The Naturalist Who Inspired Ernest Hemingway and Many Others to Love the Wilderness

W.H. Hudson wrote one of the 20th century’s greatest memoirs after a fever rekindled visions of his childhood.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/8d/41/8d412fd8-fdd8-476f-843d-9064663c4bcf/may2017_b07_argentina-wr.jpg)

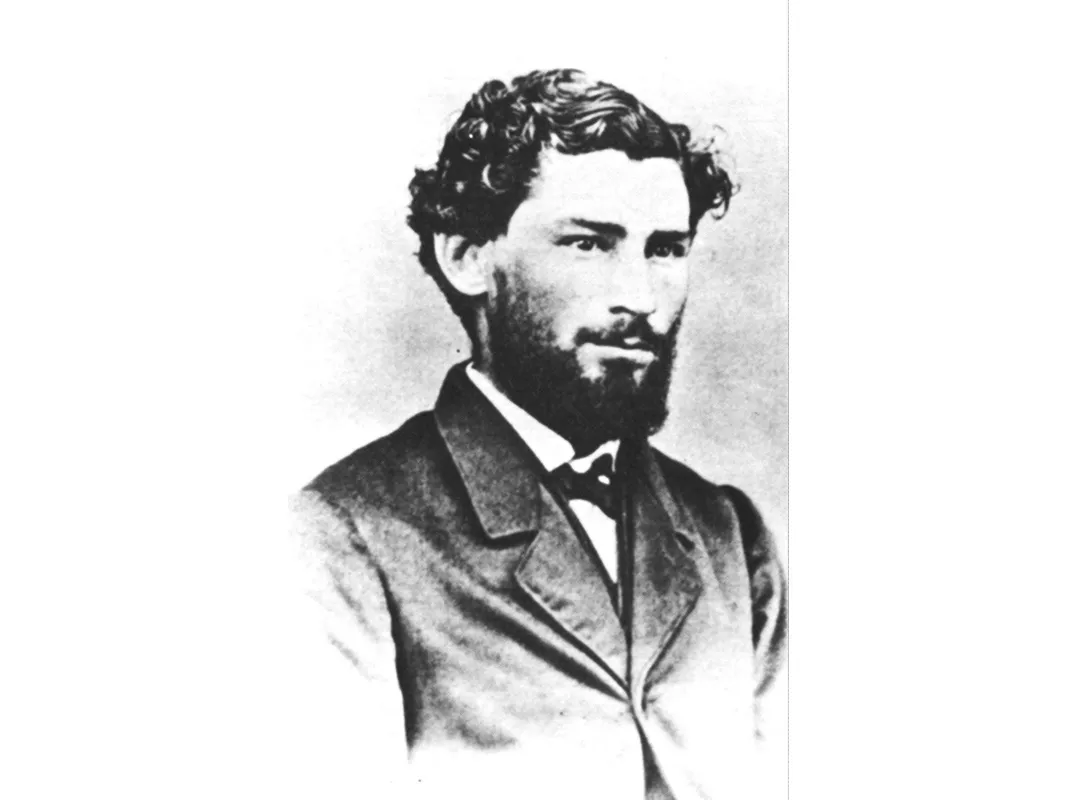

William Henry Hudson earned his name as a naturalist, novelist and best-selling author of love letters to the South American wilderness, yet no one can quite agree on what that name should be.

His parents were American—New Englanders who immigrated to Argentina in the 1830s to try their hand at sheep farming. But in the United States, this one-time collector of Latin American bird specimens for the Smithsonian Institution is generally filed under “W. H. Hudson,” and next to Forgotten. In Japan, his passionate memoir of youth, Far Away and Long Ago—composed 100 years ago, in 1917—has traditionally been used to teach English. Since the book’s publication in 1918, students there master pronunciation of the name William Hudson. In England, where Hudson lived out a long, gray exile penning books and disputing Darwin himself on woodpeckers, he was called a friend by Joseph Conrad, “an eagle among canaries” by the novelist Morley Roberts and more “a thunderstorm” than a man by one female admirer. The London Times, in its obituary of Hudson, who died in 1922, judged him “unsurpassed as an English writer on nature.”

