A New Paradigm for Animal Research: Let Them Participate

In labs around the country, researchers are realizing that in many cases, it’s easier to work with animals than against them

:focal(1925x2032:1926x2033)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/eb/72/eb72c673-dfb1-4dd2-bff2-c692226731ae/manatee_1.jpg)

When Kat Nicolaisen, a trainer at Mote Marine Laboratory in Sarasota, Florida, wants Hugh, a 1300-pound manatee, to swim toward her, she holds a white plastic target against the tank wall and the animal glides immediately to it. When she wants Hugh to execute a barrel roll, she carefully traces a circle on its back with her finger and the manatee—covered in short whiskers called vibrissae that conduct tactile sensations—rolls compliantly. When she needs him to lie on his back, she traces a straight line, and the manatee flips over, opening his mouth and waiting patiently for a treat of chopped apples and beets.

You might not guess that the enormous creature was smart or perceptive enough to follow such commands. But manatees are surprisingly intelligent—and once properly motivated, Mote researchers have found, they can perform all sorts of tasks.

This daily training reinforces Hugh's willingness to hold still for a medical examination and participate in behavioral research that guages his hearing and visual acuity. But as recently as a decade ago, all manatees in captivity were routinely sedated or restrained for the simplest of diagnostic tests, and it was unthinkable to consider that they’d be able to follow any sort of instructions.

For manatees and other animals at Mote, a new paradigm of animal research is starting to emerge. Researchers are discovering that some scientific questions can only be answered when they ask animals like Hugh to take part in their research.

"A lot of it is common sense. It's so much easier, in the long run, to work with an animal, rather than fight it and force it to do things," says Joseph Gaspard, who heads Mote's manatee program. "Every other facility for manatees has to drain the tank and restrain them with ten to fifteen people just to treat a little wound or take blood."

And a huge percentage of the animals they keep in captivity, it turns out, are plenty smart enough to undergo this sort of training. "This slow-moving, big-bodied, dim-witted association that people have for manatees is unfortunate," Gaspard adds. "They're very well-evolved for their niche and very intelligent." Using this intelligence—along with that of other species—makes research and caretaking easier, less stressful for the animal and more informative for all parties involved.

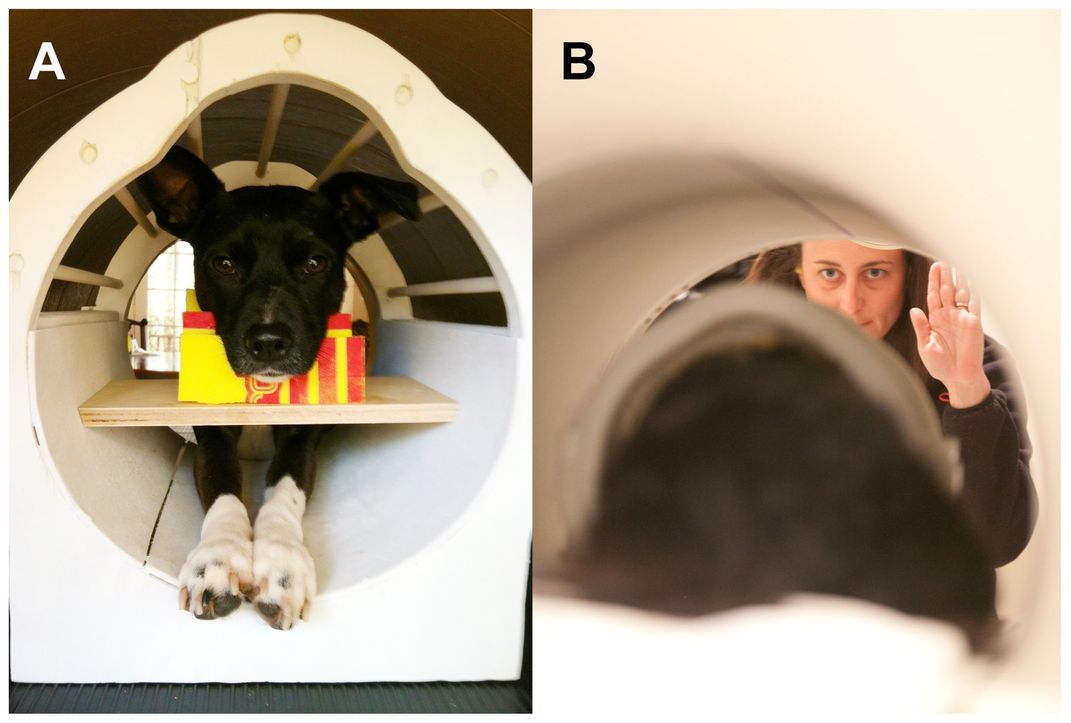

This sort of transition is happening at dozens of research labs, zoos, aquariums and other facilities around the country. At Gregory Berns' lab at Emory University, for instance, dogs have been trained to stay still inside an fMRI machine. Berns and other researchers are interested in learning about dogs' neurological architecture, and sedating or restraining them for imaging studies would ruin the data, yielding an image of a tranquilized or stressed dog's brain, rather than a normal one.

Instead, he and others have recruited dog owners from the community to help them gradually train amenable pets to tolerate the noise and motion of an fMRI machine for up to 30 seconds at a time. As a result, they've produced novel data about the canine brain's reward systems and how they respond to human interactions.

For several decades, in non-research settings like zoos, caretakers have used rewards and operant conditioning to train animals for caretaking purposes. At the Smithsonian National Zoo, for instance, elephants have been trained to stick their feet out of their enclosured to be checked by vets for injuries, lions and other big cats have been trained to hold their mouths open for dental exams and Mei Xiang, the zoo's female panda, is even capable of getting into a squatting position so vets can administer a pelvic exam.

But Mote, which mostly houses injured animals that can't be released into the wild, is one of just a few research facilities using this sort of training towards scientific ends too. Because no one had ever tried to train manatees before, Gaspard says, "we basically had to start from scratch."

He and colleagues figured out that the best way to entice Hugh and the other resident manatee, Buffett, into following instructions was to supplement their vegetable-heavy diet (they each eat about 72 heads of lettuce daily) with rewards of chopped apples, carrots and beets when they did something correctly. The researchers issue these instructions by drawing with their fingers on the manatees' skin, because touch seems to be the creatures' most acute sense.

Elsewhere at the facility, turtles are trained to participate in behavioral tests using the same principles. On one recent day, trainers tested the hearing of resident loggerhead turtles by holding speakers underwater and rewarding the animals with a taste of squid when they swam towards the speaker that emitted a tone. This is part of the first-ever behavioral hearing project on loggerheads, a subject that could eventually help sustain the endangered speices because it could determine whether loud human activities like shoreline dredging could be interfering with their copulation.

But there are other benefits to this one-on-one training work. "We want to see what makes these animals tick," Gaspard says, "so we focus on sensory and physiology." They've measured manatees' extreme sensitivity to touch, for instance, and determined that the animals can poinpoint tactile stimuli on their skin with sub-millimeter resolution.

Like training at zoos, it makes necessary veterinary tasks—taking blood, cleaning wounds, conducting physical exams—much less stressful for the animals. It also gives them something that many animals in captivity sorely lack. "It's a form of stimulation," Gaspard says. "They're thinking, they're getting tested, they're being challenged."

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/joseph-stromberg-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/1a/97/1a9799ad-ec13-41a9-87ea-6749e83c1562/img_7040.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/joseph-stromberg-240.jpg)