducks in the fall."

Mountaintop mining waste contains chemical compounds that otherwise remain sealed up in coal and rock. Rainwater falling on a valley fill becomes enriched with heavy metals such as lead, aluminum, chromium, manganese and selenium. Typically, coal companies construct filtration ponds to capture sediments and valley-fill runoff. But the water flowing out of these ponds isn't pristine, and some metals inevitably end up flowing downstream, contaminating water sources.

Mountaintop sites also create slurry ponds—artificial lakes that hold the byproducts of coal processing and that sometimes fail. In 2000, a slurry impoundment in Kentucky leaked into an underground mine and from there onto hillsides, where it enveloped yards and homes and spread into nearby creekbeds, killing fish and other aquatic life and contaminating drinking water. The EPA ranked the incident, involving more than 300 million gallons of coal slurry, one of the worst environmental disasters in the southeastern United States. After a months-long cleanup, federal and state agencies fined the impoundment owner, Martin County Coal, millions of dollars and ordered it to close and reclaim the site. Officials at the U.S. Mine Safety and Health Administration later conceded that their procedures for approving such sites had been lax.

Scientists and community groups are concerned about the possible effects of coal-removal byproducts and waste. Ben Stout, the biologist, says he has found barium and arsenic in slurry from sites in southwestern West Virginia at concentrations that nearly qualify as hazardous waste. U.S. Forest Service biologist A. Dennis Lemly found deformed fish larvae in southern West Virginia's Mud River—some specimens with two eyes on one side of their head. He blames the deformities on high concentrations of selenium from the nearby Hobet 21 mountaintop project. "The Mud River ecosystem is on the brink of a major toxic event," he wrote in a report filed in a court case against the mining site, which remains active.

Scientists say they have little data on the effects of mountaintop coal mining on public health. Michael Hendryx, a professor of public health at West Virginia University, and a colleague, Melissa Ahern of Washington State University, analyzed mortality rates near mining-industry sites in West Virginia, including underground, mountaintop and processing facilities. After adjusting for other factors, including poverty and occupational illness, they found statistically significant elevations in deaths for chronic lung, heart and kidney disease as well as lung and digestive-system cancers. Overall cancer mortality was also elevated. Hendryx stresses that the information is preliminary. "It doesn't prove that pollution from the mining industry is a cause of the elevated mortality," he says, but it appears to be a factor.

Mountaintop removal has done what no environmental group could ever do: it has succeeded in turning many local people, including former miners, against West Virginia's oldest industry. Take 80-year-old Jim Foster, a former underground miner and mine-site welder and a lifelong resident of Boone County, West Virginia. As a boy before World War II, he used to hike and camp in Mo's Hollow, a small mountain valley now filled with rubble and waste from a mountaintop removal site. Another wilderness area he frequented, a stream valley called Roach Branch, was designated in 2007 as a fill site. Foster joined a group of local residents and the Huntington, West Virginia-based Ohio Valley Environmental Coalition in a federal lawsuit to block the Roach Branch Valley fill site on the grounds that the environmental impacts hadn't been adequately assessed. They won the first round when Judge Robert Chambers issued a temporary restraining order against the valley fills. The coal company is appealing the decision.

Foster says he puts up with a daily barrage of irritations from nearby mountaintop removal projects: blasting, 22-wheeled coal trucks on the road and ubiquitous dust. As we talked in his living room, trucks carrying coal explosives rumbled by. "Practically every day, our house is shook by the violent tremors caused by these blasts," he said, gesturing from his easy chair. "The one up there—you can see it from my window here—I've watched it as they tore that down. Before they started on it, it was beautiful twin peaks there, it was absolutely beautiful. And to look out and see the destruction going on day to day like it has, and see that mountain disappear, each day more of it being gone—to me that really, really hurts."

Around mining sites, tensions run high. In Twilight, a Boone County hamlet situated among three mountaintop sites, Mike Workman and his next-door neighbor, another retired miner named Richard Lee White, say they have battled constantly with one nearby operation. Last year, trucks exiting the site tracked onto the road a mud slick that persisted for weeks and precipitated several accidents, including one in which Workman's 27-year-old daughter, Sabrina Ellsworth, skidded and totaled her car; she was shaken up but not injured. State law requires that mining operations have working truck washes to remove mud; this one did not. After Workman complained repeatedly to state agencies, the state Department of Environmental Protection shut down the mine and fined its owner $13,482; the mine reopened two days later, with a working truck wash.

Workman also remembers when a coal slurry impoundment failed in 2001, sending water and sludge pouring through a hollow onto Route 26. "When it broke loose it come down, and my daughter lived at the mouth of it. The water was plumb up in her house past her windows, and I had to take a four-wheel-drive truck to get her and her kids. And my house down here, [the flood] destroyed it."

Ansted residents have had mixed success fighting a mining operation conducted by the Powellton Coal Company outside town. In 2008, they lost an appeal before West Virginia's Surface Mine Board, which rejected their argument that the blasting could flood homes by releasing water sealed in old mine shafts. But the year before, the town beat back an attempt to run big logging and coal trucks past a school and through town. "This is a residential area—this is not an industrial area," says Katheryne Hoffman, who lives at the edge of town. "We managed to get that temporarily stopped—but then they still got the [mining] permit, which means they will begin to bring the coal through somewhere, and it'll be the path of least resistance. Communities have to fight for their lives to get this stopped." A Powellton Coal Company official did not respond to requests for comment.

