I’m scuttling through a shadowy fairyland of stalactites and stalagmites deep within a cave in southern Spain, an experience as daunting as it is exhilarating. Cueva de Ardales is cool, musty and slightly damp, a contrast to the midsummer sun blazing outside. Garbled voices echo in the distance and beams of headlamps flash nervously in the dark, throwing spooky silhouettes on the limestone. In the flickering half-light I listen to water trickling along a runnel cut into the stone floor and search for the ancient markings that remain tucked beneath layers of calcium carbonate like pentimenti in an old painting.

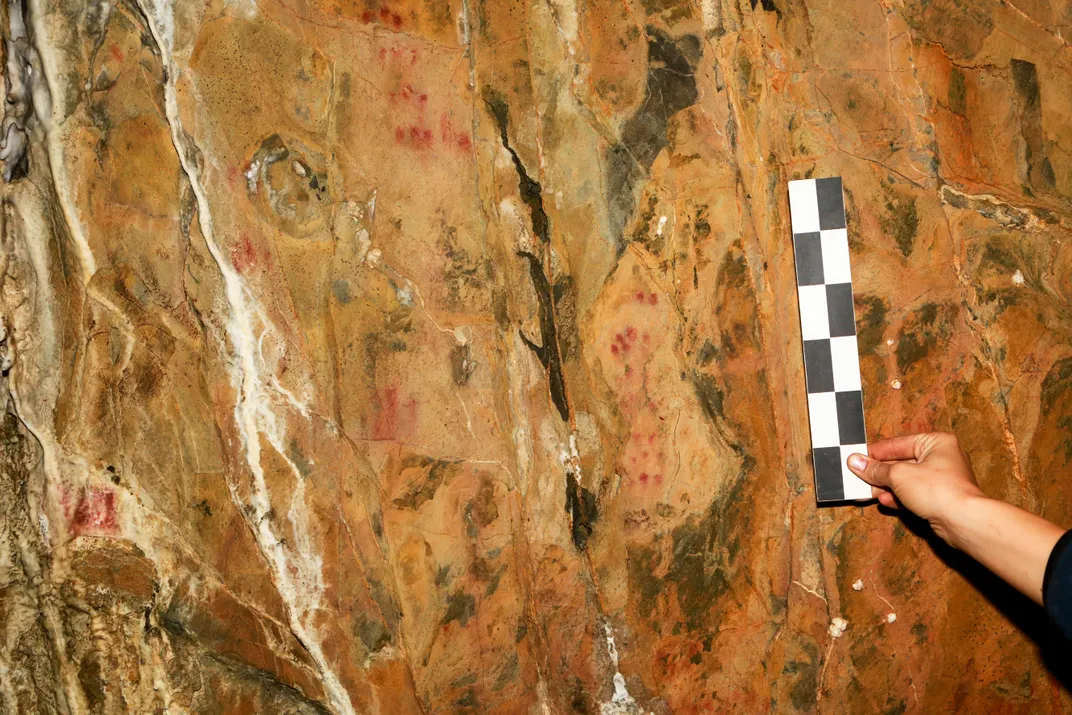

In a corner of the cave, cloaked in shadow, my fellow spelunker, the Portuguese archaeologist João Zilhão, inspects a flowing curtain of stalactites with a laser pointer. As we huddle together, red points of light bounce around the surface, finally settling on a pair of blotches. The designs, hazy circles in red ocher, survive in tattered remnants. Cueva de Ardales is one of three sites in Spain examined by Zilhão and his colleagues. Separated by hundreds of miles, the caves house distinctively splotchy handiwork—vivid patterns (spheres, ladders or hand stencils) have been stippled, splattered or spat on the walls and ceilings.

Wielding drills and surgical scalpels, Zilhão’s international team of researchers grind and scrape the milky crusts of minerals that dripping groundwater has left on top of the blotches. At each sampled spot, a few milligrams of veneer is removed without actually touching the final coat of calcite that overlays the ocher. “The idea is to avoid damaging the paintings,” says expert dater Alistair Pike. The flecks will be sent to a lab at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany, where their minimum age will be evaluated using uranium-thorium dating, a technique relatively new to paleoanthropology that’s more accurate, less destructive and can reach back further in time than traditional methods.

