Multiple Concussions May Have Sped Hemingway’s Demise, a Psychiatrist Argues

The troubled author may have suffered from Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy, the disease that plagues modern football players

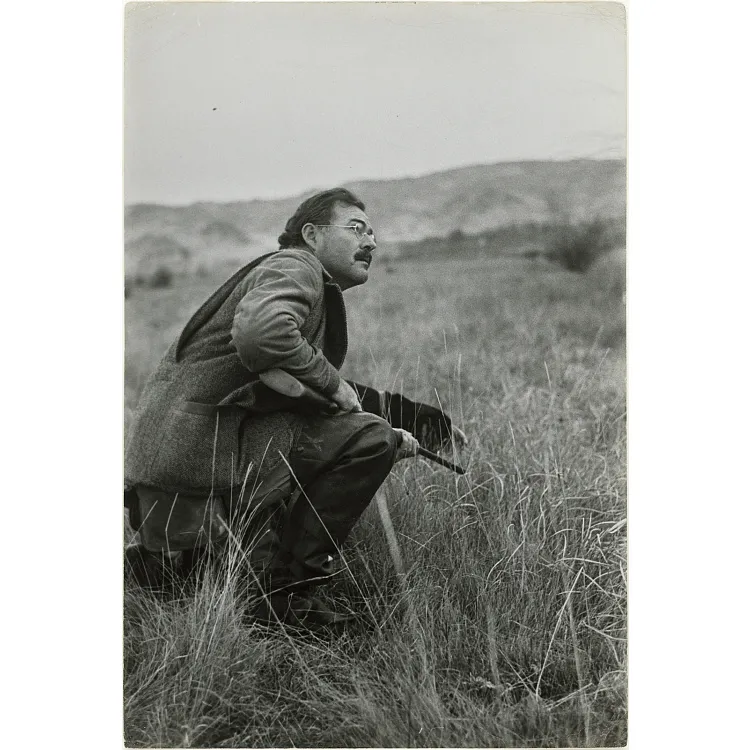

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/15/06/1506db9b-0b33-4512-8deb-9cd9cf47f1ac/1599px-ernest_hemingway_aboard_the_pilar_1935.png)

At the 1954 Award Ceremony for the Nobel Prize in literature, one thing was clear: This year's winner boasted a rather unusual CV. The author receiving this prestigious award was no mild-mannered writer, who had lived his life surrounded by a world of books.

"A dramatic tempo and sharp curves have also characterized (Ernest) Hemingway's own existence, in many ways so unlike that of the average literary man," said Swedish Academy Secretary Anders Österling in his presentation speech. "He also possesses a heroic pathos which forms the basic element in his awareness of life, a manly love of danger and adventure with a natural admiration for every individual who fights the good fight in a world of reality overshadowed by violence and death."

Indeed, Hemingway wasn't there that day to receive the award he had so "coveted," according to one biographer. Earlier that year, he and his wife had narrowly survived two plane crashes that led some papers to accidentally print the author's obituary and left Hemingway with serious injuries, including a skull fracture that caused cerebrospinal fluid to leak out of his ear. Hemingway spent much of the next seven years in poor health and writing little before infamously taking his own life in July 1961.

Scholars have long argued over what led Hemingway to this tragic conclusion—a debate that sometimes overshadows the legacy of his writings. Now, in a new book called Hemingway's Brain, North Carolina psychiatrist Andrew Farah asserts that these debilitating plane crashes caused what were merely the last in a series of concussions the author received during his turbulent life. In total, these blows caused him to suffer from Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy, a disease caused by the degeneration of a person's battered brain, Farah argues.

Farah's "diagnosis" could shed new light on a literary life often romanticized in terms of brash masculinity and decades of fighting, exploring and drinking. "His injuries and head traumas were frequent, random and damaging," Farah writes in his book, published this month by the University of South Carolina Press. "These repeated concussive blows did cumulative damage, so that by the time he was fifty his very brain cells were irreparably changed and their premature decline now programmed into his genetics."

Instead of searching for clues to Hemingway's psyche in the words of his stories as previous scholars have done, Farah drew instead on the extensive trove of letters Hemingway left behind, many of these have only recently been published in a project led by Hemingway’s surviving son. Farah also scoured memoirs from his friends and family, and even a file the FBI opened on him after the author attempted to spy on Nazi sympathizers in Cuba during World War II.

