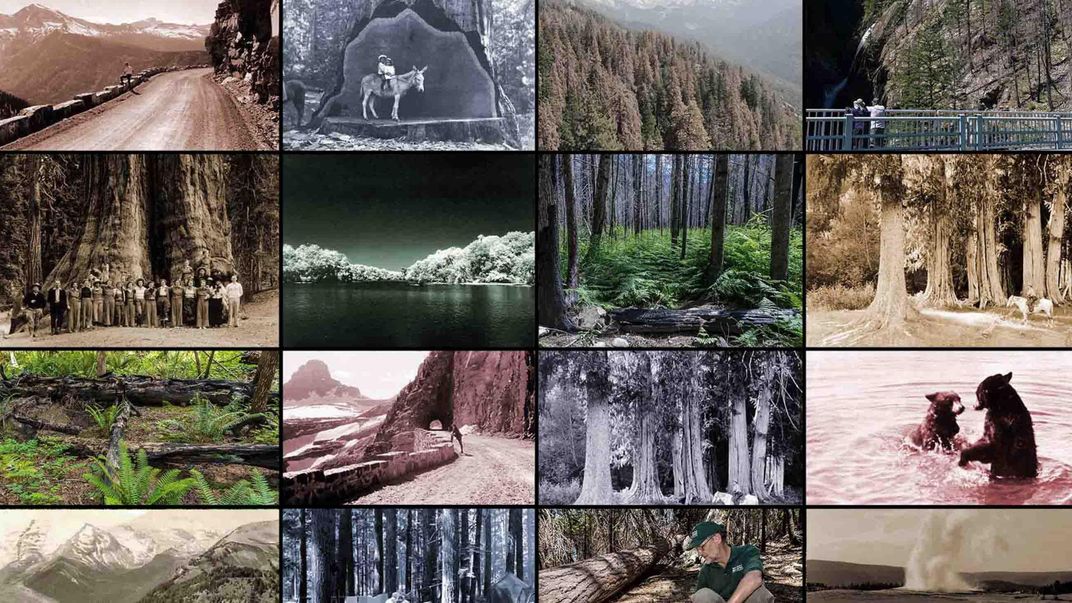

The National Parks Face a Looming Existential Crisis

Political uncertainty and a changing climate converge to forge the park system’s biggest challenge yet

:focal(2720x1360:2721x1361)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/fc/f2/fcf24b24-e1ec-4edf-98b5-1a2307bfee64/f0w009.jpg)

This article originally appeared on Undark. For more articles like this, please visit undark.org.

When I drove with forest ecologist Nathan Stephenson on the twisted Generals Highway through Sequoia National Park in central California last September, it was like a tour through the aftermath of a disaster. As we zigzagged up the road in his car, Stephenson narrated our journey blithely, like a medical examiner used to talking about death. “There’s a dead skeleton there,” he remarked, pointing to a bony oak corpse jutting toward the sky. A haze of nude branches clung to the distant slope.

“So all that gray up there is dead live oaks,” he said.

Above us, a band of brown streaked across the slopes—dead pines, their remains still standing upright in the forest—and when we reached nearly 6,000 feet, Stephenson parked on a gated road and led me into a desolate scene of parched earth and dying trees.

Tall and lanky as a sapling, with angular shoulders and a neatly trimmed white beard, Stephenson—who, at 60 years old, has worked here since he began as a National Park Service volunteer nearly four decades ago—looked like he could have sprung from the forest himself. Today, as a full-time research scientist with the United States Geological Survey, stationed in the Sierra Nevada, one of Stephenson’s main jobs is to keep watch over these trees. He tromped through a carpet of brown needles and paper-dry oak leaves to show me a deceased Ponderosa pine about six feet wide at the base and as tall as a 15-story building. Someone from his research crew had peeled the bark back to reveal the cause of death: the curled signature of a pine beetle etched into the wood.

“And there’s another Ponderosa pine,” he said, pointing a few feet away. “They all died.”

