The Myth of Fingerprints

Police today increasingly embrace DNA tests as the ultimate crime-fighting tool. They once felt the same way about fingerprinting

:focal(331x262:332x263)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/e0/e6/e0e6fd99-031b-4a3e-b016-22637c12ac5a/extended_fingerprints_art-updated.jpg)

At 9:00 a.m. last December 14, a man in Orange County, California, discovered he’d been robbed. Someone had swiped his Volkswagen Golf, his MacBook Air and some headphones. The police arrived and did something that is increasingly a part of everyday crime fighting: They swabbed the crime scene for DNA.

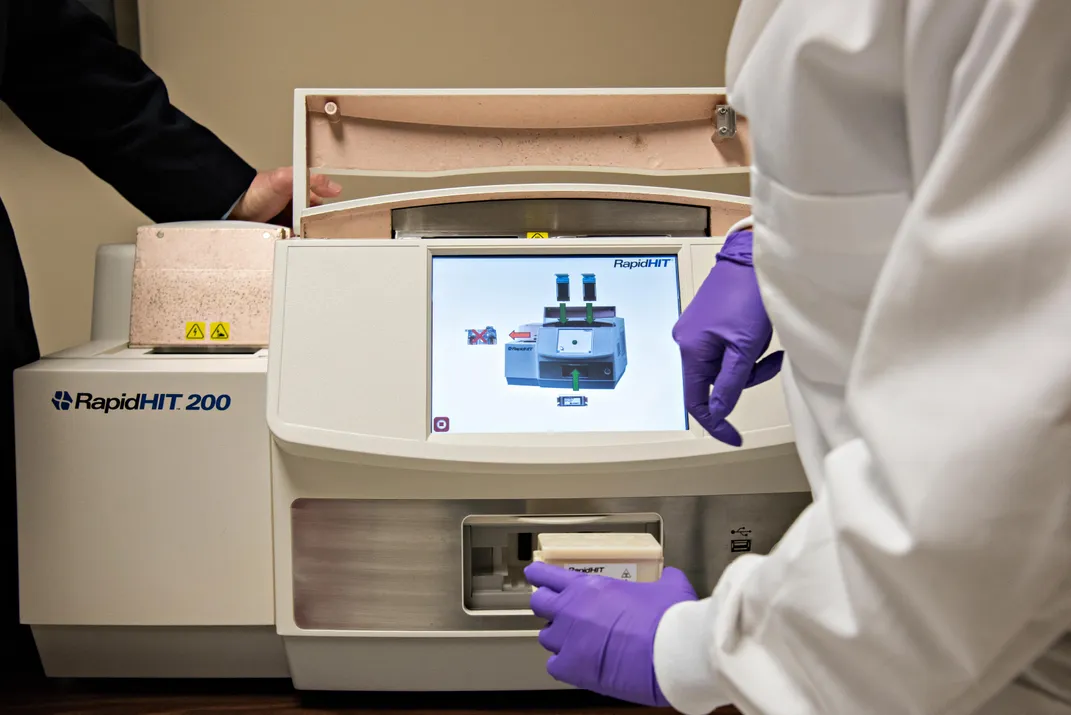

Normally, you might think of DNA as the province solely of high-profile crimes—like murder investigations, where a single hair or drop of blood cracks a devilish case. Nope: These days, even local cops are wielding it to solve ho-hum burglaries. The police sent the swabs to the county crime lab and ran them through a beige, photocopier-size “rapid DNA” machine, a relatively inexpensive piece of equipment affordable even by smaller police forces. Within minutes, it produced a match to a local man who’d been previously convicted of identity theft and burglary. They had their suspect.

DNA identification has gone mainstream—from the elite labs of “CSI” to your living room. When it first appeared over 30 years ago, it was an arcane technique. Now it’s woven into the fabric of everyday life: California sheriffs used it to identify the victims of their recent wildfires, and genetic testing firms offer to identify your roots if you mail them a sample.

Yet the DNA revolution has unsettling implications for privacy. After all, you can leave DNA on everything you touch—which means, sure, crimes can be more easily busted, but the government can also more easily track you. And while it’s fun to learn about your genealogy, your cheek samples can wind up in places you’d never imagine. FamilyTreeDNA, a personal genetic service, in January admitted it was sharing DNA data with federal investigators to help them solve crimes. Meanwhile consumer DNA testing firm 23andMe announced that it was now sharing samples sent to them with the pharmaceutical giant GlaxoSmithKline to make “novel treatments and cures.”

What happens to a society when there’s suddenly a new way to identify people—to track them as they move around the world? That’s a question that the denizens of the Victorian turn of the century pondered, as they learned of a new technology to hunt criminals: fingerprinting.

