Is the Mysterious Sea Cucumber Slipping Out of Our Grasp?

The slimy, tasty enigmas have long been over-harvested. An indigenous community in Canada could be close to finding a sustainable solution

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/38/14/38147c25-a1d2-4399-846d-1c19c88bd56f/gopr1966.jpg)

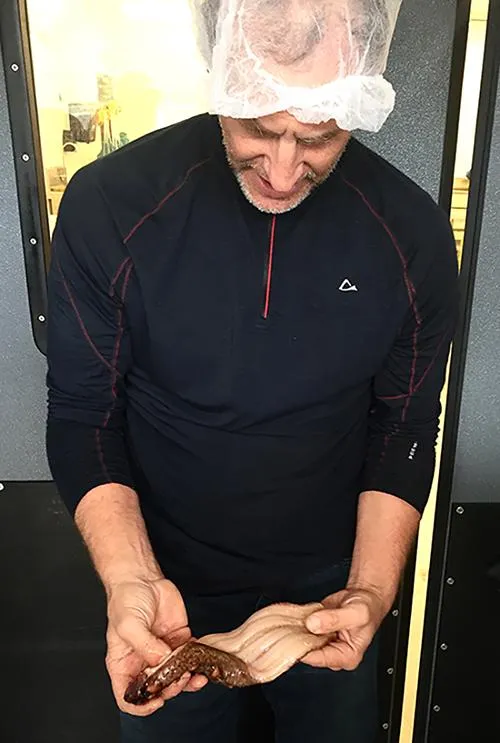

Larry Greba stood in front of the seafood processing facility with slime dripping from his fingers. Dangling across his two hands was a flat creature—the source of the slime. One side was all pink flesh, like a cartoonishly long tongue. The other bore tooth-like protuberances, called ossicles, above speckled reddish black skin. It would’ve been hard to say which end of the animal was the front if it weren't for the whiskery, tentacle-like mouth appendage hanging from one end.

At around a foot long, the dead sea cucumber looked something like a Lovecraftian sea monster. Only this particular monster happened to be edible, a delicacy even, and exorbitantly priced: sea cucumbers sell for around $16 per pound for the pink muscle, and $22 per pound for the lumpy skin. Not bad for something that eats dirty sand and spits out its guts when scared.

“It’s actually very tasty,” Greba said of the muscle, which he compared to the taste of clams. He uses the skin for seasoning soups and stir-fries, though what exactly the flavor was most similar to he couldn’t say.

Greba is the director of the Kitasoo Development Corporation, located in Klemtu, a 500-person indigenous town tucked up on the coast of British Columbia. The town is mainly populated by the Kitasoo/Xai’xais band, which formed in the 1860s when the two distinct nations (Kitasoo and Xai’xais) came together. That overcast September afternoon, Greba was demonstrating the sea cucumber cleaning process with a specimen from an experimental fishery—one set up and now maintained by the Kitasoo/Xai’xais band and commercial harvesters to study sustainable harvesting rates.

The slug-like animals are a staple part of the indigenous community’s diet, usually cooked by boiling them whole to soften the chewy flesh, then sometimes pan fried. But they’re also important economically: High demand for sea cucumbers in China, where the dried skins (called “beche-de-mer”) are used medicinally and the meat is considered a culinary delicacy, means the price for the product is correspondingly high—and ever increasing. Which has members of the indigenous community particularly worried about the fate of these strange echinoderms.

“Sea cucumbers are the second-most valuable seafood commodity that are exported from Pacific islands,” says fisheries scientist Hampus Eriksson on the podcast of the WorldFish Center, a global nonprofit he works for. And as the Chinese economy has grown, the boundaries of China’s demand have stretched far beyond what the fisheries within their borders can supply. In 2015, according to China Daily, Canada exported nearly a third of its harvest to China, with sea cucumbers coming from both the Atlantic and the Pacific coasts.