Drought suppresses a tree’s ability to make sap, which functions as part of both its circulatory system and its immune system against bugs. About a decade ago, even before the historic California drought, Stephenson and his colleagues saw a slight but noticeable uptick in the number of insect-inflicted casualties in the forest—twice as many as when he started his research—and he suspected that the rising temperatures were stressing the trees.

The mass death of trees, pines especially, accelerated after the winter of 2014-2015 when the weather went haywire and Stephenson walked the foothills in a short-sleeved T-shirt in January, and again during the record-low snowfalls the following year. Then came the swarms of beetles, which appear to be thriving amid the warmer temperatures. That spring, “it was like, ‘Oh my gosh, everything’s dropping dead,’” Stephenson recalled.

Since then, about half to two-thirds of the thick-trunked pines at this elevation have been lost, along with an increased number of fatalities among other species like incense cedars (trees that seemed so hardy before the drought that Stephenson and his colleagues used to call them “the immortals”). His crew keeps a running count of the casualties, but the park doesn’t intervene to save the trees.

Even though the National Park Service is charged with keeping places like Sequoia “unimpaired” for future generations, it doesn’t usually step in when trees meet their end because of thirst and pestilence. Droughts and insects are supposed to be normal, natural occurrences. But it’s hard to say whether the changes witnessed here—or at neighboring Kings Canyon National Park, or at national parks across the nation—still count as normal, or even “natural,” at least as park stewards like Stephenson have long understood the term. And those changes raise a lot of prickly questions that cut to the very heart of what keepers of public lands do, and how they perceive their mission.

After all, even as tens of millions of tourists throng through their gates every year to get a glimpse of the “wild,” official policy has, for decades, directed scientists and managers to keep the parks they oversee as untainted as possible, looking as nature would if humans had never intervened. But how do you preserve the wilderness when nature itself is no longer behaving like it’s supposed to? How do you erase human influence when that influence is now everywhere, driving up temperatures, acidifying oceans, melting glaciers, and rapidly remaking the landscapes we’ve come to know as our national parks?

In Alaska, boreal forest trees are rooting into the previously treeless tundra. The javelina, a hoofed, pig-like mammal, has wandered north from part of its traditional range in southern Arizona into Grand Canyon National Park. The glaciers of Glacier National Park are withering in the heat and will probably be gone in less than 15 years.

Under the Obama administration, the park service took on climate change as a kind of combat mission. A quote from then-National Park Service director Jonathan Jarvis is still emblazoned across a number of agency websites: “I believe climate change is fundamentally the greatest threat to the integrity of our national parks that we have ever experienced.” Three years ago, a memo sent to directors and managers of every region of the park service confessed that “some goals described in our current planning documents reflect concepts of ‘naturalness’ that are increasingly difficult to define in a world shaped by an altered climate.”

Those realizations were already upending the park service and its affiliated agencies when the nation elected its new president, Donald Trump, who has famously called climate change a “hoax.” Since arriving in Washington, the administration has been busy erasing references to climate science on federal websites, and in June, Trump officially withdrew from the Paris climate accord, a landmark global pact reached just two years ago. Several of Trump’s cabinet members and nominees have hedged on their views regarding climate science—including former congressman Ryan Zinke, whom Trump has put in charge of the U.S. Department of the Interior, which oversees the park service.

Meanwhile, the agency’s 22,000 olive-and-gray-clad rangers, scientists, and other staff have recently acquired a near-mythical reputation as a cadre of outlaws fighting to avenge assaults on climate science. The internet and social media buzzed with enthusiasm when Badlands National Park’s Twitter account “went rogue” and posted a series of facts about global carbon dioxide concentrations, and spoof national park Twitter accounts proliferated under names like @BadHombreNPS and @AltNatParkSer.