* * *

For centuries, scholars had remarked on the curious loops and “whorls” that decorated their fingertips. In 1788, the scientist J.C.A. Mayers declared that patterns seemed unique—that “the arrangement of skin ridges is never duplicated in two persons.”

It was an interesting observation, but one that lay dormant until 19th-century society began to grapple with an emerging problem: How do you prove people are who they say they are?

Carrying government-issued identification was not yet routine, as Colin Beavan, author of Fingerprints, writes. Cities like London were booming, becoming crammed full of strangers—and packed full of crime. The sheer sprawl of the population hindered the ability of police to do their work because unless they recognized criminals by sight, they had few reliable ways of verifying identities. A first-time offender would get a light punishment; a habitual criminal would get a much stiffer jail sentence. But how could the police verify whether a perpetrator they hauled in had ever been caught previously? When recidivists got apprehended, they’d just give out a fake name and claim it was their first crime.

“A lot of that is the function of the increasing anonymity of modern life,” notes Charles Rzepka, a Boston University professor who studies crime fiction. “There’s this problem of what Edgar Allan Poe called ‘The Man of the Crowd.’” It even allowed for devious cons. One man in Europe claimed to be “Roger Tichborne,” a long-lost heir to a family baronetcy, and police had no way to prove he was or wasn’t.

Faced with this problem, police tried various strategies for identification. Photographic mug shots helped, but they were painstakingly slow to search through. In the 1880s, a French police official named Alphonse Bertillon created a system for recording 11 body measurements of a suspect, but it was difficult to do so accurately.

The idea of fingerprints gradually dawned on several different thinkers. One was Henry Faulds, a Scottish physician who was working as a missionary in Japan in the 1870s. One day while sifting through shards of 2,000-year-old pottery, he noticed that the ridge patterns of the potter’s ancient fingerprints were still visible. He began inking prints of his colleagues at the hospital—and noticing they seemed unique. Faulds even used prints to solve a small crime. An employee was stealing alcohol from the hospital and drinking it in a beaker. Faulds located a print left on the glass, matched it to a print he’d taken from a colleague, and—presto—identified the culprit.

How reliable were prints, though? Could a person’s fingerprints change? To find out, Faulds and some students scraped off their fingertip ridges, and discovered they grew back in precisely the same pattern. When he examined children’s development over two years, Faulds found their prints stayed the same. By 1880 he was convinced, and wrote a letter to the journal Nature arguing that prints could be a way for police to deduce identity.

“When bloody finger-marks or impressions on clay, glass, etc., exist,” Faulds wrote, “they may lead to the scientific identification of criminals.”

Other thinkers were endorsing and exploring the idea—and began trying to create a way to categorize prints. Sure, fingerprints were great in theory, but they were truly useful only if you could quickly match them to a suspect.

The breakthrough in matching prints came from Bengal, India. Azizul Haque, the head of identification for the local police department, developed an elegant system that categorized prints into subgroups based on their pattern types such as loops and whorls. It worked so well that a police officer could find a match in only five minutes—much faster than the hour it would take to identify someone using the Bertillon body-measuring system. Soon, Haque and his superior Edward Henry were using prints to identify repeat criminals in Bengal “hand over fist,” as Beavan writes. When Henry demonstrated the system to the British government, officials were so impressed they made him assistant commissioner of Scotland Yard in 1901.

Fingerprinting was now a core tool in crime-busting. Mere months after Henry set up shop, London officers used it to fingerprint a man they’d arrested for pickpocketing. The suspect claimed it was his first offense. But when the police checked his prints, they discovered he was Benjamin Brown, a career criminal from Birmingham, who’d been convicted ten times and printed while in custody. When they confronted him with their analysis, he admitted his true identity. “Bless the finger-prints,” Brown said, as Beavan writes. “I knew they’d do me in!”

* * *

Within a few years, prints spread around the world. Fingerprinting promised to inject hard-nosed objectivity into the fuzzy world of policing. Prosecutors historically relied on witness testimony to place a criminal in a location. And testimony is subjective; the jury might not find the witness credible. But fingerprints were an inviolable, immutable truth, as prosecutors and professional “fingerprint examiners” began to proclaim.

“The fingerprint expert has only facts to consider; he reports simply what he finds. The lines of identification are either there or they are absent,” as one print examiner argued in 1919.

This sort of talk appealed to the spirit of the age—one where government authorities were keen to pitch themselves as rigorous and science-based.

“It’s this turn toward thinking that we have to collect detailed data from the natural world—that these tiniest details could be more telling than the big picture,” says Jennifer Mnookin, dean of the UCLA law school and an expert in evidence law. Early 20th-century authorities increasingly believed they could solve complex social problems with pure reason and precision. “It was tied in with these ideas of science and progressivism in government, and having archives and state systems of tracking people,” says Simon Cole, a professor of criminology, law, and society at the University of California, Irvine, and the author of Suspect Identities, a history of fingerprinting.

