This is a love story.

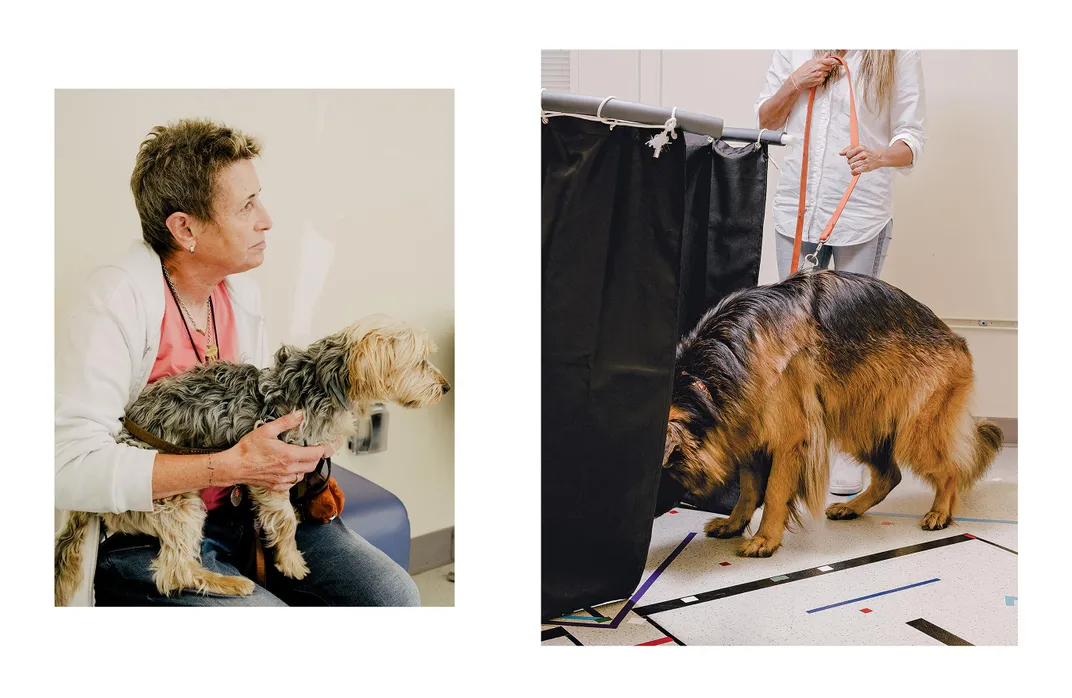

First, though, Winston is too big. The laboratory drapery can conceal his long beautiful face or his long beautiful tail, but not both. The researchers need to keep him from seeing something they don’t want him to see until they’re ready for him to see it. So during today’s brief study Winston’s tail will from time to time fly like a wagging pennant from behind a miniature theater curtain. Winston is a longhaired German shepherd.

This room at the lab is small and quiet and clean, medium-bright with ribs of sunlight on the blinds and a low, blue overhead fluorescence. Winston’s guardian is in here with him, as always, as is the three-person team of scientists. They’ll perform a short scene—a kind of behavioral psychology kabuki—then ask Winston to make a decision. A choice. Simple: either/or. In another room, more researchers watch it all play out on a video feed.

In a minute or two, Winston will choose.

And in that moment will be a million years of memory and history, biology and psychology and ten thousand generations of evolution—his and yours and mine—of countless nights in the forest inching closer to the firelight, of competition and cooperation and eventual companionship, of devotion and loyalty and affection.

It turns out studying dogs to find out how they learn can teach you and me what it means to be human.

It’s late summer at Yale University. The laboratory occupies a pleasant white cottage on a leafy New Haven street a few steps down Science Hill from the divinity school.

I’m here to meet Laurie Santos, director of the Comparative Cognition Laboratory and the Canine Cognition Center. Santos, who radiates the kind of energy you’d expect from one of her students, is a psychologist and one of the nation’s preeminent experts on human cognition and the evolutionary processes that inform it. She received undergraduate degrees in biology and psychology and a PhD in psychology, all from Harvard. She is a TED Talks star and a media sensation for teaching the most popular course in the history of Yale, “Psychology and the Good Life,” which most folks around here refer to as the Happiness Class (and which became “The Happiness Lab” podcast). Her interest in psychology goes back to her girlhood in New Bedford, Massachusetts. She was curious about curiosity, and the nature of why we are who we are. She started out studying primates, and found that by studying them she could learn about us. Up to a point.