So far British Columbia’s stock is only “moderately exploited.” But that could soon change. “A lot of fisheries [in China] were not managed properly and they were driven to a point where they haven’t recovered, and may never recover,” Greba says. If British Columbia wants to avoid the same fate, experts say it’ll require regular monitoring, research, and cooperation between the government, the fishing industry and the First Nations.

The plight of sea cucumbers goes beyond Canada. Of the world’s 377 species, 66 are harvested regularly for food and medicine. Of those, 16 appear on the IUCN Red List for endangered species. Sea cucumber stocks have been decimated off the coasts of Costa Rica, Egypt, India, Panama, Papua New Guinea, Tanzania, Venezuela and Hawaii. A full 20 percent of fisheries have been totally depleted, while another 35 percent are overexploited, according to a 2011 report.

But when it comes to protecting these strange creatures, there’s a significant challenge: their biology is as alien as their appearance. For how little we know about them, they may as well be extra-terrestrials. We don’t know how long they live, how they move, or even how large they can get (scientists have seen them reach the size of a human arm). They’re slimy, tasty enigmas—and until scientists start answering some of the basic questions about their life cycles, their fate will remain as elusive as their physiology.

.....

The Kitasoo/Xai’xais have been eating giant red sea cucumbers, Parastichopus californicus, for centuries. They’re even credited with the animal’s origin story. Recorded by William Beynon, an ethnographer and hereditary chief of the Tsimshian Nation, the story begins with two brothers pranking each other, each trying to prove his hunting and fishing prowess over the other. When one is stranded onshore by a storm of his brother’s creation—at the site of the village that would become Klemtu—he finds himself attracted to a number of beautiful women. But the sex doesn’t go as planned, and the story ends with the transformation of a particular reproductive organ into ... a sea cucumber.

Until recently, sea cucumber fishing hasn't been much of a problem. When commercial sea cucumber harvesting began in 1971, the Kitasoo/Xai’xais had already been collecting them and monitoring their habitat for generations, with few conservation concerns. But that's changing: with the sudden influx of fishers also collecting sea cucumbers (an easy enough process if you have a boat and scuba equipment, as the creatures have no way to hide or dart away), the population rapidly decreased, stoking conservation worries.

In 1991, in response, the Canadian Department of Fisheries and Oceans (DFO) set license limits that required commercial fishers to buy licenses to participate in the harvest. Of the 85 licenses available annually, Kitasoo Seafoods holds six of them. The DFO also launched research initiatives, including the experimental fishery areas that started in 1997.

Working with the Kitasoo/Xai’xais and the industry group Pacific Sea Cucumber Harvesters Association, they set aside four stretches of coastline in different environments and divided those parcels into chunks that would be harvested at different rates. After 10 years of annual assessments, the results were used to set what were meant to be sustainable harvest rates for the commercial zones (the original quota of 514,000 pounds set in 1997 was moved up to 1.36 million pounds annually). Later, the fisheries switched from annual harvesting to a cyclical harvesting rate, where certain areas are opened up once every three years.

For Pauline Ridings, a management biologist at DFO, the study was a big success. But she points out that the research spots didn’t include areas being commercially harvested. “One of my wish lists is to actually look at the commercial fishery itself instead of having an area separate from it,” Ridings says. DFO doesn't currently do annual surveys of the commercial fishing areas, which has been expanded to 47 percent of the coastline and will likely keep growing.

That lack of surveying, combined with a too-high quota, is creating problems—at least according to the Kitasoo/Xai’xais. “Everybody here is worried they’re being overfished,” says Sandie Hankewich, who works as a biologist for Kitasoo Fisheries. “There’s concern that [a collapse] isn’t something that’s going to be noticed until it’s too far gone to recover.”