Last year the results of sampling at the three caves were published, and our understanding of prehistoric artistic creation was upended. Analysis showed that some of the markings had been composed no fewer than 64,800 years ago, a whopping 20 millennia before the arrival of our Homo sapiens ancestors, the presumed authors. The implication: The world’s first artists—the Really Old Masters—must have been Neanderthals, those stocky, stooped figures, preternaturally low-browed, who became extinct as sapiens inherited the earth.

“More than a dozen of the paintings have turned out to be the oldest known art in Europe, and, with current knowledge, the oldest in the world,” says Zilhão, a professor at the University of Barcelona.

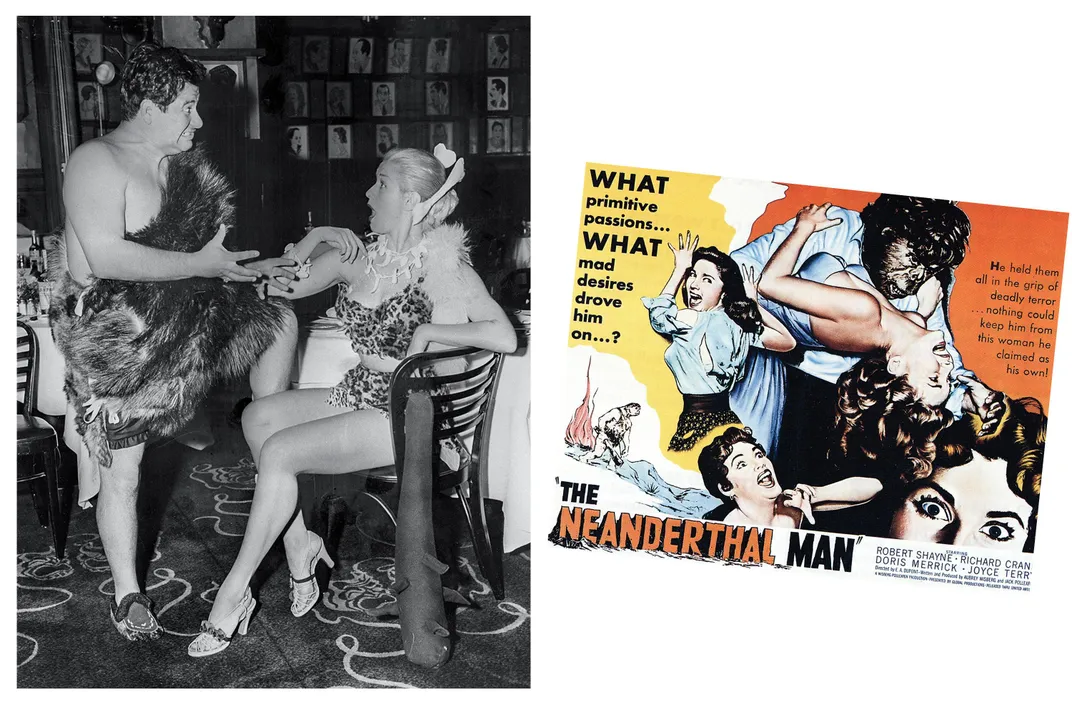

Ever since the summer of 1856, when quarrymen in Germany’s Neander Valley dug up part of a fossilized skull with a receding forehead, researchers have argued about the position of this group of early people in the human family tree. Though they apparently thrived in Europe and Western Asia from about 400,000 to 40,000 B.C., Homo neanderthalensis got a bad rap as lamebrained brutes who huddled in cold caves while gnawing at slabs of slain mammoth. Nature’s down-and-outs were judged to be too dimwitted for moral or theistic conceptions, probably devoid of language and behaviorally inferior to their modern human contemporaries.

A new body of research has emerged that’s transformed our image of Neanderthals. Through advances in archaeology, dating, genetics, biological anthropology and many related disciplines we now know that Neanderthals not only had bigger brains than sapiens, but also walked upright and had a greater lung capacity. These ice age Eurasians were skilled toolmakers and big-game hunters who lived in large social groups, built shelters, traded jewelry, wore clothing, ate plants and cooked them, and made sticky pitch to secure their spear points by heating birch bark. Evidence is mounting that Neanderthals had a complex language and even, given the care with which they buried their dead, some form of spirituality. And as the cave art in Spain demonstrates, these early settlers had the chutzpah to enter an unwelcoming underground environment, using fire to light the way.