But it’s really nature itself that is going rogue, and while the current administration may dismiss climate change, managers and scientists in places like Sequoia National Park can already see its impacts first-hand. Figuring out what to do about it—or even whether they should do something about it—has been as much an existential journey as a scientific one for the overseers of the nation’s parks. With the evidence all around them, they have spent the last several years painstakingly tracking fire and drought, gathering data from trees and soils, and developing models of possible futures—including ones that might usher in leaders who are unsympathetic to their cause.

“It’s our responsibility under the law to understand and respond to threats to the people’s resources,” said Gregor Schuurman, an ecologist with the National Park Service’s Climate Change Response Program. “Those of us engaged in that try as much as possible to not be too influenced by the day-to-day politics, which are often pretty volatile.” Nonetheless, Schuurman admitted, the threats to parks from climate change are “ongoing” and “concerning.”

For all of this, Stephenson remains optimistic. “Most trees are alive,” he told me. “I’m so used to this idea that we’re going to be seeing big changes that it’s sort of like, ‘Okay, here’s step one. This is our learning opportunity.’”

When the National Park Service was formed in 1916 to take care of the “scenery and the natural and historic objects and the wild life” in the parks, it didn’t initially treat nature with that much reverence. It was more focused on providing attractions to visitors. Park managers cut a tunnel in a giant sequoia tree in Yosemite so you could drive your car through it, encouraged visitors at Western parks to watch the bears feeding nightly from the garbage dumps, and in the agency’s first decade, frequently gunned down wolves, cougars and other predators they considered a nuisance.

All of this changed in 1962, when A. Starker Leopold, the son of renowned conservationist Aldo Leopold, was put in charge of a committee to examine how to manage wildlife in the parks and whether to allow hunting. He and his committee gave the park service more than it asked for: a sweeping statement of principles that set the parks on what might now look like a quixotic mission. “A national park should represent a vignette of primitive America,” their report declared—something resembling the landscape before European settlers started tampering with it.

The report largely omitted the myriad ways that indigenous people had, of course, managed ecosystems for many thousands of years. But in many ways, it transformed the park service from a tourism bureau into one of the country’s leading agencies for ecosystem science. It advised parks to abide by the best principles of ecology and to keep intact the many interdependent relationships among different species (like the ways that wolves keep deer populations in check so they don’t destroy too much vegetation). After the Leopold Report, parks put an end to most practices, such as bear-feeding, that treated wild animals like entertainment.

Early in Stephenson’s career, he internalized the Leopold tradition and saw it as his mission to help make the forests look something like they did when conservationist John Muir tromped through them in the 1860s and 1870s—sun-speckled groves of thick-trunked sequoias, pines, cedars and firs. In 1979, he spent his first season as a volunteer, hiking through the backcountry to catalog the park’s remote campsites. Then he worked for a few years as a low-paid seasonal employee—until he helped launch a climate change research project in the park in the 1990s. “I wanted to be here so badly,” he recalled.

Over the years, part of his work with his forestry colleagues has involved providing information to help correct Sequoia National Park’s fire problem.

Many Western landscapes, including Muir’s beloved sequoia groves, are adapted to wildfires. But before the Leopold Report, firefighters had feverishly extinguished even small fires in the Sierras, and the results were sometimes disastrous. The sequoias, which need light and fire to germinate, languished in thick shade and stopped producing seedlings. In the absence of little fires, forests became dense and stockpiled with flammable bits of tree and leaf debris, and the risk of bigger, hotter, unstoppable infernos grew. In the late 1960s, Sequoia National Park began to fix the problem by lighting low, tame ground fires in the park—“prescribed burning,” as it’s known—a practice that has persisted in part because it works, but also because it is supposed to imitate a natural process, as Leopold instructed.

By the mid-1990s, though, it became clear to Stephenson that recreating the forests of centuries past this way was an unreachable goal. Two of his colleagues used scars on old trees to calculate how many fires burned through the forests of Sequoia before Europeans got there; it was far more than the number of blazes the park’s burn crew had deliberately set on their own. Stephenson realized that, given the vastness of the park and the small number of scientists and firefighters on staff, it would be nearly impossible to recreate the forests that once were. Meanwhile, Stephenson read early predictions of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, the international body that distills the best climate science from around the world. Already the IPCC was painting a dire picture: “many important aspects of climate change are effectively irreversible,” the group’s 1995 report said.