“My entry into the dog work came not from necessarily being interested in dogs per se, but in theoretical questions that came out of the primate work.” She recalls thinking of primates, “If anybody’s going to share humanlike cognition, it’s going to be them.”

But it wasn’t. Not really. We’re related, sure, but those primates haven’t spent much time interacting with us. Dogs are different. “Here’s this species that really is motivated to pay attention to what humans are doing. They really are clued in, and they really seem to have this communicative bond with us.” Over time, it occurred to her that understanding dogs, because they are not only profoundly attuned to but also shaped by people over thousands of years, would open a window on the workings of the human mind, specifically “the role that experience plays in human cognition.”

So we’re not really here to find out what dogs know, but how dogs know. Not what they think, but how they think. And more important, how that knowing and thinking reflect back on us. In fact, many studies of canine cognition here and around the academic world mimic or began as child development studies.

Understand, these studies are entirely behavioral. It’s problem-solving. Puzzle play. Selection-making. Either/or. No electrodes, no scans, no scanners. Nothing invasive. Pavlov? Doesn’t ring a bell.

* * *

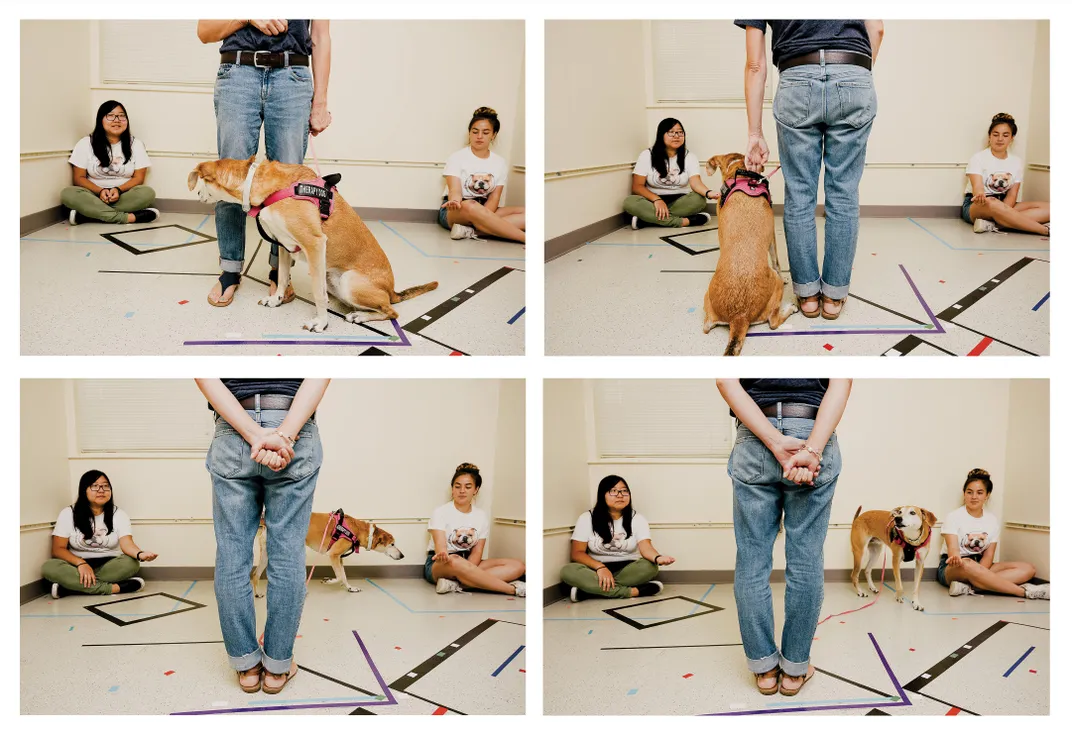

Zach Silver is a PhD student in the Yale lab; we’re watching his study today with Winston. Leashed and held by his owner, Winston will be shown several repetitions of a scene performed in silence by two of the researchers. Having watched them interact, Winston will then be set loose. Which of the researchers he “chooses”—that is, walks to first—will be recorded. And over hundreds of iterations of the same scene shown to different dogs, patterns of behavior and preference will begin to emerge. Both researchers carry dog treats to reward Winston for whichever choice he makes—because you incentivize dogs the same way you incentivize sportswriters or local politicians, with free food, but the dogs require much smaller portions.

