New Desert-Dwelling Pterosaur Unearthed in Brazil

A massive bone bed is already yielding insights into the flying reptile’s lifestyle

:focal(331x226:332x227)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/4a/09/4a0933b9-4312-4c3e-981f-9d036fbc9ee4/foto_de_pagina_inteira_001.jpg)

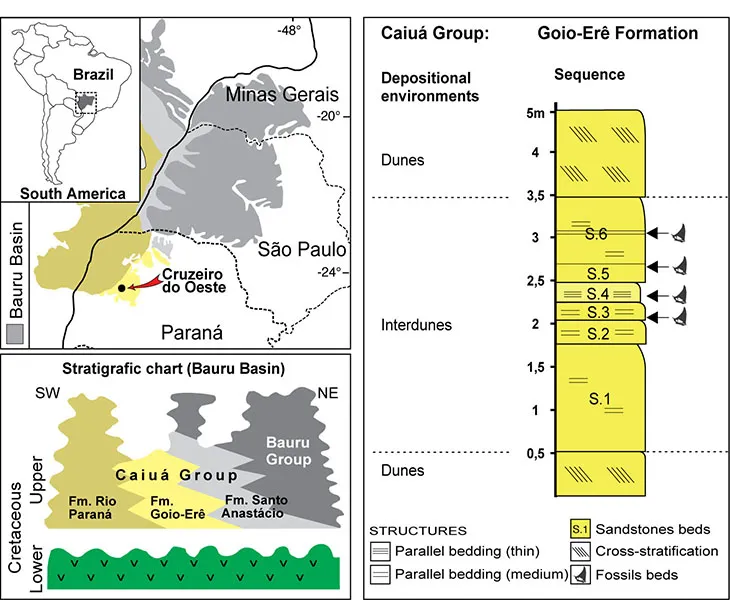

Once upon a time in southern Brazil, toothless dragons ruled the skies. A Brazilian research team has discovered fossils from a new species of pterosaur—the distant, flying reptile cousins of dinosaurs—that lived 75 to 87 million years ago in the ancient Caiuá Desert.

The huge bone bed, outside the city of Cruzeiro do Oeste, contains hundreds of specimens of the novel species, dubbed Caiuajara dobruskii. The discovery provides a window into the pterosaur world, revealing that these animals were quick to take flight after birth, and that they may have been social creatures that nested in big, bustling communities.

Geologic evidence puts the bone bed in the late Cretaceous period and suggests that pterosaurs lived near small lakes in the surrounding desert, as well as along the coast of northern Brazil. “These animals lived in rare humid regions among the dunes, like oases,” says Luiz Carlos Weinschütz, a geologist at the Universidade do Contestado’s paleontological center in Mafra, Brazil.

Local Alexander Dobruski and his son João discovered the site while digging a runoff ditch back in 1971. In 1975, they sent off fossil samples for scientific study, but the bones sat in storage for the next three decades. In 2011, Weinschütz and his colleague Paulo César Manzig, a paleontologist at the Universidade do Contestado, stumbled upon them while doing research for a book on Brazilian fossils. The researchers traveled to Cruzeiro do Oeste to literally do some digging.

“When we arrived at the discovery site, the bones were visible—many pterosaur bones right in front of my eyes,” recalls Manzig. “It was one of the most exciting moments of my life.”

After carefully excavating 66 square feet of the sandstone site, the researchers uncovered at least 47 individual pterosaurs, including many juveniles. The reptiles had wingspans of 2.1 to 7.7 feet, ranging from the size of a model airplane to an albatross. They also lacked teeth and may have been frugivores, relying on a heavy fruit diet.