“I started to do some real hard visualization of possible futures,” Stephenson recalled. “In all of them—since I’m a forest guy—the forest looked pretty beat up.”

Stephenson first fell into despair. “I imagine if you’re a cancer patient, you go through something similar,” he says, “which is, it’s a complete upheaval of what you were thinking, where you thought you were going. And you probably go through all these emotional struggles and then you finally reach a point where you just say, ‘Okay, what am I going to do about it?’” In 2002, he found one outlet for his feelings: He began giving a series of talks to urge park service managers to consider the ways climate change might upset some of their long-held assumptions. Nature—if such a thing could even be defined—was never going to look like it had in the past, he told colleagues in the region, and they would ultimately have to rethink their goals.

It took a while for official park service policy heads to catch up with Stephenson, but there were others in the agency who had begun to think along these lines. Don Weeks, a park service hydrologist, had a climate change epiphany in 2002, while he and colleague Danny Rosenkrans, a geologist, were flying in a propeller plane over Wrangell-St. Elias National Park in southwest Alaska. The plane received a radio transmission about a flash flood roaring down the Tana River at the center of the park, and Rosenkrans “tells me to get ready to see something that’s going to blow my mind,” Weeks recounted.

As they approached the headwaters of the Tana, Weeks gaped at the sight of a 3-mile-wide glacial lake that had split open in one night and dumped its contents downstream. The lake had been stable for about 1,500 years until 1999, when it ruptured for the first time. When Weeks saw the lake collapse, its second occurrence at that point, it was “the most phenomenal thing I’ve ever seen in my life,” he said.

The whole tableau—the empty lakebed scattered with icebergs the size of houses and the engorged river below full of floating tree trunks ripped from the ground by flash flooding—stunned him. “I mean it was the apex of my field work as far as just seeing that level of change and the danger associated with that, the rawness of it,” he recalled recently. “To top that, I got to be standing at the edge of a volcano while it’s going off, I guess.” It was the most memorable event of his entire career. Suddenly, climate change was real to Weeks in a visceral way, and he was fascinated.

In 2010, he took a temporary post with the park service’s newly created Climate Change Response Program that eventually morphed into a full-time job. Here he encountered a group of scientists who were grappling with problems the park service had never before contemplated. For inspiration, they had turned to a strategy first hatched by the 20th-century futurist Herman Kahn, the man who inspired Stanley Kubrick’s dystopian comic film “Dr. Strangelove,” and who helped the U.S. Armed Services plan for the possible outcomes of global nuclear war. One of Kahn’s tools, “scenario planning,” has since become a popular means for business leaders to anticipate futures that are wildly different from the ones they always assumed lay down the road.

Scenario planning is like a role-playing game. You start with a scenario informed by both science and intelligent conjecture. Then you write speculative narratives about what could happen—akin to science fiction. In a national park, thinking the unthinkable sometimes means envisioning the demise of the very things you are devoted to protecting. It also means reckoning with national and local politics: What happens when the political tide turns away from both the science of climate change and the values of the National Park Service?

In a 2011 scenario planning workshop in Anchorage, Alaska, one group of scientists and park managers wrote a scenario that seemed part-warning, part-gallows-humor, in which a family of Alaska Natives tossed a faded park sign into a campfire and watched “the last letters of ‘Bering Land Bridge National Preserve’ turn black and disappear.”

The story implies a situation so dire that the park either is barely functioning or ceases to exist (though when I contacted Jeff Mow, one of the workshop’s participants and now the superintendent of Glacier National Park, he said that story was a reflection on how locals might regard the park and wasn’t intended to sound its death knell). Such bleakness may speak to the level of anxiety felt across parts of the park service. But the ultimate purpose of writing such scenarios is to avoid the worst case by considering options ahead of time.