In some studies the researchers/actors might play out brief demonstrations of cooperation and non-cooperation, or dominance and submission. Imagine a dog is given a choice between someone who shares and someone who doesn’t. Between a helper and a hinderer. The experiment leader requests a clipboard. The helper hands it over cheerfully. The hinderer refuses. Having watched a scene in which one researcher shares a resource and another does not, who will the dog choose?

The question is tangled up with our own human prejudices and preconceptions, and it’s never quite as simple as it looks. Helping, Silver says, is very social behavior, which we tend to think dogs should value. “When you think about dogs’ evolutionary history, being able to seek out who is prosocial, helpful, that could have been very important, essential for survival.” On the other hand, a dog might choose for “selfishness” or for “dominance” or for “aggression” in a way that makes sense to him without the complicating lens of a human moral imperative. “There could be some value to [the dog] affiliating with someone who is stockpiling resources, holding onto things, maybe not sharing. If you’re in that person’s camp, maybe there’s just more to go around.” Or in certain confrontational scenarios, a dog may read dominance in a researcher merely being deferred to by another researcher. Or a dog may just choose the fastest route to the most food.

What Silver is trying to tease out with today’s experiment is the most elusive thing of all: intention.

“I think intention may play a large role in dogs’ evaluation of others’ behavior,” says Silver. “We may be learning more about how the dog mind works or how the nonhuman mind works broadly. That’s one of the really exciting places we are moving in this field, is to understand the small cognitive building blocks that might contribute to valuations. My work in particular is focused on seeing if domestic dogs share some of these abilities with us.”

As promising as the field is, in some ways it seems that dog nature, like human nature, is infinitely complex. Months later, in a scientific paper, Silver and others will point out that “humans evaluate other agents’ behavior on a variety of different dimensions, including morally, from a very early age” and that “given the ubiquity of dog-human social interactions, it is possible that dogs display humanlike social evaluation tendencies.” Turns out that a dog’s experience seems important. “Trained agility dogs approached a prosocial actor significantly more often than an antisocial actor, while untrained pet dogs showed no preference for either actor,” the researchers found. “These differences across dogs with different training histories suggest that while dogs may demonstrate preferences for prosocial others in some contexts, their social evaluation abilities are less flexible and less robust compared to those of humans.”

Santos explained, “Zach’s work is beginning to give us some insight into the fact that dogs can categorize human actions, but they require certain kinds of training to do so. His work raises some new questions about how experience shapes canine cognition.”

It’s important to create experiments measuring the dog’s actual behaviors rather than our philosophical or social expectation of those behaviors. Some of the studies are much simpler, and don’t try to tease out how dogs perceive the world and make decisions to move through it. Rather than trying to figure out if a dog knows right from wrong, these puzzles ask whether the dog knows right from left.

An example of which might be showing the subject dog two cups. The cup with the treat is positioned to her left, near the door. Do this three times. Now, reversing her position in the room, set her loose. Does she head for the cup near the door, now on her right? Or does she go left again? Does she orient things in the world based on landmarks? Or based on her own location in the world? It’s a simple experimental premise measuring a complex thing: spatial functioning.

In tests like these, you’ll often see the dog look back at her owner, or guardian, for a tip, a hint, a clue. Which is why the guardians are all made to wear very dark sunglasses and told to keep still.

In some cases, the dog fails to make any choice at all. Which is disappointing to the researchers, but seems to have no impact on the dog—who will still be hugged and praised and tummy-rubbed on the way out the door.

Every dog and every guardian here is a volunteer. They come from New Haven or drive in from nearby Connecticut towns for an appointment at roughly 45-minute intervals. They sign up on the lab’s website. Some dogs and guardians return again and again because they enjoy it so much.