"It became an obsession," says Farah, who has been named a Distinguished Fellow of the American Psychiatric Association and lectured extensively on electroconvulsive therapy and CTE. "It didn't take long to connect the dots."

Doctors are currently working on developing methods to diagnose CTE before a person has died. But for now, a diagnosis still requires a thorough examination of dead brain tissue, points outsKevin Bieniek, a Mayo Clinic research fellow who works in the lab of neuropathologist Dennis Dickson. To conclusively determine whether or not a person had CTE, a pathologist must remove and preserve the brain of the dead person in question, cut it into thin slices and examine it for signs of the disease.

"Scholars can attest Ernest Hemingway participated in contact sports and sustained traumatic brain injuries during his life. Furthermore, paranoia and other psychiatric symptoms he exhibited in his final years have been described in individuals with traumatic encephalopathy syndrome," says Bieniek via email. However, "when one considers that CTE is a disorder that can only by accurately diagnosed through post-mortem autopsy ... a clinical diagnosis of CTE would still be largely speculative."

Farah, however, believes he's found the answer. "So many people got it so wrong," Farah says. Frustratingly for Farah, many biographers have echoed the "mythology" that Hemingway suffered and died as a result of his bipolar disorder, or that he succumbed solely to alcoholism. These conclusions miss key clues, Farah says, such as how Hemingway's condition actually worsened after receiving normally curative electroconvulsive therapy, a contradiction that inspired him to start writing his book.

"Patients that we give ECT to that deteriorate rather than improve usually have some organic brain disease that we have yet to diagnose," Farah says, meaning they suffer from a problem with the actual tissue of their brain rather than a problem with their mind. Instead of altering the brain chemistry in beneficial ways, electroconvulsive therapy will usually add more stress to these patients' already damaged brains, he says.

Through letters, eyewitness accounts and other records, Farah documented at least nine major concussions that Hemingway appears to have suffered during his life, from hits playing football and boxing, to shell blasts during World War I and II, to car and plane crashes.

Such a diagnosis would explain much of his behavior during the last decade of Hemingway’s life, Farah says. In his final years, he became a shadow of his former self: He was irrationally violent and irritable toward his long-suffering wife Mary, suffered intense paranoid delusions, and most devastatingly to the author, he lost the ability to write.

"Ernest spent hours every day with the manuscript of his Paris sketches—published as A Moveable Feast after his death—trying to write but unable to do more than turn its pages," his friend, writer A.E. Hotchner, recalled of Hemingway's final months in a New York Times opinion published 50 years after the author's death. When visiting Hemingway in the hospital, Hotchner asked his friend why he was saying he wanted to kill himself.

“What do you think happens to a man going on 62 when he realizes that he can never write the books and stories he promised himself?" Hemingway asked Hotchner. "Or do any of the other things he promised himself in the good days?" Hemingway killed himself with a shotgun the following month.

CTE was by no means the sole factor in Hemingway's suicide, Farah notes—Hemingway's alcoholism certainly played some role in his decline, and the author had struggled with depression since childhood. "The very tool that he needed to create these masterpieces was declining," Farah says of Hemingway's brain in these final years.

Moreover, Hemingway infamously came from a family rife with suicides; his father and several of his siblings and children ended up killing themselves. While the science is still unclear, researchers have identified some links between genetics and suicidal behavior. "He believed that he was the descendant of suicidal men on both sides of the family," Farah says. "I think there were some genetic underpinnings [to his suicide]."

Thanks to the growing awareness and study of CTE in recent years, largely driven by the epidemic of the disease among American football players, Farah says that Hemingway today would have likely been diagnosed much more accurately and received more helpful drugs and treatments, many of which he outlines in his book. "He thought he was permanently damaged," Farah says, but "we'd be very hopeful in his case."

Farah hopes his book will settle the debate about Hemingway's physical ailments so that future researchers can turn their efforts to examining the evolution and legacy of his writings. "I've talked about it in terms of hardware," Farah says. "I think the Hemingway scholars now can talk about it more in terms of software."

Yet one thing is clear to Farah: Hemingway will still be read and scrutinized long into the future.

"The man's popularity just grows," Farah says. "He just appeals to so many people."