In 2012, a group of staff from Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks, including Stephenson, gathered at a conference center in the Sierra Nevada foothills with scientists and experts from the U.S. Forest Service, the Bureau of Land Management, state agencies, and academia. Armed with maps, large sheets of tracing paper, and a set of colorful markers, they sat down to play the game.

They considered different ecological and social-political scenarios—in which, say, there was more or less rain and snow, the public was on board with their work or illegally stealing water from the park, and federal policymakers either offered little or a great deal of support. The players fleshed out the details of their scenarios—tree die-offs, insect infestations, cuts and boosts to the park budget—then made their moves. Over the course of the game, an imaginary fire rose up from the dry forest below the park and raged through the sequoia groves. The players envisioned what would happen next. What had they won and lost because of climate change, fire, and drought?

It was still early in the life of the drought, and “we didn’t know it was going to be the most severe drought in at least 120 years,” said Koren Nydick, science coordinator for the two parks. “We did not expect some of the things in our scenarios to actually happen so fast.”

As the drought wore on, Stephenson became especially concerned about what would happen to the young sequoias. He periodically patrolled Giant Forest, 1,000 feet above his research plot, looking for signs of damage. He had long thought climate change would hit the sequoia seedlings first, and in the fall of 2014, he crept through the forest on his knees, his hands covered with dust, eye-level with the dainty, baby sequoias sprouting like small Christmas trees at the feet of their behemoth parents. He paused at the base of a massive sinewy trunk, took a breath, and turned his gaze skyward. There in the crown of a full-grown sequoia he saw tufts of brown, dying leaves. “I looked up and went, ‘What the hell is going on?’” he says.

That same season, Stephenson and a field crew from the USGS surveyed the sequoias in several groves, looking for more signs of dead leaves. Park managers braced for bad news. While a number of media outlets ran stories speculating whether the old trees might ultimately keel over, in the end, only about 1 percent of old sequoias lost more than half their leaves. Most of those dropped their brown leaves that season and then greened up the next as if nothing had ever happened.

The next year, after an exceptionally snow-deprived winter, a blaze named the Rough Fire ignited in the desiccated slopes of Sierra National Forest, just west of Kings Canyon National Park. It devoured Kings Canyon Lodge, a rustic wood-frame building that hosted a burger-and-ice-cream restaurant, and ascended into Grant Grove, the dwelling place of another famous assemblage of sequoia trees.

In parts of the grove, the flames burned hot and high, seared the crowns of trees and killed off most of them, including some old sequoias. But when the Rough Fire reached the part of the forest where the park service had carried out prescribed burning over the decades, it quieted, and many of the big trees there were spared. Just as they predicted, drought and wildfire had taken a toll, but their work in the forest had saved some of the trees—and that offered some hope.

**********

In the past three years, the Climate Change Response Program has surveyed scientists and managers in the parks about climate change. All over the country, hundreds of units in the National Park Service are facing unusual situations stirred up by climate change—and in some cases, the need to act on these directly contradicts park policy on what is “natural.”

Some parks are even discussing radical interventions in the wild that the agency would never have tried in the past. Glacier National Park, for instance, has experimented with loading bull trout into water containers and carrying them by backpack to lakes at high-elevations, where they might survive if the heat becomes unbearable for them elsewhere in the park—a strategy called “assisted migration.” In-house, the agency jokingly came up with the name “gnarly issues,” from surfer jargon, to describe these situations.

One of the gnarliest issues came up a year later in the Pacific Northwest. In May 2015, during one of the driest springs on record in Olympic National Park, a lightning strike lit a fire in the remote old-growth Queets rainforest. It kept burning through a record-breaking hot summer until September, scorching 2,800 acres. In August, lightning set another 7,000 acres ablaze on the west side of North Cascades National Park. The fire leaped across the Skagit River, jumped a highway, and charged up the mountainsides. It rushed toward the park visitor center, forcing tourists to flee.