Both Hankewich and Greba share that the concern. To illustrate the danger, they point to the embattled abalone. For those unfamiliar, white abalone are considered functionally extinct along the California coast because of over-harvesting. Just like sea cucumbers, they are tasty and largely immobile, making them an easy target. Also like sea cucumbers, they’re what’s known as “broadcast spawners,” which means the males and females spew eggs and sperm into the water column to reproduce.

For both species, there must be enough adults in one area for this type of spawning to be successful. The number of white abalone grew so low that the males and females weren’t close enough to reproduce, which plunged them even closer to extinction.

Greba and Hankewich are worried the same thing might happen with sea cucumbers. “My partner Ernie has been part of the commercial fishery since it first opened up out here and he has witnessed big changes in how the densities [of sea cucumbers] used to be and how they are now,” Hankewich says. “The [crew] out fishing on the grounds right now are apparently having trouble in areas that used to be very good.”

There is some research that supports this fear. In 2014, a study in Marine Policy surveyed 20 career fishermen to find that 70 percent observed that sea cucumber abundance had declined somewhat or dramatically in recent years. But Ridings and others at DFO were skeptical of the study’s conclusion.

“We had a number of concerns with that study, one being the sample size of harvesters they spoke to,” Ridings says. She adds concerns about other aspects of the methodology, including how the participating harvesters were chosen. “[The author] provides an overall negative, one-sided view of the fishery,” Ridings says. DFO provides its own surveys for all the harvesters every year to about 100 harvesters, and usually receive eight to 14 responses each year with a mixture of positive and negative responses. “If we do receive complaints about a particular harvest area, we’ll flag it to be surveyed prior to being harvested again,” Ridings says. She adds that they know some areas of the coast tend to have fewer sea cucumbers living there, so they try not harvest those regions as heavily.

Although Hankewich is happy fishermen are being surveyed, she doesn’t think it’s a foolproof solution. There are good reasons for fishermen to be cautious about what they report on the surveys, she says. “If you talk to the guys in person, a lot will say they’ve had to fish deeper, longer, harder, with more divers in the water to get the quotas”—and that brings them close to the safety guideline limits set by the Workers’ Compensation Boards. All of which means the commercial harvesters aren’t making data collection much clearer.

Then there’s the problem of the sea cucumber itself. It’s an inscrutable animal, incredibly challenging to study despite years of effort. How do you manage a commercial fishery if you don’t understand the sea creature being fished?

“There’s a lot we don’t know about sea cucumbers because their entire body lacks hard body parts,” Hankewich says. “They’re absolutely fascinating creatures, but very challenging to learn about.”

Think about it: One of scientists’ main methods of studying the life cycle and movement of an animal is by tagging it. With sea cucumbers, there’s nothing to tag. Scientists have tried injecting tags into their bodies, but the animals just eject them. Same with dye applied to them. And as for aging—it’s practically impossible. With shellfish like clams, it’s possible to cut them open and count growth rings, like on trees. But with sea cucumbers, there’s no body part to look at that might indicate age. They have plastic bodies—meaning they can change the shape and size almost at will.

“If you touch them, they’ll contract and look almost like a little football,” Ridings says.

Then there’s their organs. Every year in the fall, sea cucumbers reabsorb all their organs and go into a sort of winter hibernation. That’s why commercial harvesters fish for them starting around October: Their skin has grown thicker and there’s little to remove internally, since they literally have no guts. In the spring, they regrow all their organs anew.

Biologists still don’t quite know how sea cucumbers survive without all their interior furniture. But they use this trick at other times, too. If they’re scared or trying to escape a predator, like a sea star, they engage in “evisceration”—ejecting all their organs and very slowly scooting away. They also have the ability to absorb food through their respiratory tree (which essentially functions as lungs), an ability that is entirely unique in the animal kingdom.

“[One thing] you need to know to properly manage a fisher is how quickly they reach a mature size, or a harvestable size after reproduction,” Hankewich says. “Another key question would be related to the Allee effect, or what density you need in a specific area for them to be able to reproduce successfully.”

