New Discovery of 7000-Year-Old Cheese Puts Your Trader Joe’s Aged Gouda to Shame

Previously traced to ancient Egypt, prehistoric pottery indicates that cheese was invented thousands of years earlier

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/SurprisingScience-Cheese-631.jpg)

Archaeologists have long known that cheese is an ancient human invention. Wall murals in Egyptian tombs from 2000 BCE depict cheesemaking, and Sumerian tablets written in cuneiform text seem to describe cheese as well. Our distant ancestors, it seems clear, knew about the wonder that is cheese.

Today, though, cheese lovers have cause to celebrate: New evidence indicates that the invention of the utterly delicious and at times stinky product actually came thousands of years earlier. As described in a paper published today in Nature, chemical analysis of prehistoric pottery unearthed from sites in Poland shows that cheesemaking was invented way farther back than originally believed—roughly 7000 years ago.

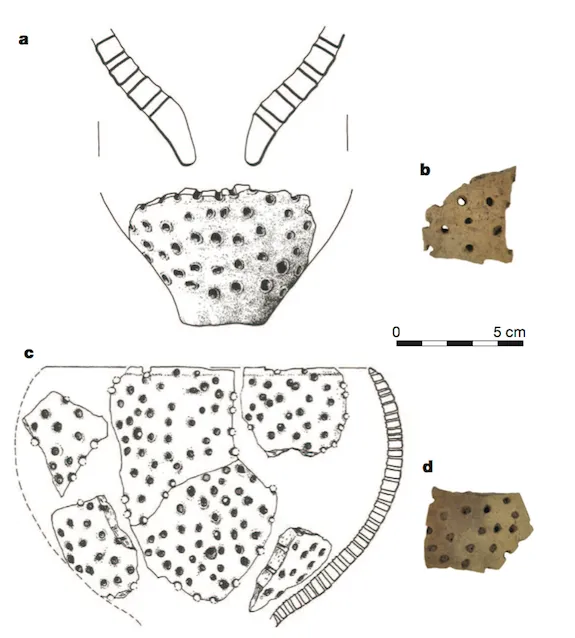

A team of researchers from the University of Bristol, Princeton and a group of Polish universities came to the finding by examining an unusual group of artifacts from the Polish sites: clay shards that were pierced with a series of small holes. Struck by their resemblance to in modern-day cheese strainers, they chemically tested the material around the holes, and were vindicated to find ancient traces of the kinds of lipids and fatty acids found in dairy products. These ceramics are attributed to what archaeologists call the Linear Pottery culture, and are dated to 5200 to 4900 BCE.

“The presence of milk residues in sieves, which look like modern cheese-strainers, constitutes the earliest direct evidence for cheesemaking,” said lead author Mélanie Salque of the University of Bristol in a statement. “So far, early evidence for cheesemaking were mostly iconographic, that is to say murals showing milk processing, which dates to several millennia later than the cheese strainers.”

Although different cheeses are made by a variety of processes, nearly all start with the separation of milk into liquid whey and solid curds. This is typically accomplished by adding bacteria to the milk, along with rennet (a mix of enzymes produced in animal stomachs), then straining out the liquid from the newly-coagulated curds. These perforated pots, then, seem like they were used to strain out the solids.

The researchers also analyzed other pottery fragments from the site. Several unperforated bowls also had traces of dairy residues, indicating they might have been used to store the curds or whey after separation. They also found remnants of fats from cow carcasses in some of the ceramics, along with beeswax in others, suggesting they were used to cook meat and sealed to store water, respectively. Apart from being capable of making a complex food product like cheese, it seems that these ancient people also created different types of specialized ceramics for different purposes.

The authors of the paper believe this ancient cheesemaking goes a long way in explaining a mystery: why humans bothered to domesticate cows, goats and sheep thousands of years ago, rather than eating their wild ancestors, even though genetic evidence indicates that we hadn’t yet evolved the ability to digest lactose, and thus couldn’t drink milk. Since cheese is so much lower in lactose than milk, they say, figuring out how to make it would have provided a means for unlocking milk’s nutritional content, and gave prehistoric humans incentive to raise these animals over a long period of time, instead of slaughtering them for their meat immediately. Making cheese also gave these people the ability to preserve the nutritional content, since milk spoils much more quickly.

That leaves one more pressing question—what did this ancient cheese actually taste like? Without abundant access to salt or knowledge of the refined heating and ripening processes that are necessary for the variety of cheese we have today, it’s likely that the first cheeses were pretty bland and liquidy. Like ancient Egyptian cheeses, these were probably comparable in texture and taste to cottage cheese, Salque and colleagues noted.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/joseph-stromberg-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/joseph-stromberg-240.jpg)