Though large fires are common in dry regions like the Sierra Nevada, they rarely occur in wet forests like these. Some trees don’t deal well with fire, and in places like rainforests and alpine forests, pervasive dampness keeps blazes from traveling far. Only when the air is uncommonly dry and hot and the wind steady can a fire grow in size here. It then often kills nearly everything in its path. Fires like this tend to come only every few centuries to patches of forest on the wet, west side of the Cascade Range or Olympic Mountains. But these two fires, the largest west-side burns in either park’s history, had blazed up in the same season. Were they a warning sign of hotter, more fire-prone seasons to come?

On a hot day in August of last year, I donned a heavy black hard hat and followed Karen Kopper, her lead field technician, aptly named Cedar Drake, and a crew of four field researchers into a dusty, blackened section of forest in North Cascades National Park. Kopper, a petite, sandy-haired woman with a serious demeanor, works for North Cascades as a fire ecologist. She’s also writing a history of forest fires of the Pacific Northwest. But until 2015, she’d never seen a blaze burn so large on this side of the park.

We walked into what used to be a lush, dense, old-growth forest: home to centuries-old stringy-barked cedars with sinuous roots, towering Douglas firs, and hemlocks. Before the fire, the ground was a carpet of moss, huckleberry bushes, and sword and bracken ferns, and was usually sodden with rain for about nine months of the year or more.

That day, the dirt beneath our feet was as loose as beach sand. The fire had eaten up most of the organic matter and left the soil full of ash. The forest floor was nearly bare, except for clumps of charcoal and a few short stems of bracken fern and fireweed, a hot pink flower whose seeds often blow in and germinate just after a conflagration. I spotted a few green branches at the top of a thick-trunked hemlock, but Kopper told me the tree probably wouldn’t make it. Hemlocks don’t like fire. Many of the trees above us were already dead. When we heard a pop from the upper canopy, Kopper and Drake were both startled and exclaimed, nearly in unison, “What was that?” They looked up warily. No one wanted to be in the path of a collapsing dead tree.

Drake and his crew fanned out. They tied strips of pink plastic tape to the trees to flag the edges of a circular research plot with a nearly 100-foot diameter. Then each person stood in a different section of the plot and shouted out an estimate of how much forest was dead and how much was still alive. Drake recorded their figures in a chart. He noted that the soil was almost completely burned through, and the small trees and shrubs were nearly all gone. Over the entire area of the fire, Kopper estimated that more than half of the big and mid-sized trees had died. In some parts of the burn, more than 70 percent of the trees were toast.

Though the park service regularly sets fires in its forests to mimic the natural fires of the past, it hardly ever meddles in the aftermath of a fire like this: to do so would be “unnatural.” Historically, the forest would have grown back slowly on its own, over about 75 to 100 years. But climate change may make these fires more commonplace. A forest like this can’t grow back if fire returns too often. Kopper wonders if this place will ever be the same.

Three years ago, even before these large conflagrations, she suspected west-side fires could become a conundrum for this park and told the agency so in her response to their survey. In 2015, the park service asked her to research this particular gnarly issue (now a semi-official phrase among park service scientists) further.

She and three other scientists have since written up an analysis describing the many quandaries and questions they were wrestling with. Should foresters try to keep the landscape as it would have been before the temperatures warmed—irrigate the forest, set up firebreaks, and aggressively replant moisture-loving trees and plants every time they burn down? Or should they try to revamp the place by transplanting species from, say, the rain-shadow side of the mountains where fires are common? Are any of these things in line with the park service’s long-held ideals about nature, and if not, what would the agency need to do now?

What is truly natural or unnatural anymore?