But in Buenos Aires, the guys who fetch me at a coffee shop near the presidential palace refer to him as Guillermo Enrique Hudson, pronounced “Hoodson.” The driver, Ruben Ravera, is director of the Amigos de Hudson; in the passenger seat is Roberto Tassano, the group’s treasurer. Our goal that morning was to travel well outside Buenos Aires, into the flat grasslands called the pampas, which make up much of Argentina, to see Hudson’s house, which still stands. Today it is part of a 133-acre ecological reserve and park, with a small museum devoted to the origins of one of the 19th century’s greatest mythopoetic geniuses.

A child of the saddle, Hudson—by any name—was born in Argentina in 1841. He was a naturalist and ardent birder whose writings on South America—about plants, animals, rivers, and men and women—echoed the transcendental movement of North America, exemplified particularly by the works of Thoreau, and struck a deep chord among readers in Europe. Hudson felt, with the sensual keenness of childhood, that the pampas were a paradise, a deep spring of mystery and revelation. In books that ranged from The Naturalist in La Plata to Idle Days in Patagonia, his gift was seeing the glory in the everyday, like the sounds of backyard birds (he compares their calls variously to bells, clanging anvils, tight guitar strings, or a wet finger on the edge of glass).

He was a master at apprehending the rhythms of nature, and reflecting them back to readers. His vision of Argentina was grand—a limitless plane of possibility, where the pleasures of nature were only sharpened by hardship. Argentines have a complicated relationship with rural life, often lionizing the city, but the 1950s Argentine writer Ezequiel Martínez Estrada championed Hudson’s books, finding in them an antidote, an illumination revealing the hidden beauties of the sparse terrain. It took an outsider to make their own country familiar.

**********

Racing away from Buenos Aires with Ravera and Tassano that morning, I discovered that Hudson’s name is simultaneously forgotten and evoked in the region south of the capital where he lived. In quick succession, we saw a “Hudson” shopping mall, a Hudson train station and a gated community called Hudson. We passed a highway sign with a big arrow pointing to HUDSON, a town not near the author’s home. About an hour outside the city we pulled to a halt at a tollbooth, named the Peaje (Toll) Hudson. Tassano handed over 12 pesos, and we sped onward.

Argentines didn’t read the books of their ardent champion, Tassano noted, simply calling Hudson a “prestigious writer,” which he joked is the local dialect for “unread writer.” No one was sure whether to claim him as a native.

Hudson felt conflicted about the question himself. He was born in Quilmes, not far from that tollbooth we had just passed. But Hudson was raised in Argentina by Shakespeare-quoting American parents, and he lived out his life in England, writing in English.

We arrived down a muddy lane and entered a white gate, kept locked in a vain attempt to stop thieves from entering the William H. Hudson Cultural and Ecological Park, a nature reserve protected by provincial decree. It’s managed by the Friends of Hudson, Ravera’s defiant band of the author’s admirers. For many years, Hudson’s own grandniece led the group, which has struggled at times to preserve the property.

As we walked around the grounds, Tassano pointed out that the soil here in the pampa húmeda is black and rich, “the most productive in the country.” But Argentina seemed to alternate “from prosperity to crisis, never regular,” he said, a cycle that affected the Hudson family as well. And the Friends of Hudson, too. The group has modest public funding, but spends steadily on maintenance, hosting school groups and paying a handful of local staff. They are “mendicants” when it comes to a budget, Ravera told me, alleviated only by the occasional windfall, like the day the Japanese whiskey maker Suntory called in 1992 and, without warning, donated $270,000 to buy up more of Hudson’s land for the reserve and to construct the small library.