Prosecutors wrung high drama out of this curious new technique. When Thomas Jennings in 1910 was the first U.S. defendant to face a murder trial that relied on fingerprinted evidence, prosecutors handed out blown-up copies of the prints to the jury. In other trials, they would stage live courtroom demonstrations of print-lifting and print-matching. It was, in essence, the birth of the showily forensic policing that we now see so often on “CSI”-style TV shows: perps brought low by implacably scientific scrutiny. Indeed, criminals themselves were so intimidated by the prospect of being fingerprinted that, in 1907, a suspect arrested by Scotland Yard desperately tried to slice off his own prints while in the paddy wagon.

Yet it also became clear, over time, that fingerprinting wasn’t as rock solid as boosters would suggest. Police experts would often proclaim in court that “no two people have identical prints”—even though this had never been proven, or even carefully studied. (It’s still not proven.)

Although that idea was plausible, “people just asserted it,” Mnookin notes; they were eager to claim the infallibility of science. Yet quite apart from these scientific claims, police fingerprinting was also simply prone to error and sloppy work.

The real problem, Cole notes, is that fingerprinting experts have never agreed on “a way of measuring the rarity of an arrangement of friction ridge features in the human population.” How many points of similarity should two prints have before the expert analyst declares they’re the same? Eight? Ten? Twenty? Depending on what city you were tried in, the standards could vary dramatically. And to make matters more complex, when police lift prints from a crime scene, they are often incomplete and unclear, giving authorities scant material to make a match.

So even as fingerprints were viewed as unmistakable, plenty of people were mistakenly sent to jail. Simon Cole notes that at least 23 people in the United States have been wrongly connected to crime-scene prints.* In North Carolina in 1985, Bruce Basden was arrested for murder and spent 13 months in jail before the print analyst realized he’d made a blunder.

Nonetheless, the reliability of fingerprinting today is rarely questioned in modern courts. One exception was J. Spencer Letts, a federal judge in California who in 1991 became suspicious of fingerprint analysts who’d testified in a bank robbery trial. Letts was astounded to hear that the standard for declaring that two prints matched varied widely from county to county. Letts threw out the fingerprint evidence from that trial.

“I don’t think I’m ever going to use fingerprint testimony again,” he said in court, sounding astonished, as Cole writes. “I’ve had my faith shaken.” But for other judges, the faith still holds.

* * *

The world of DNA identification, in comparison, has received a slightly higher level of skepticism. When it was first discovered in 1984, it seemed like a blast of sci-fi precision. Alec Jeffreys, a researcher at the University of Leicester in England, had developed a way to analyze pieces of DNA and produce an image that, Jeffreys said, had a high likelihood of being unique. In a splashy demonstration of his concept, he found that the semen on two murder victims wasn’t from the suspect police had in custody.

DNA quickly gained a reputation for helping free the wrongly accused: Indeed, the nonprofit Innocence Project has used it to free over 360 prisoners by casting doubt on their convictions. By 2005, Science magazine said DNA analysis was the “gold standard” for forensic evidence.

Yet DNA identification, like fingerprinting, can be prone to error when used sloppily in the field. One problem, notes Erin Murphy, professor of criminal law at New York University School of Law, is “mixtures”: If police scoop up genetic material from a crime scene, they’re almost certain to collect not just the DNA of the offender, but stray bits from other people. Sorting relevant from random is a particular challenge for the simple DNA identification tools increasingly wielded by local police. The rapid-typing machines weren’t really designed to cope with the complexity of samples collected in the field, Murphy says—even though that’s precisely how some police are using them.

“There’s going to be one of these in every precinct and maybe in every squad car,” Murphy says, with concern. When investigating a crime scene, local police may not have the training to avoid contaminating their samples. Yet they’re also building up massive databases of local citizens: Some police forces now routinely request a DNA sample from everyone they stop, so they can rule them in or out of future crime investigations.

The courts have already recognized the dangers of badly managed DNA identification. In 1989—only five years after Jeffreys invented the technique—U.S. lawyers successfully contested DNA identification in court, arguing that the lab processing the evidence had irreparably contaminated it. Even the prosecution agreed it had been done poorly. Interestingly, as Mnookin notes, DNA evidence received pushback “much more quickly than fingerprints ever did.”

It even seems the public has grasped the dangers of its being abused and misused. Last November, a jury in Queens, New York, deadlocked in a murder trial—after several of them reportedly began to suspect the accused’s DNA had found its way onto the victim’s body through police contamination. “There is a sophistication now among a lot of jurors that we haven’t seen before,” Lauren-Brooke Eisen, a senior fellow at the Brennan Center for Justice, told the New York Times.

