New Research Suggests Dr. Seuss Modeled the Lorax on This Real-Life Monkey

Facial recognition software refreshes the classic book’s message on conservation

Millions of Americans grew up with Dr. Seuss’ Lorax, the gruff orange ball of fluff who doggedly guarded his forest of Truffula trees against the greedy Once-ler. Today, in the journal Nature Ecology & Evolution, scientists unveil a surprising possible inspiration for the stern Seuss stalwart: a mustachioed monkey native to the plains of Central Africa, where the author once vacationed.

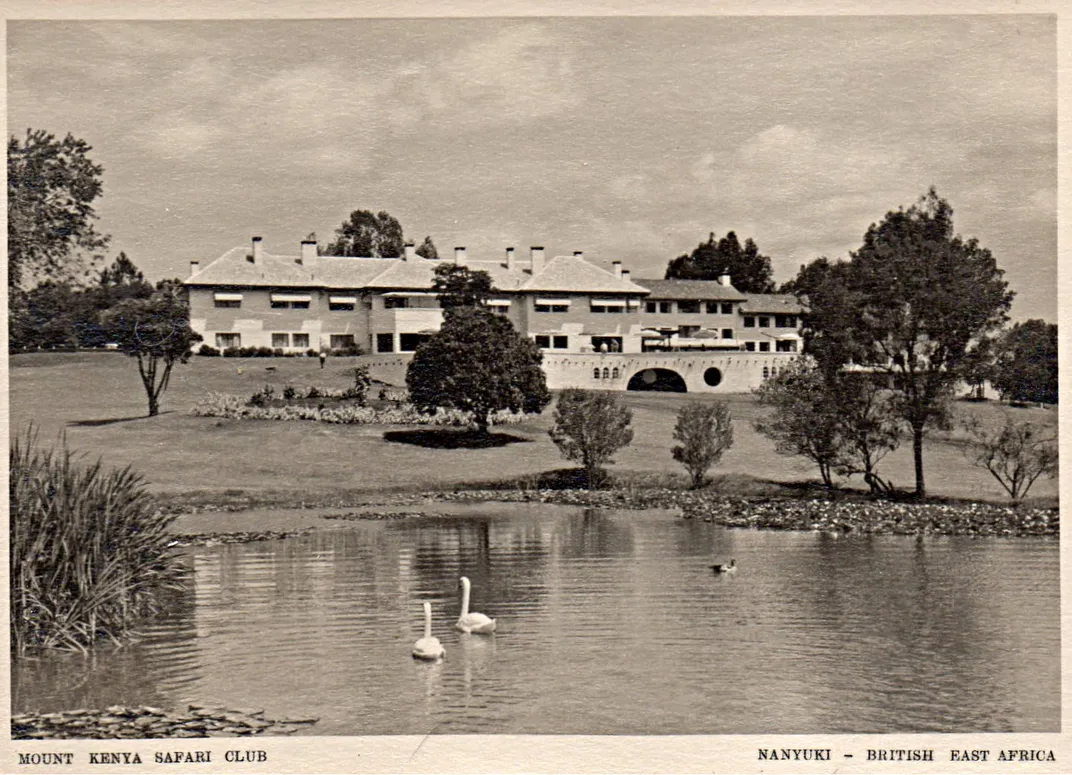

The adventure began in September of 1970 at a celebrity jet setter’s retreat in a lavish Kenyan country club. Owned by actor William Holden, the Mount Kenya Safari Club frequently played host to Hollywood A-listers luxuriating in exclusive cocktail hours and spontaneous safaris. Among them was none other than Theodor Geisel—better known to most as the American author Dr. Seuss.

It was at the Safari Club where, on a late summer afternoon, Seuss composed most of the manuscript that would become The Lorax. The illustrated children’s book, which first hit bookshelves in 1971, is among Seuss’ most famous works and perhaps his most controversial, evoking ire with ecopolitical messaging wrapped in the guise of whimsical rhymes and Seussian charisma.

The fable pits capitalism against biodiversity. It’s a sobering tale of the avaricious Once-ler, who, seduced by wealth, fells yarn-producing Truffula trees to knit lucrative Thneeds. As the forests and wildlife crumble and disappear, the Lorax, who “speaks for the trees,” pleads for the preservation of his ecosystem.