Suntory? Yes, Japanese readers could be said to count as Hudson’s most devoted fans, and among the few foreign tourists to routinely show up at the house. The measured pace and beautiful imagery of Far Away and Long Ago has made the English language come alive for generations of Japanese students, and while the themes are universal, Hudson’s animistic embrace of nature “cuts to the core of the Japanese heart,” Tassano said.

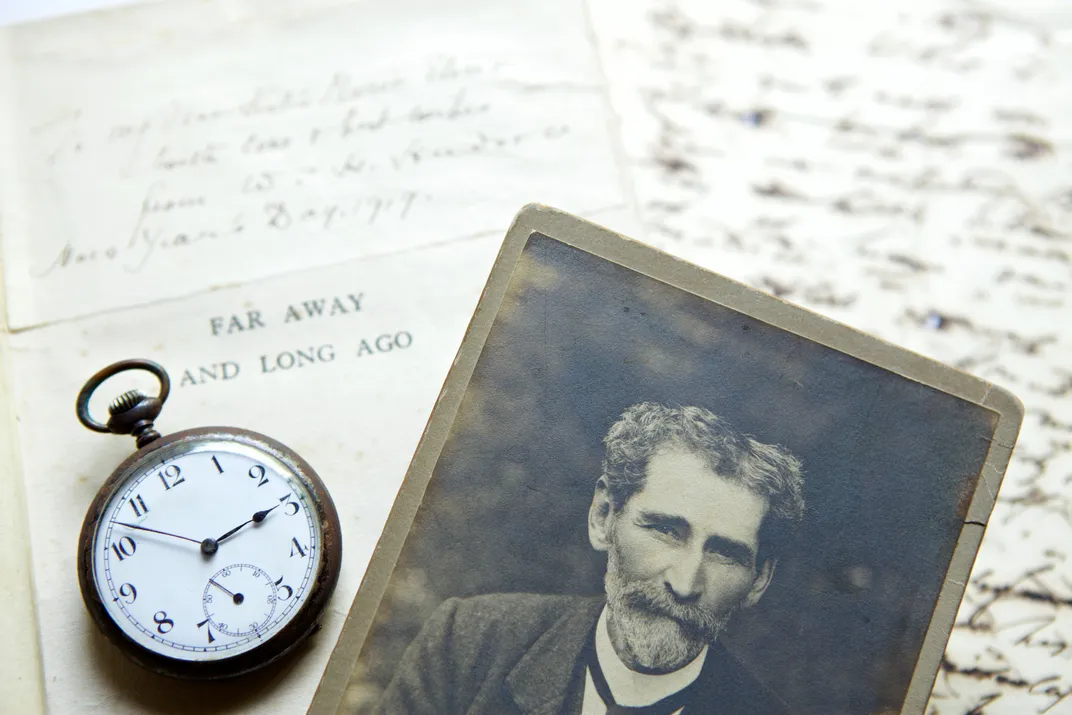

Hudson’s house is a simple three-room building of rock-hard adobe bricks, the thick walls whitewashed and topped with a beam and shingle roof. The small proportions of the house prove what is evoked so profoundly in Far Away and Long Ago: that there is an unlimited kingdom in even a small space or patch of ground. It was only seven years after Hudson’s death in England that a Quilmes doctor tracked down the naturalist’s house, and 12 years later, in 1941, the Friends of Hudson was founded in Buenos Aires. The group eventually secured the property, which gained protected status in the 1950s. In the house, dedicated to Hudson’s life, glass cabinets hold specimens and models of the colorful bird life Hudson cherished above all, including the plush-crested jay, the checkered woodpecker and the brown-and-yellow marshbird. Hudson, for whom the flycatcher Knipolegus hudsoni is named, also collected hundreds of specimens for the Smithsonian. A small A-frame library stands nearby, welcoming visitors and displaying Hudson’s pocket watch beside an extensive collection of works on the South American flora and fauna beloved by Hudson.

Hudson’s fields and trees are what people come to see, though the prospect of walking just a few hundred yards into the ecological reserve is enough to darken Tassano’s mood. He makes me wait as he summons a provincial police officer to accompany us. The policeman, named Maximiliano, tails us into the waist-high pampas grass, swatting at mosquitoes, a pistol on his hip.