The real game-changer came in 2013, when, after a decades-long effort to decode ancient DNA, the Max Planck Institute published the entire Neanderthal genome. It turns out that if you’re of European or Asian descent, up to 4 percent of your DNA was inherited directly from Neanderthals.

No recent archaeological breakthrough has confounded assumptions about our long-gone cousins more than the dating of the rock art in Spain.

The squabbles over the intelligence and taxonomic status of these archaic humans have gotten so bitter and so intense that some researchers refer to them as the Neanderthal Wars. Over the years battle lines have been drawn over everything from the shape of Neanderthals’ noses and the depth of their trachea to the extent to which they interbred with modern humans. In the past, the combatants have been at each other’s throats over authorship of the cave art, which had been hampered by lack of precise dating—often sapiens couldn’t be ruled out as the real artists.

The latest rumpus centers on whether the abstract patterns qualify as symbolic expression, the $64,000 question of 64,800 years ago. “The emergence of symbolic material culture represents a fundamental threshold in the evolution of humankind—it is one of the main pillars of what makes us human,” says geochemist Dirk Hoffmann, a lead author of the cave art study.

Zilhão says the debate over whether the cave art qualifies as symbolic expression “touches deeply on a concern that goes far beyond academic rivalries. It confronts the issue of how special we, as modern humans, actually are, how distinct we are—or are not—from humans who were not quite ‘us.’”

Zilhão has been the Neanderthals’ loudest and most persistent advocate. At 62, he’s more or less the de facto leader of the movement to rehabilitate a vanished people. “The mainstream narrative of our origins has been fairly straightforward,” he says. “The exodus of modern humans from Africa was depicted like it was a biblical event: Chosen Ones replacing debased Europeans, the Neanderthals.

“Nonsense, all of it.”

* * *

Zilhão is a plucked sparrow of a man, thin as a wand, with twin dikes of hair that keep the baldness at bay. At this particular moment he’s wearing what is essentially his uniform: a gray T-shirt, jeans, hiking boots and a scruffily unshaven mien. He’s declaiming from a bench, shaded by jacaranda, on the fringe of a cobbled Lisbon square. This is Zilhão’s hometown, the birthplace of the fado—the mournful and fatalistic mode of song, where sardines are grilled on limestone doorsteps and bedsheets billow in the breeze.

“Was Fred Flintstone a Neanderthal?” asks a visitor from America.

“No, he was a modern human,” says the professor, deadpan. “He drove a car.”

Lifting his eyes, he makes sure that the joke lands. “The most interesting thing about Fred Flintstone’s car was not that he propelled it with his feet or that his toes were not destroyed by the roller wheels. The most interesting thing was that as soon as the car was invented in the cartoon Pleistocene Epoch, it spread fast and was adaptive, like Henry Ford’s Model T.”

Adaptation is key to Zilhão’s take on Neanderthals. He has long maintained that they were the mental equals of sapiens and sophisticated enough to imagine, innovate, absorb influences, reinvent them and incorporate that knowledge into their own culture. “Sure, there were physical differences between Neanderthals and modern humans,” he says. His tone is soft and measured, but there’s a flinty toughness to his words. “But Neanderthals were humans, and in terms of basic things that make us different, there was no difference.”

On one hand Zilhão is a cogent voice of reason; on the other, a pitiless adversary. “João has a forceful personality and he thinks painfully—to many—logically,” says Erik Trinkaus, an authority on Neanderthal and modern human anatomy at Washington University in St. Louis. “He is not always as tactful as he might be, but then being tactful on these issues has not often gotten through.” Gerd-Christian Weniger, former director of the Neanderthal Museum, near Dusseldorf, Germany, regards Zilhão as a supremely erudite rationalist, a man who pushes hard and rests his case on clarity and reason. Others praise Zilhão’s stubborn integrity and his “Confucian sense of fairness”—meaning that he deals with both defenders and opponents in the same way. Some of those opponents dismiss Zilhão as an absolutist when it comes to vindicating Neanderthals.

The eldest child of an engineer father and a psychiatrist mother, Zilhão was inclined to subversiveness from an early age. The Portugal of his youth was a country emaciated by 48 years of dictatorship and five centuries of colonial empire. Young João rejected the constraints of the fascist regimes of António de Oliveira Salazar and Marcello Caetano, and joined the student protests against them. He was a high school senior when Caetano was overthrown in an army coup.