But many residents support the industry. "You have people who don't realize it is our livelihood here—it always has been, always will be," says Nancy Skaggs, who lives just outside Ansted. Her husband is a retired miner and her son does mine-site reclamation work. "Most of those against [mining] are people who have moved into this area. They don't appreciate what the coal industry does for this area. My husband's family has been here since before the Civil War, and always in the coal industry."

The dispute highlights the town's—and state's—predicament. West Virginia is the nation's third-poorest state, above only Mississippi and Arkansas in per capita income, and the poverty is concentrated in the coal fields: in Ansted's Fayette County, 20 percent of the population lives below the poverty line, compared with 16 percent in the state and 12 percent nationwide. For decades, mining has been the only industry in dozens of small West Virginia towns. But mountaintop coal removal, because of the toll it takes on the natural surroundings, is threatening the quality of life in communities that the coal industry helped build. And mountaintop removal, which employs half as many people to produce the same amount of coal as an underground mine, doesn't bring the same benefits that West Virginians once reaped from traditional coal mining.

The industry dismisses opponents' concerns as exaggerated. "What [environmentalists] are attempting to do is stir the emotions of people," says Bill Raney, president of the West Virginia Coal Association, "when the facts are that the disturbance is limited, and the type of mining is controlled by the geology."

West Virginia's political establishment has been unwavering in its support for the coal industry. The close relationship is on display every year at the annual West Virginia Coal Symposium, where politicians and industry insiders mingle. This past year, Gov. Joe Manchin and Senator Jay Rockefeller addressed the gathering, advocating ways to turn climate-change legislation to the industry's advantage and reduce its regulatory burdens. "Government should be your ally, not your adversary," Manchin told coal-industry representatives.

Without such backing, mountaintop removal would not be possible, because federal environmental laws would prohibit it, says Jack Spadaro, a former federal mining regulator and a critic of the industry. "There is not a legal mountaintop mining operation in Appalachia," he says. "There literally is not one in full compliance with the law."

Since 1990, U.S. policy under the Clean Water Act has been "no net loss of wetlands." To "fill" a wetland, one needs a permit from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, which is supposed to evaluate the environmental effects and require mitigation by creating new wetlands elsewhere. If the potential impact is serious enough, the National Environmental Policy Act kicks in and a detailed study must be done. But the coal-mining industry has often obtained the necessary dumping permits without due consideration of possible environmental impacts.

The Corps has admitted as much in response to lawsuits. In one case, the Corps said it probably shouldn't even be overseeing such permits because the dumped waste contained polluting chemicals regulated by the EPA. In another case, brought by West Virginia environmental groups against four Massey Energy mining projects, the Corps conceded that it routinely grants dumping permits with virtually no independent study of the possible ecological fallout, relying instead on the assessments that coal companies submit. In a 2007 decision in that case, Judge Chambers found that "the Corps has failed to take a hard look at the destruction of headwater streams and failed to evaluate their destruction as an adverse impact on aquatic resources in conformity with its own regulations and policies." But because three of the mining projects challenged in that case were already underway, Chambers allowed them to continue, pending the case's resolution. Massey has appealed the case to the Virginia-based United States Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit, which has overturned several lower court rulings that went against mining interests.

In 2002, the Bush administration rewrote the rule defining mountaintop mining waste in an attempt to work around the legal ban on valley fills. This past October, the Interior Department, pending EPA approval, did away with regulations that ban dumping mine waste within 100 feet of a stream—a rule that's already routinely ignored (though the EPA recently fined Massey Energy $20 million for violations of the Clean Water Act).

Industry critics say they're also hampered by West Virginia regulations that protect private interests. The vast majority of West Virginia acreage is owned by private landholding companies that lease it and the mineral rights to coal companies. And while industrial land-use planning is a matter of public record in most states, not so in West Virginia. As a result, critics say, mountaintop projects unfold slowly bit by bit, making it hard for outsiders to grasp a project's scale until it's well underway.

In Ansted, residents say they can't even be sure what's coming next because the coal company doesn't explain its plans. "They will seek permits on small plots, 100- to 300-acre parcels," said Mayor Hobbs. "My sense is, we should have a right to look at that long-range plan for 20,000 acres. But if we got to see the full scope of those plans, then mountaintop removal would stop," because the enormousness of the affected areas would stoke opposition.

The standoff is frustrating to Hobbs, who has been unable to reconcile the coal industry's actions with his town's ambitions. "I'm a capitalist," he said. "I worked for a major corporation. I'm not against development. It's troubling—I see tourism and economic quality of life as the only thing that will last beyond a 15- to 20-year economic cycle. And with mountaintop removal, that is at risk. And even if we dodge that bullet, the next community may not."

John McQuaid lives in Silver Spring, Maryland, and is the co-author of Path of Destruction: The Devastation of New Orleans and the Coming Age of Superstorms.