“Nothing is going to happen,” Ravera explained, “but...”

Hudson’s old farmland, once a symbol of rural isolation, now abuts a settlement of low brick houses, a dense warren of newcomers in what Tassano called “one of the poorest, most pauperized areas of the capital province.” Our police escort had been on patrol almost directly across the street from Hudson’s house.

We walk into the fields and see in quick succession much of what Hudson would have observed. A large chimango hawk, brown and white, settles into a bush and mocks us before buzzing away. Then there is an hornero, a reddish bundle of feathers that is native to the pampas. Among the plants is Pavonia septum, whose small yellow flower pleased Hudson’s eye. After just five minutes we come to the fragrant creek that Hudson wallowed in as a boy and that he wrote about in the opening of Far Away and Long Ago. The waters were still very much as he described, a narrow but fast-moving and deep channel, “which emptied itself in the river Plata, six miles to the east,” the brown water holding catfish and eels.

In an 1874 letter in the museum’s collections, Hudson described birds as “the most valuable things we have.” But not everyone in the pampas values the treasures around them. At the stream we find that two of the modernist metal sculptures, recently placed by the Hudson museum to call attention to the beauty of the pampas, have been knocked into the water, an act of vandalism. As mosquitoes rise from the tall grass, Tassano nods to the houses across the road. The population of the local area—called Villa Hudson—had burgeoned in a decade, he says. Many of the newcomers were originally migrants from rural areas who had tried urban Buenos Aires, but found it too expensive. They retreated to the farthest fringes of the province and built their own simple houses.

Most of the residents in Villa Hudson are law-abiding, Ravera said, but high unemployment and poverty have bred trouble, and young drug addicts had probably hurled these statues into the stream. During the 1990s, the Hudson library was robbed twice. First, petty thieves took cellphones and other electronics they found in the library, but then the robbers grew more sophisticated, stealing Hudson’s signed first editions and other rare works from the shelves. Some of them were worth thousands of dollars; Tassano knows because he eventually found the rare copies for sale in a Buenos Aires bookstore. The property was returned.

**********

In Hudson’s day, of course, there was no neighborhood. Much of his memoirs are taken up with the themes of joyous but solitary wanderings, and the tiny circle of human contacts his family enjoyed, with just a few fellow farmers on the horizon, and “close” acquaintances living days away. His mother kept a 500-volume library, but Hudson was barely educated, and his passionate embrace of nature was driven by solitude. When Hudson made journeys to Buenos Aires, it was two days on horseback. Ravera had driven the distance in about an hour.

There are other threats to the reserve. Fields of soy, Argentina’s boom crop, are now planted right up to the very borders of the ecological park, and aerial spraying of the crop has twice killed off the insects on which Hudson’s beloved birds depend. Hudson himself, toward the end of his life, decried the despoiling of the pampas, lamenting acerbically that “all that immense open and practically wild country has been enclosed in wire fences and is now peopled with immigrants from Europe, chiefly of the bird-destroying Italian race.”

Today, even the fields are under pressure. In January 2014, a portion of Hudson’s old grassland was abruptly occupied by squatters from across the road in Villa Hudson. They were organized, and arrived carrying building supplies to claim lots amid the fields. This kind of land invasion can become legal in Argentina, if it endures for more than 24 hours, and involves “unused” land, a term that overlaps neatly with the definition of an ecological reserve. Tassano raced out to the property that morning and summoned police, who evicted the squatters the same day. The ecological park was restored. Yet Tassano was not without sympathy for the people, who were impoverished and had to live somewhere. The damp grasslands around the capital, the landscape that had originally defined Argentina, are disappearing under a wave of humanity. This demographic pressure is “the sword of Damocles over our head,” Tassano said.