Zilhão was barely a teenager when he started caving in the cliffs overlooking Lisbon. He slid and squeezed through the narrow passages of Galeria da Cisterna, a vast sponge of interconnected shafts, pitches and chasms. It was there, in 1987, when he returned to the site, that he made a major archaeological discovery—7,500-year-old Early Neolithic relics from Portugal’s first farming community. Thirty years of significant Paleolithic discoveries would follow.

In 1989, six years before completing his doctorate in archaeology at the University of Lisbon, Zilhão and a colleague went spelunking in the Galeria. They shimmied up a vertical tunnel and stumbled upon the hidden back entrance to another cave, the Gruta da Oliveira. In a hollow of the cavern were tools, bones and ancient hearths. Dating of artifacts would show that the hideaway was one of the last Neanderthal sanctuaries in Europe.

Zilhão didn’t think much about Neanderthals again until 1996, when he read a paper in Nature about human remains uncovered years before in a cave in central France. Strewn among skeletal fragments in the same layer of dirt were delicately carved bones, ivory rings, and pierced teeth. The research team, led by Jean-Jacques Hublin, proposed that the remains were of Neanderthals and that these objects used for personal ornamentation reflected the acculturation of the Neanderthals by the moderns.

The Upper Paleolithic tools and pendants discovered with the Neanderthal oddments had been found deeper at the site than a deposit with the earliest signs of modern humans. Elsewhere in France, the same types of tools and ornaments were likewise found to predate the earliest evidence for sapiens. Zilhão believes this pattern implied that the Neanderthal layer had formed before moderns had even reached France. Nonetheless, Hublin’s team argued that the bling was created by Neanderthals who must have come into contact with sapiens and were influenced by or traded with them.

That infuriated Zilhão. “Views of the Neanderthals as somehow cognitively handicapped were inconsistent with the empirical evidence,” he says. Zilhão conferred with Francesco d’Errico, a prehistory researcher at the University of Bordeaux. “It seemed obvious to us that Neanderthals had created these things and that therefore archaeologists should revise their thinking and their current models.”

Zilhão and d’Errico met at the Sorbonne in Paris to see the material for themselves. To the surprise of neither, the jewelry didn’t look like knockoffs of what Europe’s earliest modern humans had made, using different kinds of animal teeth and different techniques to work them. “After just a day’s look at the evidence, we realized that neither ‘scavenger’ nor ‘imitation’ worked,” Zilhão says. “You cannot imitate something that does not exist.”

* * *

The gentleman in the charcoal-gray suit is leaning on a railing in the gallery of the Neanderthal Museum. He has a gnarled face and brushed-back hair and scrunched-up eyes that seem to be off on a secret, faraway trip. He looks like Yogi Berra formulating a Yogi-ism or maybe a Neanderthal contemplating fire. Indeed, he is a Neanderthal, albeit a Neanderthal dummy. Which we now know to be an oxymoron.

The museum, which houses a permanent exhibition about the human journey, from our beginnings in Africa four million years ago up to the present, is set at the bottom of a limestone gorge in the Neander Tal (or valley), surely the only place in the world where calling a local a “Neanderthal” is not an unambiguous insult. The building is just a bone’s throw from the spot where workmen found the original Neander Valley fossil fragments buried in four to five feet of clay in 1856.

Cave bear, thought the quarry foreman who salvaged the specimens and took them to Johann Karl Fuhlrott, a schoolteacher and fossil enthusiast. Fuhlrott sent a cast of the cranium to Hermann Schaaffhausen, a professor of anatomy at the University of Bonn. They agreed that the remains were vestiges of a “primitive member of our race” and together announced the finding in 1857. “The discovery was not well received,” Weniger, the museum director, says. “It contradicted literal interpretations of the Bible, which reigned in the days before Darwin’s On the Origin of Species. In scholarly circles, there has been a collective prejudice against Neanderthals. It’s the nature of the profession.”

