Monkey in the Middle

Blamed for destroying one of North Africa’s most important forests, Morocco’s Barbary macaques struggle to survive

High in the atlas mountains of morocco an important ecological drama is playing out, with the future of North Africa’s largest intact forest and the welfare of many Moroccans at stake. Like nearly all eco-dramas, this one has an embattled, misunderstood protagonist and enough conflict and blame to fill a Russian novel. It’s also a reminder of nature’s delicate interconnectedness— a parable of how the destruction of one natural resource may eventually cause large and untoward harm to people, among other interesting life-forms.

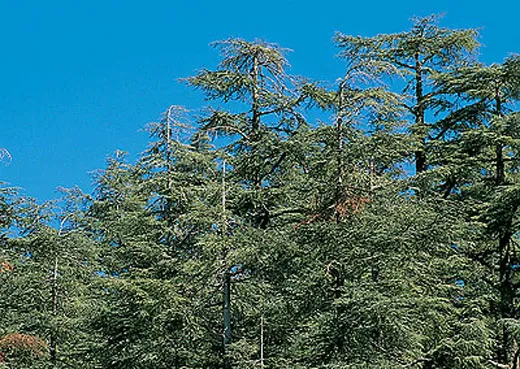

Ranging through the mountains— which protect Casablanca, Marrakesh and other cities along Morocco’s northern coastal plain from the Sahara—are vital forests of oak and cedar. The forests capture rain and snow blowing in from the Atlantic Ocean, and the precipitation feeds underground water sources, or aquifers, that in turn supply water for many Moroccan crops. The problem is that trees have begun dying at an alarming rate, and meanwhile the water table is decreasing, crops have been threatened and the Sahara’s reach has expanded.

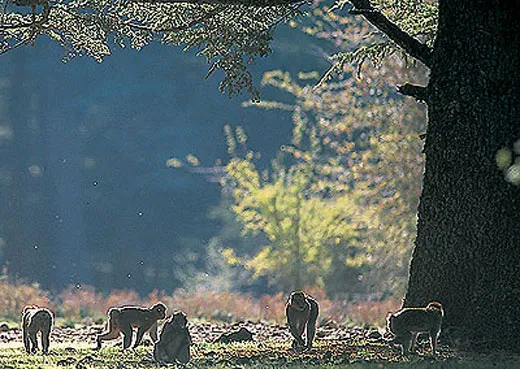

The leading protagonist in this drama is the Barbary macaque (Macaca sylvanus), a medium-sized monkey found only in Morocco, Algeria and Gibraltar and also known as the Barbary ape for its resemblance to its larger, also tailless, cousin. The Barbary macaque is one of 20 species of macaque, which inhabit a greater variety of the world’s habitats and climates than any other primate except human beings. In Morocco, which has been beset by drought for at least a decade, officials largely blame macaques for killing the Middle Atlas forest, because the animals are known to strip bark from cedar trees to get at the moist, nutrient-rich living tissue underneath. Though Barbary macaques have been designated as a vulnerable species by the World Conservation Union (IUCN), meaning the animal is at high risk of extinction in the wild in the not-too-distant future, some Moroccan officials dispute that the monkeys are scarce and have even considered relocating the animals to help save the forests. “The predators of the monkeys, like the panther and the lion, have been killed, and now we have too many monkeys,” says Ahmed Kaddaf, engineer-in-charge of the water and forests authority in Ain Leuh, a village adjacent to the Middle Atlas forest.

But an Italian scientist who has studied macaques in Morocco for 20 years says the monkeys have nothing to do with the deforestation. Andrea Camperio Ciani, 46, a primatologist at the University of Padua, says the monkeys have merely become “scapegoats for all that’s wrong in the area.” In fact, he argues that macaques are the victims of the dying forest, not the other way around; water and food shortages have played a large part in the animals’ decline, he says, from 40,000 to 6,000 nationwide in the two decades he has been studying them. Poaching has also taken a toll, he says; poachers sell the animals as pets to tourists for $65 to $115 each.

Camperio Ciani argues that Morocco’s cedar and oak forests are dying for a number of complex reasons, including logging, parasitic infestation and drought-in- duced tree diseases. Similarly, a fast-growing human population has strained scant water sources, with towns such as Ifrane, Azrou and Ain Leuh pumping water out of aquifers. In the past decade, the region’s water table has fallen 40 percent because of persistent drought conditions, according to Brahim Haddane, director of Morocco’s national zoo outside Rabat and an IUCN representative. In addition, commercial charcoal makers also harvest oak trees.

But the biggest problem, according to Camperio Ciani, is the herding practices of the area’s 750 Berber shepherds and their families. Not only do these semi-nomadic people herd their own goats, which are notoriously hard on vegetation, roots included, they also tend large flocks of sheep on behalf of absentee investors. In recent years, the region’s 1.5 million grazing sheep and goats have in places all but stripped the forest lands and environs of low-lying vegetation, says Haddane. Moreover, says Camperio Ciani, shepherds further contribute to deforestation by cutting low branches to provide fodder for their animals as well as heating and cooking fuel. In theory, the Moroccan government, which owns most of the Atlas Mountains forest, allows some logging but prohibits such branch cutting. Still, Camperio Ciani says that for a bribe of 1,000 dirhams or so (about $115) some forestry officials will look the other way. “These woods should have a thick underbrush for regeneration to take place and hold the soil,” he says, adding that without the underbrush, erosion turns the forest into a carpet of stones.

The director of the Conservation of Forestry Resources in Morocco, Mohamed Ankouz, says the forest is in decline because people are on the rise. “When we were 6 million people, the balance was right,” he said in an impromptu interview in Rabat in 2002. “Now with 30 million, we have quite a problem. And 10 million make a living, directly or indirectly, in or around the forest. We have had years of drought and the forest is very fragile, and the shepherd’s use of the land compromises regeneration.” Still, he added, the macaques are a problem and the government has considered moving them.

Camperio Ciani acknowledges that macaques strip bark from cedars but says that’s a desperate measure in response to drought conditions exacerbated by shepherds. Droughts during the 1990s prompted the shepherds to set up forest camps near springs visited by monkeys. Some shepherds built concrete enclosures around the springs, blocking the monkeys’ access to the water. Camperio Ciani says the macaques then turned to eating the tops of cedar trees to get at the cambium tissue underneath the bark to slake their thirst. “Making water more accessible to wild animals,” Camperio Ciani and co-workers wrote in the journal Conservation Biology, “might reduce bark-stripping behavior.” The scientists propose rigging the concrete wells with ladders to accommodate the monkeys. In any event, the monkeys don’t kill healthy trees, says Mohamed Mouna, of the Scientific Institute of the University Mohammed Vin Rabat. Most of the trees debarked by the macaques, he says, “are alive and well today.” Meanwhile, the IUCN, in response to a request from the Moroccan government, has agreed to help study Barbary macaques in the wild and, among other things, assess how the monkeys’ bark-stripping affects forest health.

Today’s field biologists not only have to study animals, but also delve into seemingly intractable social, economic and land issues. At a conference in Ifrane this past June, Camperio Ciani presented a forest restoration plan that involves raising the Berber’s standard of living, making residents more aware of deforestation, supporting eco-tourism and restricting absentee investments in sheep. Without these steps, the Moroccan eco-drama will have only one conclusion, he says: things will get far worse for macaques and humans alike “if the root causes of the environmental deterioration aren’t addressed.”