To keep DNA from being abused, we’ll have to behave like good detectives—asking the hard questions, and demanding evidence.

*Editor's Note, April 26, 2019: An earlier version of this story incorrectly noted that at least 23 people in the United States had been imprisoned after being wrongly connected to crime-scene prints. In fact, not all 23 were convicted or imprisoned. This story has been edited to correct that fact. Smithsonian regrets the error.

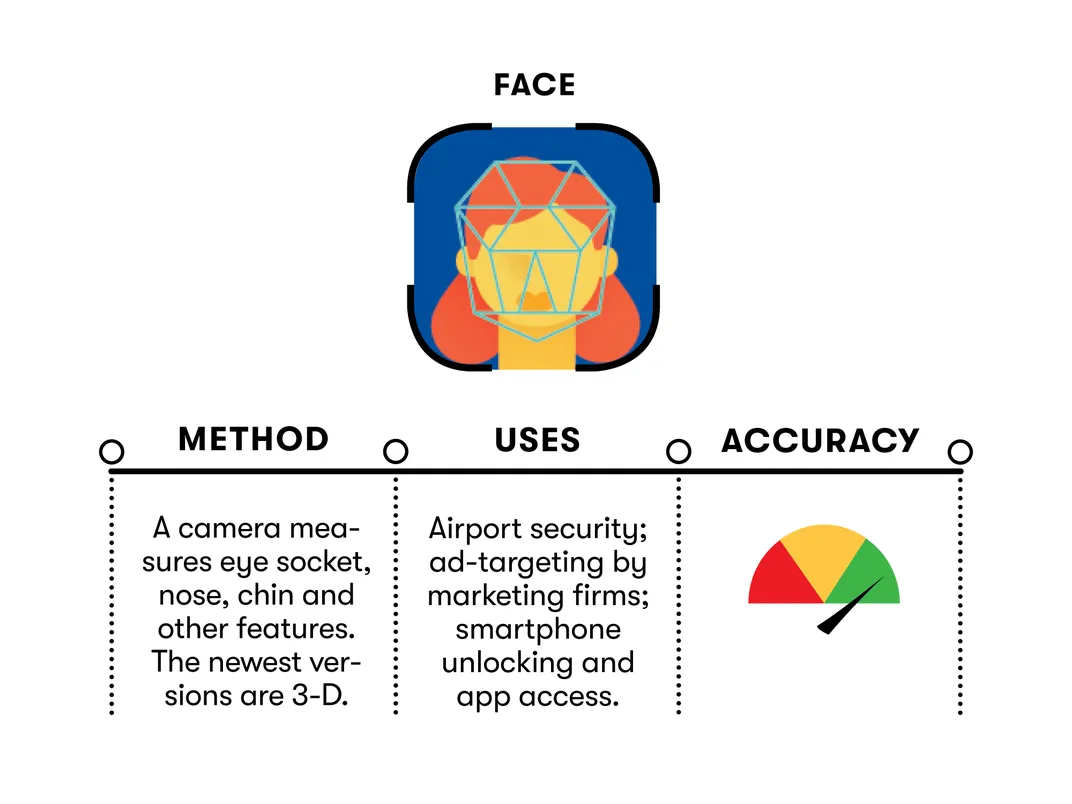

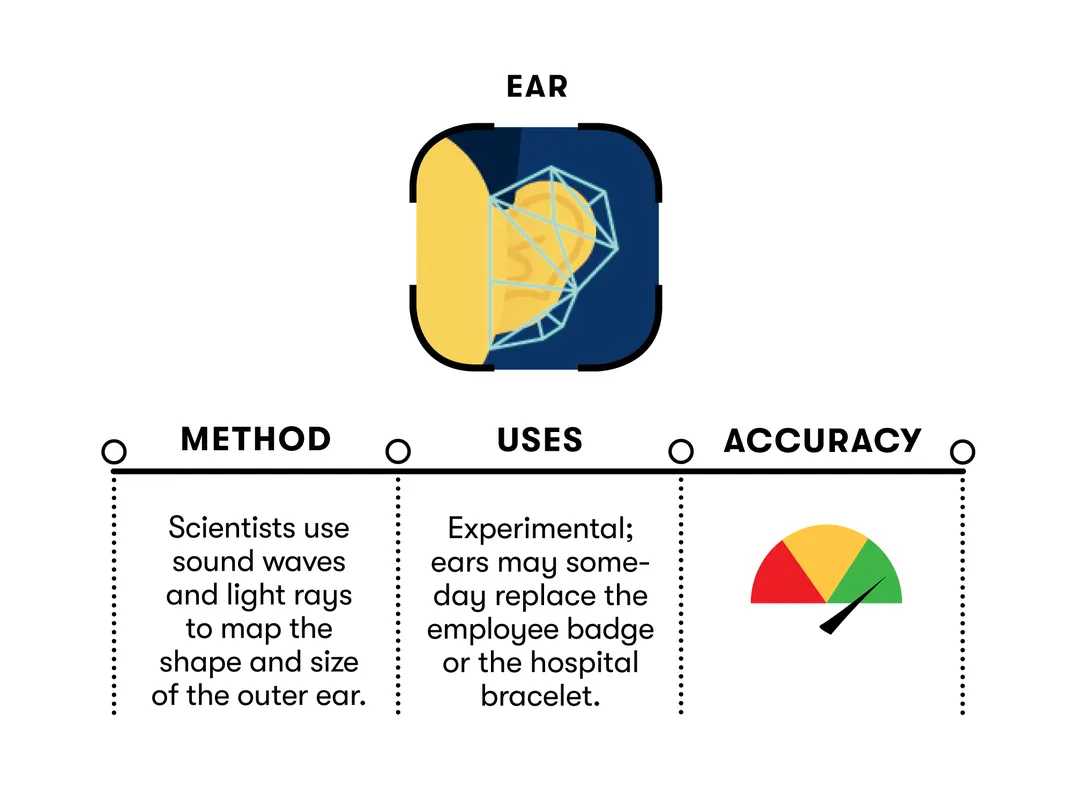

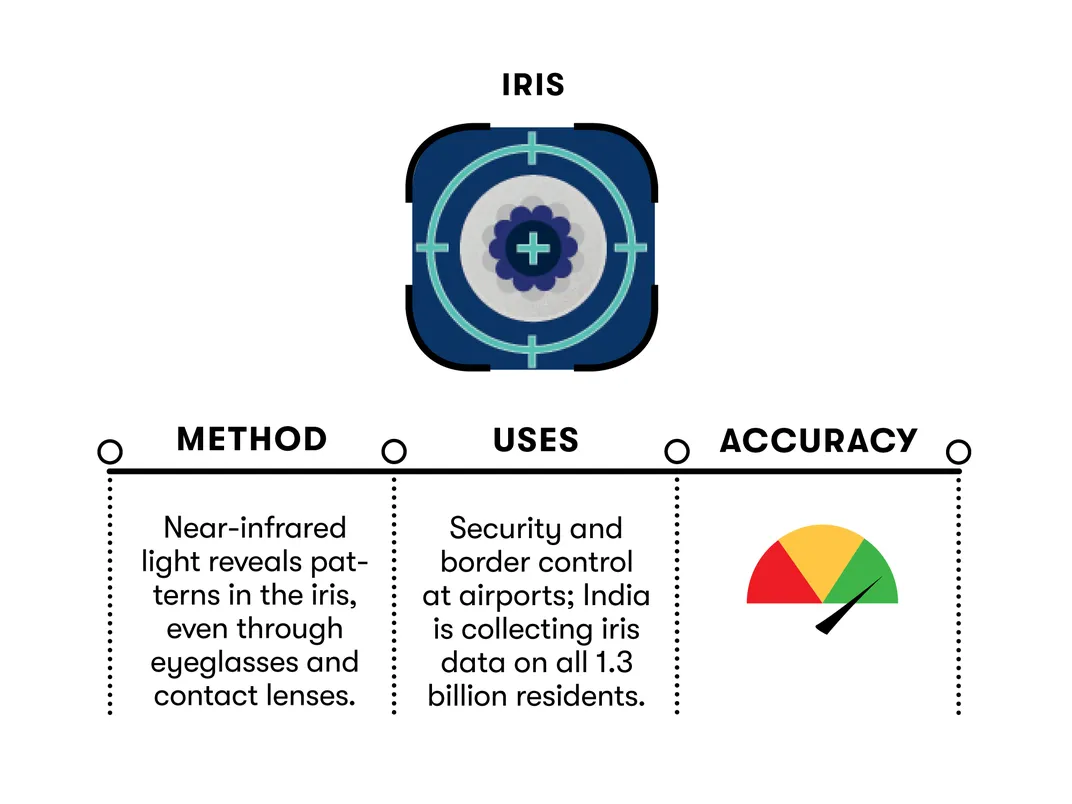

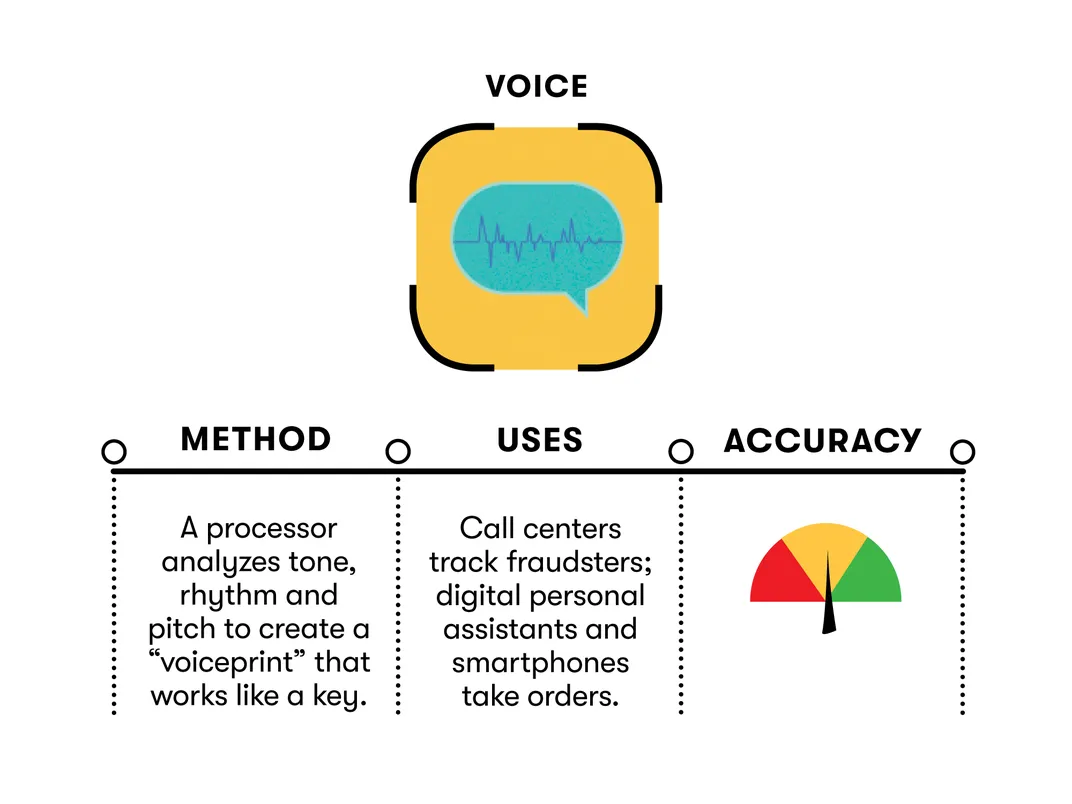