Unprepared for the notion of a divergent species, most elite scholars disputed the Neanderthal’s antiquity. The anatomist August Mayer speculated that the specimen had been a rickets-afflicted Cossack cavalryman whose regiment had pursued Napoleon in 1814. The man’s bowed bones, he said, were caused by too much time in the saddle. The pathologist Rudolf Virchow blamed the flattened skull on powerful blows from a heavy object. The thick brow-ridges? The result of perpetual frowning. In 1866—seven years after the publication of Darwin’s bombshell book—German biologist Ernst Haeckel proposed calling the species Homo stupidus. The name didn’t stick, but the stigma did. “Unfortunately,” concedes Zilhão, “you never get a second chance to make a first impression.”

The caricature of Neanderthals as shambling simians derives largely from a specimen that achieved a degree of fame, if not infamy, as the Old Man of La Chapelle. In 1911, a time when dozens of Neanderthal bones were excavated in southern France, paleontologist Marcellin Boule reconstructed a nearly complete skeleton, found at La Chapelle-aux-Saints. Burdened by the prevailing preconceptions of Neanderthals, his rendering featured chimplike opposable toes, and a head and hips that jutted forward because the poor fellow’s bent spine kept him from standing upright. To Boule, the Old Man’s crooked posture served as a metaphor for a stunted culture. The shape of the skull, he wrote, indicated “the predominance of functions of a purely vegetative or bestial kind.” It wasn’t until 1957 that the Old Man’s dysmorphia was recognized as the byproduct of several deforming injuries and severe osteoarthritis, a degenerative joint disease. “For Boule, Neanderthals were a side branch of humanity, a dead end in evolution,” says Zilhão. “His crude stereotype went unchallenged until the end of the century.”

By 1996, when Zilhão entered the fray, the question of human emergence had been long dominated by two utterly contradictory schools of thought. No one disputed that the Neanderthals and sapiens descended from a common ancestor in Africa. The ancient bones of contention: Who were the first humans and where did they come from and when?

The first model held that humans belonged to a single species that began migrating from Africa almost two million years ago. Dispersing rapidly, those ancient Africans evolved as more or less isolated groups in many places simultaneously, with populations mating and making cultural exchanges, perhaps as advanced newcomers drifted in and added their DNA to the local gene pool. According to that model, called Multiregional Evolution, the smaller numbers of Neanderthals mated with much larger populations of sapiens. Over time, Neanderthal traits disappeared.

The competing view, Recent African Origin, or the Replacement model, argued that barely 150,000 to 190,000 years ago, many sapiens left the continent of Africa to make their way in the rest of the world, outwitting or supplanting their predecessors (think Neanderthals), without appreciable interbreeding. They brought with them modern behavior—language, symbolism, technology, art.

In the absence of clinching evidence either way, the argument raged merrily on.

Few of the Replacement kingpins reacted in higher dudgeon than Paul Mellars of the University of Cambridge. Convinced of the sapiens’ ascendancy, Mellars declared that Neanderthals were either incapable of art or uninterested in aesthetics. In a confutation oozing with Victorian condescension, he likened the Neanderthals’ cognitive talents to those of colonial-era New Guineans: “No one has ever suggested that the copying of airplane forms in New Guinea cargo cults implied a knowledge of aeronautics or international travel.”

Though Zilhão wasn’t fazed, his recall of the putdown, published more than 20 years earlier, is still vivid. “Many prominent figures in the field are prominent only in the sense that they are the high-priests of a new cult, the Church of the Dumb Neanderthal.”

While under siege, Zilhão met Erik Trinkaus, a fierce advocate of the Assimilation Model, a human origin hypothesis first expressed in the 1980s. The model proposed that Neanderthals and archaic people like them were absorbed through extensive interbreeding.

The meeting with Trinkaus turned out to be serendipitous. During the fall of 1998, Zilhão was told that one of his team had made a strange discovery at the Lagar Velho archaeological site in central Portugal. The researcher had reached into a rabbit hole and pulled out a radius and an ulna—the bones of a human forearm. Zilhão got there expecting to find the fossil of an early modern human. Instead, the remains were of a 4-year-old child who’d been buried in the sediment for nearly 30,000 years. To Zilhão’s infinite amazement, the child had a sapiens’ prominent chin, tooth size and spinal curvature as well as the stout frame, thick bones and short legs of a Neanderthal.

Zilhão called in Trinkaus.