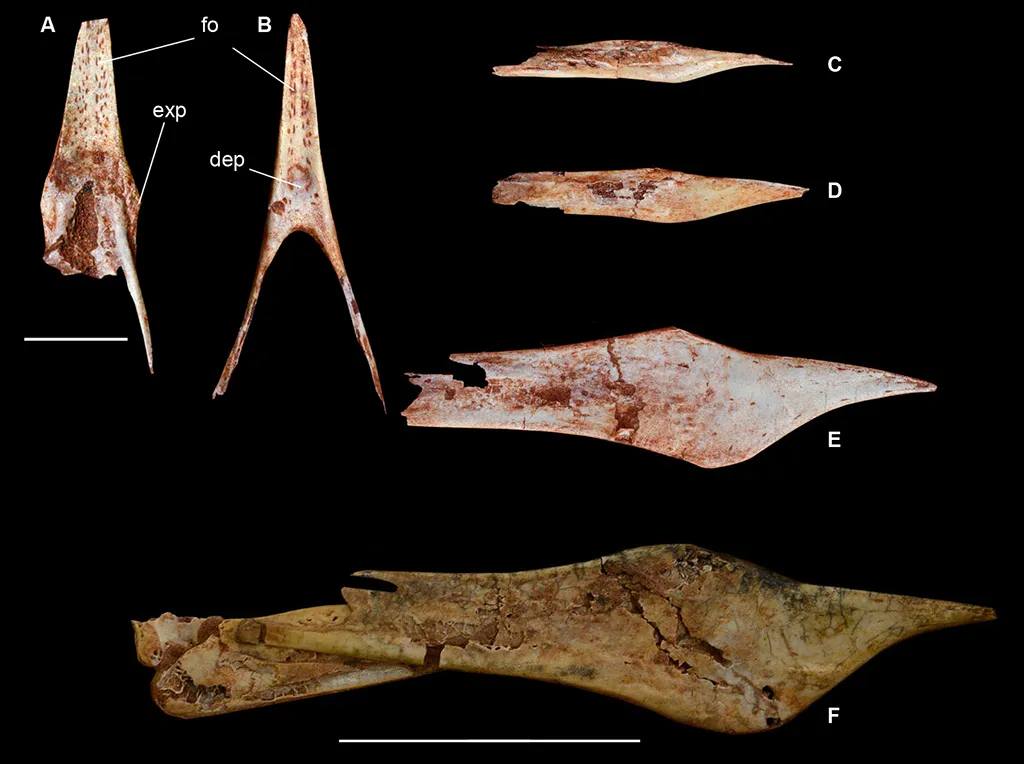

By analyzing the shapes of the fossilized bones and the presence of different anatomical characteristics, the researchers were able to figure out what branch of the pterosaur family tree gave rise to these particular creatures. A few clues then led the team to conclude that they were looking at an entirely new species. For one, all of the individuals had a unique divet in the jaw and a bony ridge above the eye. Like many other winged reptiles, this group of pterosaurs also had unique head crests. Adults had steeper, larger crests, while juveniles had smaller, less-sloped ones.

“Some researchers think that the crests were only display structures, others envision them as being a form of sexual dimorphism—males have them, females don’t. Personally, I think it was a mix of different functions,” explains Alexander Kellner, a paleontologist at the Museu Nacional in Rio de Janiero and another co-author on the study.

With both adults and young at the site, the researchers gleaned some insight into the pterosaurs' growth cycle. Adults and juveniles don’t show huge differences in their skeletons and wings, so the pterosaurs likely started flying at a young age. As a result, they probably didn’t require a lot of parental supervision and experienced a more reptilian upbringing, more like crocodiles or turtles than mammals or birds.

Finding such a high volume of these creatures is rare, and the fact that they were discovered clumped together within the same 5-foot rock layer points to the animals living and dying in the same place. Along with other recent pterosaur finds, it paints a compelling picture of pterosaurs nesting together and living in colonies. “This certainly indicates that at least some of these animals were gregarious,” says Mark Witton, a paleontologist at the University of Portsmouth in the U.K. “The lake that Caiuajara lived next to must have been swarming with pterosaurs.”

Others are hesitant to rule out alternative explanations. Seasonal flooding could have washed bones into the area from animals that died elsewhere. “Such mass accumulations are not uncommon and are not necessarily evidence of animals living and dying in groups,” says Hans-Dieter Sues, a vertebrate paleontologist at the National Museum of Natural History in Washington, D.C.

So what killed these particular flying lizards? Bones were mixed together and interred at different times, so multiple causes of death are probably at play. Drought and desert storms are the main contenders, though. “Any climate oscillation might have been fatal for fragile individuals,” says Weinschütz. “Sporadic storms could have carried bones to the bottom of the desert lakes.”

The ongoing excavations could yield further answers. By the Brazilian team’s estimates, the bone bed spans an area of about 4300 square feet. That’s about the size of a swimming pool, and excavators have only unearthed 5 percent of the site. Who knows what other fossilized treasures could lie cemented in sandstone?

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Screen_Shot_2014-01-27_at_12.05.16_PM.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Screen_Shot_2014-01-27_at_12.05.16_PM.png)