NASA Considers a Rover Mission to Go Cave Diving on the Moon

The deep caverns and pits that dot the lunar surface could hold clues to the moon’s history and perhaps provide shelter for future human exploration

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/2e/f5/2ef571fd-d48d-43be-a6b3-5944985468bf/earthshine_bigger2.jpg)

Half a century after Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin took their first steps across the moon’s Mare Tranquillitatis, or the Sea of Tranquility, scientists want to send a robotic explorer to the same lunar region for a deeper dive. An extreme-terrain rover concept called Moon Diver, to launch in the mid-2020s if approved by NASA, would descend into one of the enormous pits dotting the surface of the moon. The walls of the cave under consideration for the spelunking spacecraft are about 130 feet deep, followed by another 200 feet of freefall into a deep, dark, mysterious maw beneath the lunar surface.

“There is a nice poetry to this mission concept,” says Laura Kerber, a research scientist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory and the Moon Diver mission concept principal investigator. “Apollo 11 landed along the edge of the Sea of Tranquility. Fifty years later, we are going to dive down right into the middle of it.”

Scientists at the 50th Lunar and Planetary Science Conference (LPSC) in Texas on March 20 presented plans for Moon Diver, designed to rappel hundreds of feet down into large pits on the moon’s surface. During descent, science instruments in the rover’s wheel wells would unfold and study the ancient moon by way of its exposed stratigraphy—the layers of rock hidden below the surface.

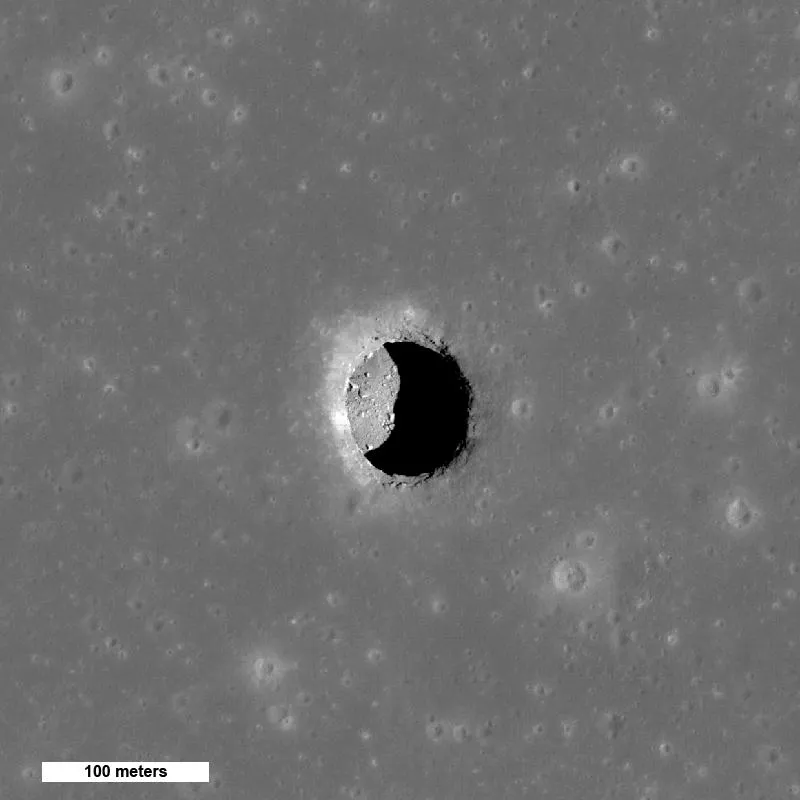

There are over a dozen deep pits known on the moon, all located in its mare—the lava-covered parts of the lunar surface that have cooled into dark, basaltic plains. Some of these pits are as wide as a football field and big enough to swallow entire buildings. They formed as voids in the lunar subsurface whose ceilings eventually collapsed, creating cavernous openings. These cavities expose fresh cuts of rock that are of particular interest to planetary geologists—slices of the moon’s rock record that have been largely unaltered for billions of years.

A spelunking Moon Diver rover could reveal the types, fluxes and timescales of ancient lava eruptions on the moon. The rover could discover what sort of lava flowed, how much erupted, its speed and intensity. By studying lunar lava, planetary scientists can work out whether the volcanic activity was robust enough to give the moon a Mars-like atmosphere in the distant past. More information about the moon’s eruptions could also help elucidate the catastrophic effects volcanoes have had on the climate of Mars.

Scientists are also interested in lunar caverns because they could provide shelter for future equipment or even crewed research centers. Below the moon’s surface, astronauts would be shielded from radiation, micrometeorites, the harmful effects of lunar dust and the dramatic temperature swings between lunar night and day. But before anyone could start building a subterranean moon base, scientists need to get a better sense of what lurks below the lunar maria.

Moon Diver would touch down within a few hundred feet of its target pit and act as an anchor for a simple two-wheeled rover called Axel. Unlike any other rover landed on another world, Axel would not require a ramp to roll off of its lander element; it was designed to rappel down things. A tether to the rover would provide it with power and communications as it descends.

Axel would carry multiple instrument payloads to survey a lunar cavern, including a stereo pair of cameras for close imaging of the walls and a long-distance camera to look across at the opposite side of the pit. A multispectral microscope would detail the mineralogy of the cavern, while an alpha particle x-ray spectrometer would study the elemental chemistry of the rock features.

The outer geometry of the target pit in the Sea of Tranquility is shaped like a funnel, and the rover would roll down the staircase-like walls. As terrain grows increasingly rough, Axel could operate the way a human rappeler might descend: swinging and tapping against the walls. Where it touches, the science instruments could deploy and collect data, and during the wall-less, 200-foot rappel, the rover could take images of its surroundings while dangling helplessly as it is lowered with the tether.

Once it reaches the bottom of the pit, Kerber says, Axel would explore the cavern floor, providing humanity’s first close look at the subterranean realms of the moon. The rover would carry six times as much tether as it needs, so however far the bottom of the cavern is, Axel should be able to descend deeply enough to discover what waits below.

“The bottom of the pit is total exploration. We have enough time to just see what the heck is down there. We are thinking a monolith,” Kerber jokes, “or a big door covered in hieroglyphics.”

Moon Diver will be competing for selection as part of NASA’s low-cost, Discovery-class mission program. If chosen, the mission would launch for the moon around 2025. Competing proposals presented at LPSC include a mission to Triton, the largest moon of Neptune, and one to Io, the volcanic satellite of Jupiter.

As part of its long-term goal of lunar exploration, NASA plans to construct a lunar outpost in orbit around the moon and to use the station as stepping stone for crewed missions to the surface. But before astronauts return, a little two-wheeled rover could scout out the deep lunar pits to see if humanity’s future on the moon resides in the caverns below.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/DavidBrown.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/DavidBrown.png)