After an examination, Trinkaus surfaced with a radical verdict: the child was a hybrid—and no one-off love child at that. Morphological analysis indicated assimilation took place and there was still evidence of it 1,000 years later. A paper was published in 1999 and a furor followed, as scholars tussled over the implications for human evolution. One proponent of Replacement claimed the body was merely a “chunky child,” a descendant of the sapiens who had wiped out the Neanderthals of the Iberian Peninsula. That critic sneered that the “brave and imaginative interpretation” of Zilhão, Trinkaus and their fellow researchers amounted to “courageous speculations.”

Undeterred, Zilhão and Trinkaus labored on. In 2002, cavers found a human mandible in Pestera cu Oase, a bear cave in the Carpathian Mountains of Romania. Carbon-dating determined the mandible was between 34,000 and 36,000 years old, making it the oldest, directly dated modern human fossil. Like the Lagar Velho child, the find presented a mosaic of early modern human and possible Neanderthal ancestry. Again, a paper was published. Again, the pundits scoffed. But this time Zilhão and Trinkaus got the last laugh. In 2015, DNA analysis showed that the owner of the jawbone had a Neanderthal in his lineage as recently as four generations back.

“These days, you hardly see a genetics paper that is not all about interbreeding,” says Zilhão. “Even so, a redoubt of ‘ardent believers’ in the Replacement theory remains active, especially among archaeologists who prefer to cling to received wisdom or their own long-held views. Human nature, I guess.”

* * *

The glass-and-concrete Max Planck Institute rises amid the Soviet-style housing blocks of old East Germany. This structure sports a rooftop sauna, a grand piano in the lobby and a four-story climbing wall. On the second floor is the office of Jean-Jacques Hublin, director of the Department of Human Evolution. His work is devoted to exploring the differences that make humans unique.

Sitting half in sunlight and half in shadow, Hublin has the thin, weary, seen-it-all sophistication that paleoanthropologists share with homicide detectives, pool sharks and White House correspondents. A longtime Replacement theorist, he’s one of the “ardent believers” Zilhão refers to. Hublin, who’s 65, doesn’t buy into the idea that Neanderthals had the capacity to think abstractly, a capacity that, as Zilhão asserts, was fundamentally similar to our own.

Skeptical by nature and zetetic by training, Hublin was 8 when his family fled French Algeria in the final year of the war for independence. The clan settled in a housing project in the Paris suburbs. “Maybe because of my personal history and childhood, I have a less optimistic view of humans in general,” he says.

Whereas Zilhão is interested in the similarities between sapiens and Neanderthals, Hublin is more interested in the contrasts. “I think somehow differences are more relevant for our understanding of the evolutionary processes. In the end, to prove everyone is like everyone else is maybe morally satisfying, but does not teach us anything about the past.”

He’s especially hard on Zilhão, who he thinks is on a “mission from God” to prove that Neanderthals were the equals of modern humans in every respect. “In other words,” says Hublin, “that Neanderthals did not use iPhones, but only because they lived 60,000 years before Apple was created. If not, they would probably run the company today.”

Read back to Zilhão, that statement makes him chuckle. “I’m pretty sure that Neanderthals would know better than that,” he says. “Smart people do not let themselves be enslaved by Apple.”

Nine years ago Zilhão reported that he had found solid signs that Neanderthals were using mollusk shells in a decorative and symbolic way. Some of the shells found in a Spanish cave were stained with pigment; some were perforated, as if to accommodate a string. Subsequent dating showed them to be 115,000 years old, which ruled out modern humans. Hublin was not swayed. “João thinks he has shells that have been used by Neanderthals in one site in Spain. So where are the other sites where we can find this behavior in Neanderthals? In Africa, there are many sites where we found shells used by sapiens. With Neanderthals there has been just one. To me, that kind of speculation is not science.”

This complaint elicits a brief response from Zilhão. “Not one site, two,” he says.

Hublin is not satisfied that the Cueva de Ardales splotches are even art. “The most pro-Neanderthal people like to reason in terms of present actions or features, which means they would say, ‘We found a handprint, therefore Neanderthals had art.’ This implies that if they had art, they could paint the Mona Lisa. The reality is that using colors to make a mark with your hand or painting your body in red ocher is not like painting a Renaissance picture of the Quattrocento.” Hublin says he won’t be persuaded until he sees a realistic representation of something by a Neanderthal. “Maybe it will happen. I think it’s fine to speculate in your armchair about what could exist, but until it exists, as a scientist, I cannot consider that.”