Ultimately, the Lorax’s admonitions fall on deaf ears, and the book ends with Truffulas, and the ecosystem they once supported, on the brink of extinction. But hope glimmers faintly in the book’s final passages: the young narrator takes possession of the last remaining Truffula seed from the now-remorseful Once-ler, who closes with a mournful exhortation:

Unless someone like you

Cares a whole awful lot,

Nothing is going to get better.

It’s not.

Published just as global environmental awareness was beginning to unfurl its wings in the early 1970s, The Lorax is still pointed to as a foundational ecopolitical text. “It really set the tone for how environmental messages should be done,” says lead author Nathaniel Dominy, a professor of anthropology and primate biology at Dartmouth University.

Today, the legacy of the The Lorax lives on, brought into sharply renewed perspective by the growing consequences of human intervention on global biodiversity. But the Lorax himself—in spite of, or perhaps because of, his moral high ground—is not without his critics. Introduced by Seuss as “sharpish and bossy,” the Lorax has even been characterized as an off-putting pedant for his dogmatic demeanor and possessive protests of the damage done to “his” Truffula habitat. For some, the Lorax comes across, according to Dominy, as a “self-appointed eco-policeman”—perhaps no better than the greedy Once-ler he chastises.

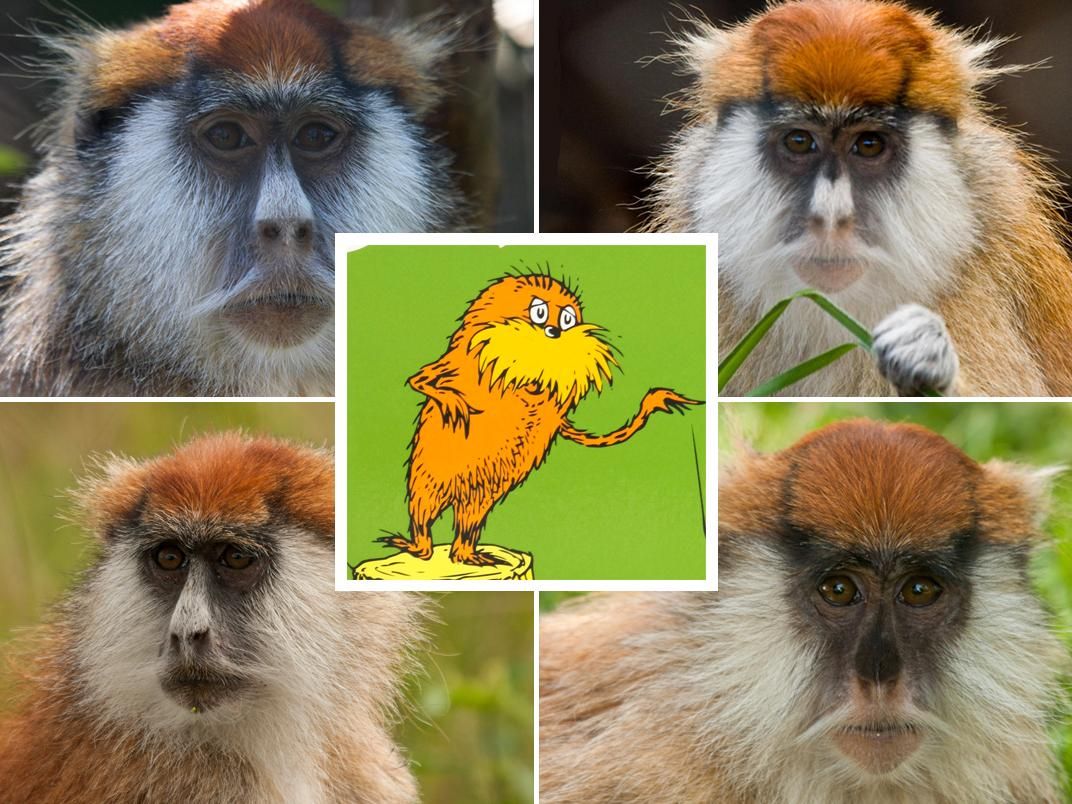

This didn’t fit Dominy’s portrait of Seuss or his work. And so, he foraged for another connection: perhaps the origins of the story had some basis in fact. In the past, Dominy had joked to colleagues about how, if Seuss were to create a primate, “it would turn out something like the patas monkey.” Little did Dominy know at the time, Seuss and his wife had traveled smack into the middle of patas monkey country.