Body of Evidence

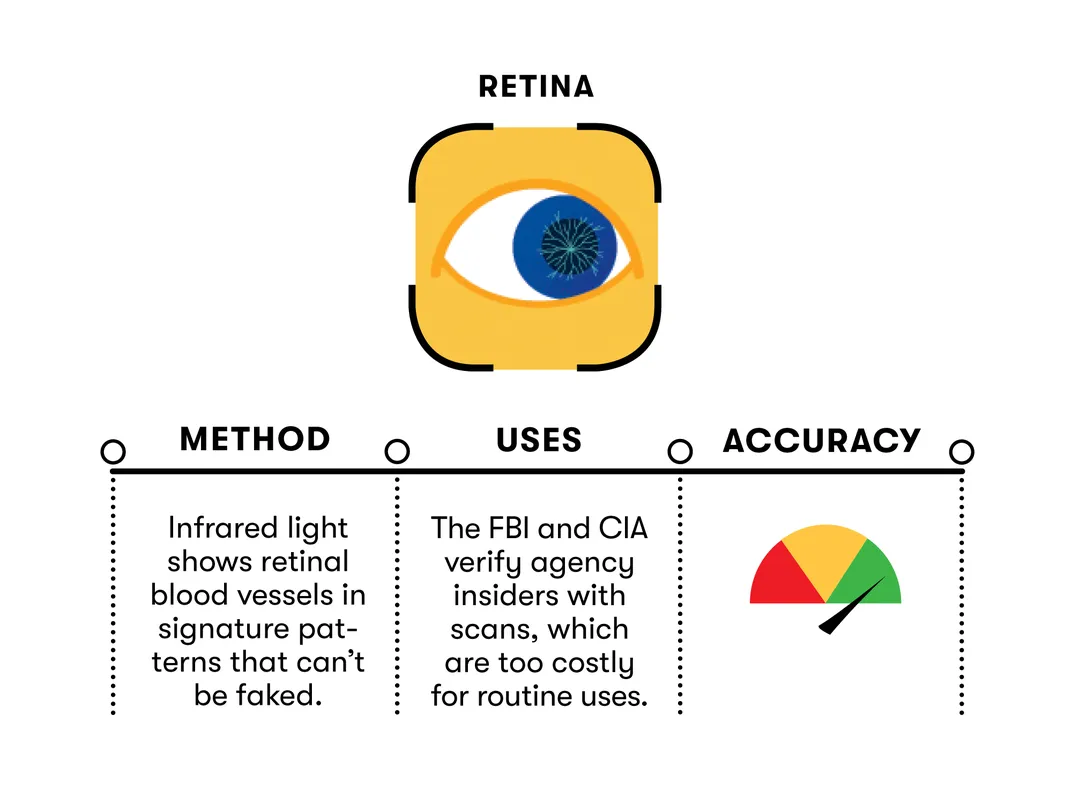

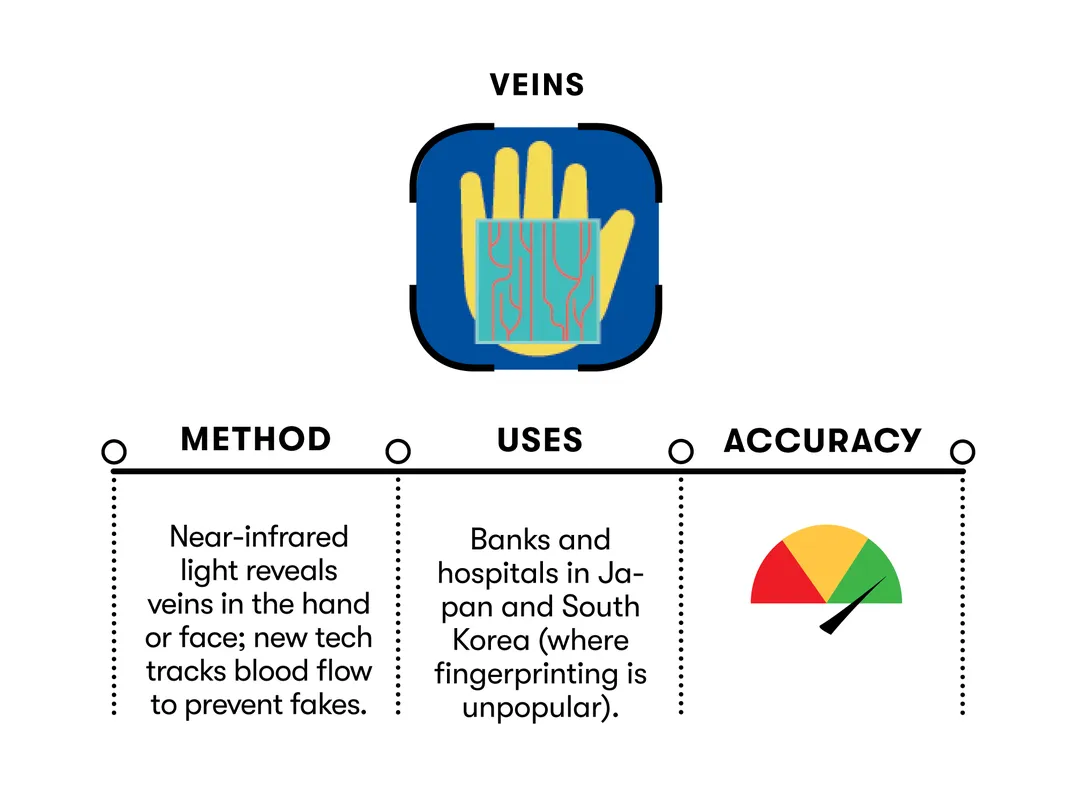

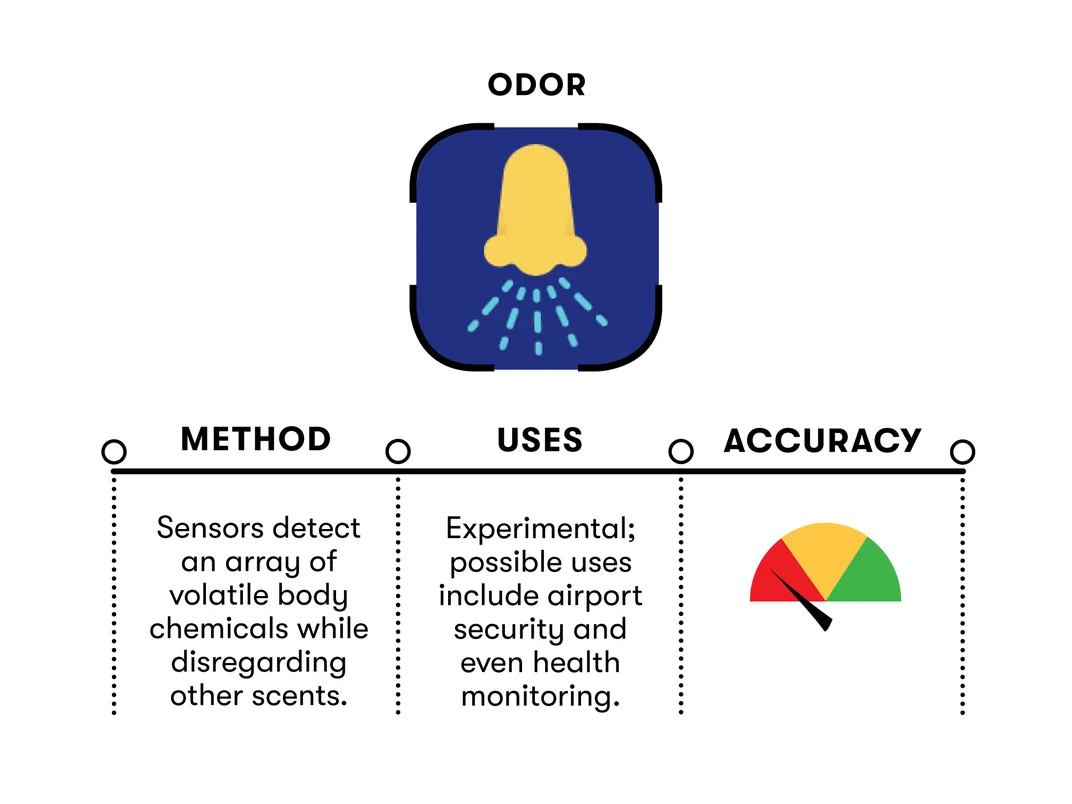

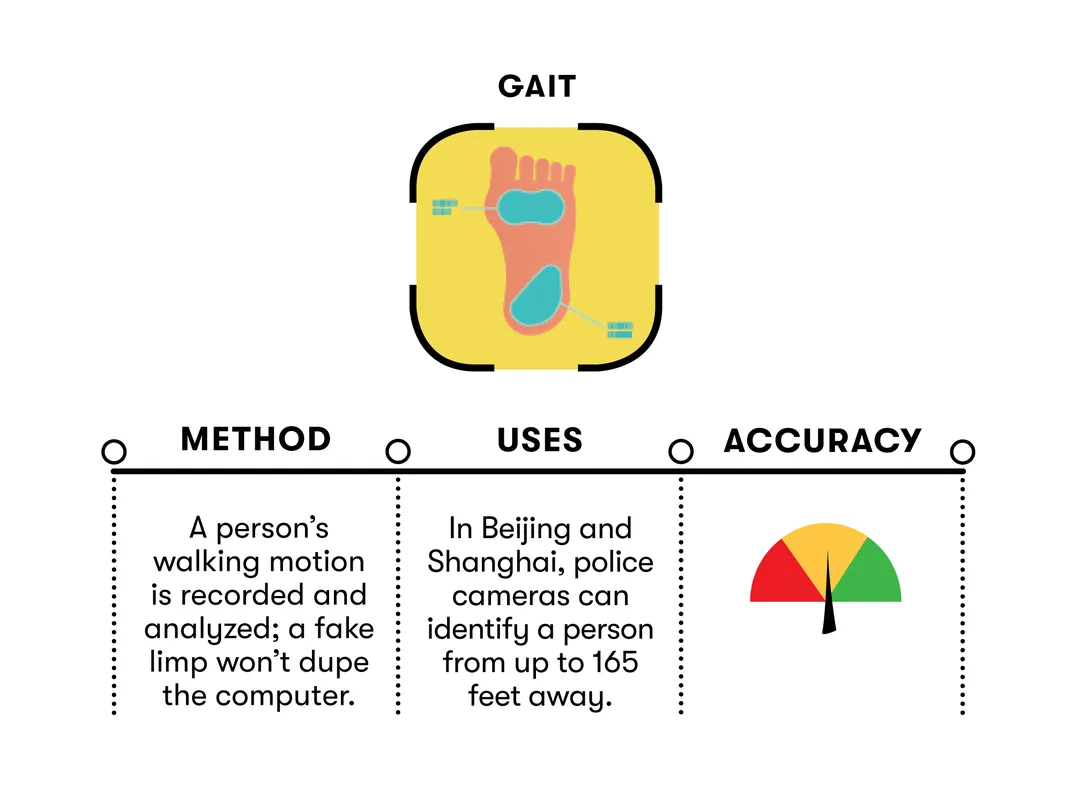

Now science can identify you by your ears, your walk and even your scent

Research by Sonya Maynard

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Clive_Thompson_photo_credit_is_Tom_Igoe.jpg)