DFO has done experiments with sea cucumbers in ocean pens, where the echinoderms weren’t fed and were limited to the material that grew on the wire cages for food. In those settings, the sea cucumbers required four to five years to reach harvestable size, Ridings says. But for Hankewich, those results don’t necessarily apply to wild populations.

“It doesn’t mimic exterior ocean conditions perfectly. They don’t have the currents, the same input of nutrients or other challenges, so anything you learn in a lab is kind of qualified,” he says.

The experimental fisheries project begun in 1997 was meant to provide that more nuanced information about conditions in a natural environment. But recently, all but one of the experimental areas were closed down due their proximity to salmon and shellfish farms. The problem with that proximity, according to Ridings, is the availability of edible organic material—poop—attracting sea cucumbers. They’re detritivores, which means they munch particulate matter in the sand.

“If we surveyed the experimental site that contained the fish farm and found that the numbers of sea cucumbers with that site had increased significantly, would we be able to say it was because the harvest rate was sustainable, or because the sea cucumbers were attracted to the fish farm and moved in from surrounding areas?” Ridings says. Unfortunately, she says, they wouldn’t.

The Kitasoo/Xai’xais decided to maintain their experimental area, with help from the commercial fishers. Parts of experimental area are indeed near a salmon farm—but there’s also a high current around it, which could wash most of the detritus away. Based on the input of other researchers, they think the chance of the fish farm interfering with their results is minimal, but they’re still doing extra surveys to track whether the farms are impacting the results. (Ridings says DFO would not consider any results from the ongoing experiment for setting sea cucumber quotas, but they are actively trying to develop new experiments to address these questions.)

Hankewich also points out that sea cucumbers in the wild have to deal with a number of pressures like this. “There’s other fish farms, there’s logging, there’s sea otters,” she says. “Cucumbers aren’t living in a vacuum and it just so happened that something changed on our study site and rather than dump the whole thing it makes more sense to deal with it.”

They surveyed and harvested this year for the first time in three years this fall, to reflect the cyclical model of harvesting implemented for commercial fisheries in 2011. The results haven’t been released yet, but Hankewich said they weren’t able to meet their quota for the population that was most heavily harvested, and just barely made the quota for the next area down.

“Those are vastly higher [percentages] than what’s fished at the commercial fishery,” Hankewich says. “But it does show that certain levels are going to be unsustainable.” And what if the lower levels of harvesting are also unsustainable, but it just takes longer to become apparent? By keeping their experimental area open, that’s what Hankewich and the Kitasoo/Xai’xais hope to find out.

.....

Ultimately, DFO and the Kitasoo/Xai’xais want the same thing: for sea cucumber populations in Canada to be sustainable in the long term. But they have different ideas of how to get there, and different views on how the sea cucumbers are doing right now.

“The Kitasoo have developed a cucumber harvest plan where we’ve got refugia set aside and no-take zones set aside,” Hankewich says. “It’s sort of an insurance policy.” But DFO and industry fishers haven’t bought into the plan yet. Both groups think the amount of coastline set aside as refugia, or protected areas, should be much smaller.

Ridings says the stocks are at a healthy level; she sees no reason to be concerned about harvesting, though DFO is keeping an eye on other things that might be problems in the more distant future, like climate-change related problems.

Greba and Hankewich are slightly less confident. “I wish I could be optimistic, but I have some concerns. There are certain areas where the fishery does not seem to have been sustainable and certain areas have been fished hard in the past and don’t seem to be recovering,” Hankewich says. “We need to be able to change our management to reflect that, and give the cucumbers a break.”

But in the meantime, they’ll keep harvesting on a local level. Sea cucumbers will keep appearing in regular meals in Klemtu, and being sent across an ocean to hungry consumers in China, and stymying every effort by scientists to unravel their slimy secrets.

Reporting for this story made possible in part by the Institute for Journalism and Natural Resources.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/lorraine.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/lorraine.png)