Only months before his fateful trip to Kenya, Seuss had joined a campaign to save the eucalyptus trees being culled from the neighborhood surrounding his home in La Jolla, California. According to study co-author Donald Pease, a professor of American literature and well-known Seuss biographer at Dartmouth, conservation was already at the forefront of Seuss’ mind—but he had been struggling to come up with a story that would resonate with children.

“He felt all of his previous efforts to write a work that would support the so-called environmental protection movement would sound preachy,” Pease explains. “It wasn’t until [his wife] Audrey suggested they go on vacation to Kenya that the story came to him.”

To Dominy’s delight, timing wasn’t the only evidence that supported his theory. With its dark mouth, hooded eyes, and wispy Confucian whiskers, the patas monkey sports an almost comically crotchety countenance not unlike that of the Lorax. Even the “sawdusty sneeze” of the Lorax might have been a quirky reinterpretation of the patas monkey’s wheezy whoop.

There was more. Patas monkeys, it turns out, rely heavily on a certain species of spiked, spindly African tree called the whistling thorn acacia. Only where these trees thrive will patas monkeys be found. The tree’s gum, thorns, flowers and seeds are believed to make up around 80 percent of the monkey’s diet.

“It’s a tree Dr. Seuss could not have missed when he was wandering through the Safari Club,” says Pease. Though patas monkeys are terrestrial, spending much of their time clambering through the reedy savannah grasses, they never stray far from their acacias.

But corroboration of the patas monkey connection is difficult. Seuss died in 1991. And Audrey Geisel, his widow, had an understandably foggy recollection of the vacation the couple had embarked on nearly half a century ago. To complicate matters further, no photos from the fateful trip survived.

Even Pease was skeptical of Dominy’s theory at first: “Seuss took great pride in the inventiveness he associated with the creation of the figures he put in his books,” he explains.

Dominy decided to do some computational sleuthing. He enlisted the help of a former collaborator, senior author James Higham, another primate biologist who frequently utilized computer programming in his research at New York University. Together with study co-author Sandra Winters, a PhD student in Higham’s research group, Dominy and Higham devised a clever protocol to test the relationship between fact and fiction.

Using facial recognition software, they constructed a monkey “face space”: a multidimensional map of faces of primates common to Kenya. Each face represented the average features of a particular species of monkey, with the distance between faces representing the extent of facial similarity. Higham had previously employed this method to uncover new information about the rapid evolution of guenons, the genus of Central African primates that includes patas monkeys.

When Winters and Higham plotted a composite of the Lorax into their monkey face space, he fell in neatly with real monkeys. Even when the researchers included another Seuss character from the earlier The Foot Book, the Lorax resembled a blue monkey or patas monkey more than his Seussian relative. Dominy is fairly certain that Seuss never came into contact with blue monkeys, which inhabit a different sector of the African landscape, during his travels. But patas monkeys and their acacias flourish on the dry plains of the Laikipia plateau in Kenya.

Face spaces are not used as frequently for most of modern facial recognition software, which now focuses primarily on identifying individuals (think of automatic tagging on Facebook) rather than categorizing species. However, according to Alice O’Toole, a professor who studies facial recognition at the University of Texas at Dallas and was not affiliated with the study, it remains a powerful method for this type of work. “I thought it was a clever and innovative use of these older methods,” O’Toole says.

“I always thought the Lorax looked like a guenon, with their little mustaches,” adds Meredith Bastian, curator of primates at the Smithsonian’s National Zoo, who also did not contribute to the study. “It makes a lot of sense to me.”