But must all cave art necessarily be representational? Even 64,800-year-old cave art painted 45,000 years before the Paleolithic bison and aurochs of Lascaux? Jerry Saltz, the Pulitzer Prize-winning art critic, doesn’t think so. “Neanderthals made art, they had a material culture where they traded stones,” he said in a recent City University of New York interview. “They made tools and made them symmetrical—they made them beautiful.” Though the early cave people didn’t sell their finger paintings at Christie’s, Saltz is willing to bet that they traded them for baskets or meat or better flint. “They put value in it. We are God when it comes to art. We place its life force in it.”

* * *

Before injecting himself with a transformative science juice, the doomed professor in the 1950s horror film The Neanderthal Man holds forth to a roomful of doubting naturalists on how much larger the brains of early humans were: “Modern man’s boasting pride in his alleged advancement is based upon one hollow precept, and that is his own ego.” The naturalists jeer and walk out on him.

Alistair Pike’s lab at the University of Southampton in England is not unlike the professor’s. All that’s missing are the beakers and test tubes. It was Pike’s crack team that dated the Spanish cave art and proved it was painted by Neanderthals. Standing beside his trusty accelerator mass spectrometer, he explains how the machine analyzed the mineral crusts found on cave formations, which contained the traces of uranium and thorium that revealed when the deposits formed.

Because the amount of uranium in calcite declines as it decays into thorium, the ratio of those radioactive isotopes is like a clock that starts ticking the moment the crusts form: the higher the ratio of thorium to uranium, the older the calcite. Radiocarbon dating, on the other hand, becomes increasingly unreliable beyond about 40,000 years. Restricted to organic materials like bone and charcoal, carbon dating is unsuitable for drawings made purely with mineral pigments. “There are new technologies that just come along that provide us new opportunities to interrogate the past,” says Pike. “It’s now kind of reaching archaeology.”

He grew up in the village of Norfolk and got into the field at age 6. His mother, an Australian, told him that if he dug a hole deep enough he’d reach the land down under. So he dug and dug and dug. At the bottom of his hole he found the foreleg bones of a horse. “To get the rest out, I started to tunnel,” he says. “When my mum found out I was tunneling, she shut the mine down.”

Pike is an affable guy with enough hair for four people. He’s been collaborating with Zilhão and Dirk Hoffmann of the Max Planck Institute since 2005. Unfortunately, governmental agencies won’t always collaborate with them. Six years ago, they were enlisted by archaeologist Michel Lorblanchet to date a series of red cave blotches in south-central France. Based on stylistic comparisons, Gallic researchers had estimated the art to be from 25,000 to 35,000 years ago, a period seemingly brimming with sapiens. The preliminary results from Pike’s U-Th dating gave a very early minimum age of 74,000 years ago, meaning the premature Matisses likely could have been Neanderthals.

When Pike’s team asked permission to return to the site for verification, the French authorities issued a regulation that banned sampling of calcite for uranium-series dating. Outraged, Zilhão hasn’t set foot in France since. “It seems that most of our critics are French scholars,” muses Pike. “They really don’t like the fact that Neanderthals painted.”

Ever since the findings of their Spanish cave art project appeared, Pike and Zilhão have been pummeled in scientific journals. They have dealt swiftly with each indictment. “It’s quite easy to sell us as people on a mission,” Pike says, “especially in the case of João, who has said some very controversial things in the past.”

* * *

From a bench in the sunny Lisbon square, Zilhão says, “Facts are stubborn. You have to accept them the way they are. Science is not about telling people ‘I told you so,’ it’s about different people coming to the same conclusion. It’s a collective endeavor.”

The scent of pastel de nata, the city’s beloved custard tart, hangs sweetly in the air.

“The mistake you cannot make is to judge the past through the eyes of the present. Judge the past on its own terms.”

You say, That’s very hard—our biases are almost impossible to distinguish.

He says, “You have to be conscious of as many as you can.”

You ask, Is that what your critics are doing?

Zilhão flashes a grin as wide as the Lisbon waterfront. “I like it when they are called critics because, for a long time, I was the critic.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/c5/70/c5706d3a-91e8-42c6-899b-39e09ce4365e/may2019_f08_neanderthal.jpg)