**********

After we left his research plots, Stephenson took me to Giant Forest, and we parked the car in the visitor lot. I caught my breath at the sight of the giant sequoias—muscular, poised, and shocking in their scale and beauty. As we walked, he periodically pulled out a monocular, like a mini-telescope, and stared at their upper leaves. The longer we stayed, the giddier he became, like a kid playing in the woods. He delighted at the sight of a woodpecker. “What a cute little bird,” he said and stared for several minutes. Nearby, he spotted a cluster of sugar pines with full, green crowns. “I’m feeling kinda happy,” he said, “It looks like this group hasn’t been hit by beetles yet.” When we descended from a rock outcrop near the visitors’ center, he slid down a stair railing, grinning.

He said he thought the effects of climate change “will come in bursts” like this drought. Things would look fine, then all at once, trees would die, infernos would rage, insects would throng. So far, the sequoias were mostly doing fine. In 2015, Stephenson spotted 11 that had turned brown and died altogether, still standing. Previously, he had only witnessed the death of two standing sequoias in his entire career. Still, “it doesn’t concern me,” he said. Not yet.

But in the long term, “we don’t know that the sequoias will be okay,” he admitted. He had suggested that the managers of Sequoia and Kings Canyon consider planting a few sequoias at a higher elevation above Giant Forest, where they might stay cooler as the climate warms. He knew a decision like that could be contentious. But young sequoias don’t produce seeds for several years, so Stephenson figured the park would have a while to figure out whether it was a big mistake.

“I can see [the park service] being sued for not doing enough in the face of climate change, and then I could see being sued for doing things in the face of climate change,” Stephenson told me. “In the end, I guess, the courts sort it out, but boy, in the meantime what do you do? Do you get paralyzed and not do anything?”

It’s still not entirely clear how President Trump’s rejection of the science of climate change might affect the national parks. Stephenson told me longstanding rules prevented him from talking politics, even when they directly affected his work. Some employees within the park service also turned down my requests for comment. At the moment, there’s no clear, agency-wide decree that would force their silence on such touchy subjects, but from some, I sensed discomfort and even fear that sharing their opinions might be risky.

Weeks, the park service hydrologist, suggested that scenario planning might have prepared some parks for the new political regime by prompting them to imagine life with both more and less supportive federal leadership. “So if a park has played through this and kind of rehearsed for this, they’re in a better position, because it looks like we’re changing to a different kind of mindset,” he told me in December.

Eight months later, he felt it was still too early to tell how the administration might deal with climate change in the park service. “I do have some concern,” he said, “but I haven’t seen it play out, and I’m always trying to be optimistic.” Glacier National Park Superintendent Jeff Mow said no new political winds had yet blown into his park and affected its immediate management, but he felt that the administration couldn’t forever disregard the impacts of climate change. “There’s things going on around us, like extreme weather events, that can’t be ignored” he said.

For decades, the national parks have been the country’s environmental conscience, the places that reminded us what nature is supposed to look like and who we are by extension. “Certainly, if ever the American psyche survived losing the parks,” the historian Alfred Runte wrote in his book National Parks: The American Experience, “the United States would be a very different country indeed.”

For at least the next three and half years, the problems faced by the park service could get gnarly indeed. Even if the federal government tries to suppress research, education, or public outreach on climate change, there’s no getting around what’s already happening in the parks. Even if they don’t “go rogue,” national park staff will continue to find themselves on the frontlines of a series of ethical dilemmas—about science and the future of nature, which species to save or to relocate, and when and whether to speak out about the changes they are witnessing every day in the American landscape.

In May, Stephenson told me he saw fresh signs of death among the trees while walking through his research plots, even after a wet winter. The White House had just unveiled a budget proposal that would slash the Department of Interior’s funding by 11 percent and lay off more than 1,200 park service employees. Given this, I asked Stephenson if he and his colleagues in this national park and others across the country will be able to keep up with the demands posed by climate change—and the colossal, unprecedented experiment unfolding in front of them as the heat turned up?

He said he couldn’t comment.

Madeline Ostrander is freelance science journalist based in Seattle. Her work also appeared in The New Yorker, Audubon, and The Nation, among other publications.

For more articles like this, please visit undark.org