Whether or not the patas monkey and its acacia tree were what truly cajoled Seuss out of his writer’s block, the mere possibility suggests a more altruistic interpretation of the story. The Lorax’s protectiveness of his Truffula trees—which, like the whistling thorn acacias for patas monkeys, make the difference between life and death. The Lorax may not view his relationship with the forest as proprietary after all; rather, he “speaks for the trees” simply because they cannot speak for themselves. The Lorax and the Truffula trees are, in a sense, one and the same, a single codependent entity on the brink of extinction. “Viewed that way, his self-righteous indignation is more forgivable and understandable,” says Dominy.

“This is the deep message of the Lorax: He is a part of the ecological system, not apart from it,” adds Pease. He explains that this resonates deeply for the human place in the natural world as well: "It undermines the assumption of human exceptionalism—that humans are sequestered from the rest of the natural world in order to benefit from it. If human beings persist in this attitude, the human species itself will be threatened with extinction. It’s only when we acknowledge the fact that we’re part of the environment that we can begin to discover what needs to change.”

“[The study] is a very thorough look at the origin of the Lorax,” says Philip Nel, a professor of children’s literature at Kansas State University, who did not participate in the research. “It provides a much fuller context than has been provided before in any one place.”

Dominy and Pease emphasize that they aren’t championing any sort of revisionist history: they are enriching—not displacing—a familiar discussion. And leveraging the legacy of Lorax lore can be incredibly powerful: what Nel calls a “cultural shorthand” for the environment.

In 2012, the Philadelphia Zoo debuted the Trail of the Lorax, featuring an urgent message to patrons to engage with orangutan conservation. Due to poaching, habitat fragmentation and the encroachment of palm oil plantations, orangutan populations have plummeted in recent decades, leaving all species critically endangered. Noting the parallels between The Lorax and the plight of these apes, the Zoo linked the cultural icon to the real-world stakes of saving lives. Their interactive exhibition encouraged visitors to support companies committed to using sustainable palm oil and spread awareness of continued conservation efforts.

“It’s hard when the animal is halfway around the world. It’s not something people feel they have any control over here in the U.S.,” says Kimberly Lengel, vice president of conservation and education at the Philadelphia Zoo. “[With the Lorax], we made that connection for them and showed people they can have an impact.”

As of yet, patas monkeys are not in similarly dire straits: Their numbers remain relatively high across the plains of Central Africa. However, recent climate change-driven increases in temperature and aridity in Kenya has increased the browsing of elephants, rhinoceroses and giraffes on whistling thorn acacia. Additionally, these trees have been increasingly harvested for their ability to produce high-quality charcoal for nearby human populations. Both these human-driven changes have begun to deplete the patas monkeys’ most important resource.

According to Lynne Isbell, a primate biologist at the University of California at Davis who was not affiliated with the study, the continued loss of the whistling thorn acacia from Laikipia, where Seuss may have first imagined his Lorax, would destroy the “last stronghold” for patas monkeys in Kenya. “It would be an absolute disaster for them,” Isbell says. If these trends continue, patas monkeys could someday be headed for the same fate as the Lorax—and if and when this occurs, who came first will be a moot point.

Of course, Seuss was no oracle. It’s unlikely he was deliberately forecasting the demise of the patas monkey, orangutan or any other specific creature. Inspired by a monkey or not, the Lorax is, ultimately, not real. But his message very much is. For Seuss, it could simply have been that, with the humbling landscape of the African savannah before him, the words finally began to flow.

Maybe, at the end of the day, it hardly matters how much of The Lorax was prophetic fact or fiction. What matters is that an orthodox interpretation has been reinvigorated with a fresh perspective—and, as a result, the conversation on conservation can been reawakened. The Lorax’s potential connection to the patas monkey breathes new life into a work nearing its 50th anniversary as a cornerstone of the ongoing debate on ecopolitics, buoying the hope that, with modern technology and increased awareness, the world’s remaining ecological gems stand a fighting chance.

For a new generation of readers, and the many more still to come, the message of The Lorax lives on—a sign that someone out there still cares “a whole awful lot.” And maybe, just maybe, there’s a chance that things are “going to get better.” Seuss himself couldn’t have asked for more.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/10172852_10152012979290896_320129237_n.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/10172852_10152012979290896_320129237_n.jpg)