Out in the fields that afternoon, nothing happened, in the best way. Wandering in the landscape where Hudson took his first steps, we come across a few of the last ombu trees that had lived in his day—enormous and sheltering, with wide trunks and rough bark. Other trees he studied—the spiny and aromatic Acacia caven, the algarrobo with the hardest wood in Argentina—are scattered around the property, which holds pockets of forest punctuating wide fields of swaying pampas grass.

Away from these fields, Hudson’s very existence seemed to fade. He was merely “a stranger in the city,” Tassano noted, when he made his forays into Buenos Aires. He left for London in 1874 at age 32, hoping to be near the center of scientific and literary life. The family had not prospered; Hudson’s parents had died and his several siblings had scattered to seek their fortunes. But without connections—he had few acquaintances, one a fellow naturalist in London—Hudson at first found only penury and illness, a bearded figure in threadbare clothes, impoverished and solitary, attempting to eke out life as a writer. Searching for the truth of nature, he often wandered the windy downs of the Cornish coast, choosing deliberately to be whiplashed by storms and soaked by rains, like a Taoist monk on retreat.

He published articles in British ornithology journals and submitted natural history pieces to the popular press. “It occasionally happened that an article sent to some magazine was not returned,” he recalled, “and always after so many rejections to have one accepted and paid for with a cheque worth several pounds was a cause of astonishment.”

His novels—The Purple Land, centered on a young Englishman’s exploits in Uruguay, set against a background of political strife and first published in 1885, and Green Mansions, a bewitching account of doomed lovers and an eden lost in the Amazonian rainforest, published in 1904—were largely ignored at first.

A measure of stability came when he married his landlady, Emily Wingrave, a decade or so his senior. He became a naturalized British citizen in 1900. The following year, friends succeeded in getting Hudson a modest civil service pension, “in recognition of the originality of his writings on Natural History.” His fortunes improved. Turned out in linen collars and tweed suits, he trotted around London parks on a black mustang named Pampa. He once burst into tears, caressing the horse and declaring that his life had ended the day he left South America.

But his intense longing for the landscape of his childhood was not wasted. In 1916, when he was 74, a bout of sickness—he had long been plagued by cardiac palpitations—left him bedridden. “On the second day of my illness,” Hudson recalls in Far Away and Long Ago, “during an interval of comparative ease, I fell into recollections of my childhood, and at once I had that far, that forgotten past with me again as I had never previously had it.” His feverish state gave him access to deep memories of his youth in Argentina, memories that unfolded day after day.

“It was to me a marvelous experience,” he wrote, “to be here, propped up with pillows in a dimly lighted room, the night-nurse idly dosing by the fire; the sound of the everlasting wind in my ears, howling outside and dashing the rain like hailstones against the window-panes; to be awake to all this, feverish and ill and sore, conscious of my danger too, and at the same time to be thousands of miles away, out in the sun and wind, rejoicing in other sights and sounds, happy again with that ancient long-lost and now recovered happiness!” He emerged from his sickbed six weeks later, clutching the beginnings of the rapidly penciled manuscript of his masterpiece, Far Away and Long Ago.

He continued working through 1917, creating a time-travel odyssey, phantasmagorical and cinematic, to a vanished time and place. Some of the figures Hudson encountered on the pampas—an aimless and impoverished wanderer, the fiercely proud gauchos—take on a strange and powerful immediacy similar to the magical realism of the titanic Latin American writers Gabriel García Márquez and Jorge Luis Borges, who revered Hudson. (Borges once devoted an entire essay to The Purple Land.)

Soon, a reader is transported to the transcendent moment when a 6-year-old Hudson, trailing his older brother on an outing, first glimpses a flamingo. “An astonishing number of birds were visible—chiefly wild duck, a few swans, and many waders—ibises, herons, spoonbills and others, but the most wonderful of all were three immensely tall white-and-rose-coloured birds, wading solemnly in a row a yard or so apart from one another some twenty yards out from the bank,” Hudson wrote. “I was amazed and enchanted at the sight, and my delight was intensified when the leading bird stood still and, raising his head and long neck aloft, opened and shook his wings. For the wings when open were of a glorious crimson colour, and the bird was to me the most angel-like creature on earth.”

Hudson’s genius, wrote the novelist Ford Madox Ford, in Portraits From Life, a series of a biographical sketches published in 1937, lay in his ability to create a sense of complete, incantatory immersion. “He made you see everything of which he wrote, and made you be present in every scene that he evolved, whether in Venezuela or on the Sussex Downs. And so the world became visible to you and you were a traveller.”

Even so, as the novelist Joseph Conrad observed, Hudson’s quicksilver talent defied easy categorization. “You may try for ever to learn how Hudson got his effects,” Conrad once wrote to Ford, “and you will never know. He writes down his words as the good God makes the green grass to grow, and that is all you will ever find to say about it if you try for ever.”

The poet Ezra Pound tried to get at it as well, citing the mysterious force of Hudson’s “quiet charm.” Hudson, wrote Pound, “would lead us to South America; despite the gnats and mosquitoes, we would all perform the voyage for the sake of meeting a puma, Chimbica, friend of man, the most loyal of wildcats.”

Ernest Hemingway, too, fell under the spell of Hudson’s work. In The Sun Also Rises, Jake Barnes assesses the seductions of Hudson’s Purple Land, “a very sinister book if read too late in life. It recounts the splendid imaginary amorous adventures of a perfect English gentleman in an intensely romantic land, the scenery of which is very well described.”

**********

Accident had played a role in Hudson’s achievement from the very start. As a young man, he had reached Patagonia, on the expedition during which he would identify the flycatcher named after him. Swimming his horse across the Río Negro, he inadvertently shot himself in the knee. He was forced to spend months convalescing alone in a remote shepherd’s cabin. His Idle Days in Patagonia (1893) is the fruit of turning this misfortune to wry advantage; unable to walk, he was forced to study flora and fauna at close range. Tossing crumbs out the front door, he let the birds visit him, and so discovered and documented Knipolegus hudsoni. He discoursed with stunning acuity on the habits of mice, and wrote as easily about the many tools that lined his shed. He awoke one morning to find a venomous snake in his sleeping bag—and, in a twist worthy of Edgar Allan Poe, makes the reader wait almost as long as Hudson did for the snake to wake up and crawl away.

After visiting Hudson’s house, I flew down to my own Patagonian exile. The plane passed high over the Río Negro, Patagonia’s traditional beginning, and took me farther south, to the Chubut Valley, an isolated landscape Hudson might still recognize. I had seen the valley in 1996 and, taken with its quiet, I began returning, more and more frequently. Eventually I bought a small plot of land and built a cabin. On this trip I spent a week there, reading Hudson and enjoying many of the dubious charms he found in the countryside: a drafty house, a tranquil wilderness plagued by mice and graced with enormous quantities of nothing. There was the rural sociability Hudson would recognize—a few old gauchos grazed their spare horses on my land, and sometimes I could walk over a hill to have coffee with a welcoming Italian couple who had settled there. Reading Idle Days, I felt Hudson reacting to the Patagonian landscape I’d come to know more deeply than I realized. Up in the foothills of the Andes, he observed, there were fewer birds than one found down in the river valleys. I recalled that Hudson had mentioned the presence of “paraqueets,” or the Patagonian parakeet, a frequent visitor to my property. Entire squadrons would land in the high branches of my pine trees, a clumsy racket of wings that sounded like an airborne assault. My only other visitors were a white horse, which patrolled the ground slowly at dusk, munching my grass, and later, the loud hoot of a pygmy owl reigning over the nocturnal hunting grounds.

All was quiet, cozy and familiar, just the way Hudson liked it. His world lives, still.

Related Reads

Far Away and Long Ago: A History of My Early Life

Green Mansions: A Romance of the Tropical Forest

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/SQJ_1610_Cuba_Contribs_04-WR.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/SQJ_1610_Cuba_Contribs_04-WR.jpg)