It’s confusing to see the sign-up sheet without knowing the dog names from the people names.

Winston’s owner, human Millie, says, “The minute I say ‘We’re going to Yale,’ Winston perks up and we’re in the car. He loves it and they’re so good to him; he gets all the attention.”

And dog Millie’s owner, Margo, says, “At one point at the end they came up with this parchment. You open it up and it says that she’s been inducted into Scruff and Bones, with all the rights and privileges thereof.”

The dogs are awarded fancy Yale dogtorates and are treated like psych department superstars. Which they are. Without them, this relatively new field of study couldn’t exist.

All the results of which will eventually be synthesized, not only by Santos, but by researchers the world over into a more complete map of human consciousness, and a better, more comprehensive Theory of Mind. I asked Santos about that, and any big breakthrough moments she’s experienced so far. “Our closest primary relatives—primates—are not closest to us in terms of how we use social information. It might be dogs,” she says. “Dogs are paying attention to humans.”

Santos also thinks about the potential applications of canine cognition research. “More and more, we need to figure out how to train dogs to do certain kinds of things,” she says. “There are dogs in the military, these are service dogs. As our boomers are getting older, we’re going to be faced with more and more folks who have disabilities, who have loneliness, and so on. Understanding how dogs think can help us do that kind of training.”

In that sense, dogs may come to play an even larger role in our daily lives. Americans spent nearly $100 billion on their pets in 2019, maybe half of which was spent on dogs. The rest was embezzled, then gambled away—by cats.

* * *

From cave painting to The Odyssey to The Call of the Wild, the dog is inescapable in human art and culture. Anubis or Argos, Bau or Xolotl, Rin Tin Tin or Marmaduke, from the religious to the secular, Cerberus to Snoopy, from the Egyptians and the Sumerians and the Aztecs to the canine stunt coordinators of Hollywood, the dog is everywhere with us, in us and around us. As a symbol of courage or loyalty, as metaphor and avatar, as a bad dog, mad dog, “release the hounds” evil, or as a screenwriter’s shorthand for goodness, the dog is tightly woven into our stories.

Maybe the most interesting recent change, to take the movie dog as an example, is the metaphysical upgrade from Old Yeller to A Dog’s Purpose and its sequel, A Dog’s Journey. In the first case, the hero dog sacrifices himself for the family, and ascends to his rest, replaced on the family ranch by a pup he sired. In the latter two, the same dog soul returns and returns and returns, voiced by actor Josh Gad, reincarnating and accounting his lives until he reunites with his original owner. Sort of a Western spin on karma and the effort to perfect an everlasting self.

But even that kind of cultural shift pales compared with the dog’s journey in the real world. Until about a century ago, in a more agrarian time, the average dog was a fixture of the American barnyard. An affectionate and devoted farmhand, sure, herder of sheep, hunting partner or badger hound, keeper of the night watch, but not much different from a cow, a horse or a mule in terms of its utility and its relationship to the family.

By the middle of the 20th century, as we urbanized and suburbanized, the dog moved too—from the back forty to the backyard.

Then, in the 1960s, the great leap—from the doghouse onto the bedspread, thanks to flea collars. With reliable pest control, the dog moves into the house. Your dog is no longer an outdoor adjunct to the family, but a full member in good standing.

There was a book on the table in the waiting room at Yale. The Genius of Dogs, by Brian Hare and Vanessa Woods. Yiyun Huang, the lab manager of the Canine Cognition Center at the time, handed it to me. “You should read this,” she said.

So I did.

Then I flew to Duke University in Durham, North Carolina.

* * *

Not long after I stepped off the plane I walked straight into a room full of puppies.

The Duke Canine Cognition Center is the brain-child of an evolutionary anthropologist named Brian Hare. His CV runs from Harvard to the Max Planck Institute and back. He is a global leader in the study of dogs and their relationships to us and to each other and to the world around them. He started years ago by studying his own dog in the family garage. Now he’s a regular on best-seller lists.

Like Santos, he’s most interested in the ways dogs inform us about ourselves. “Nobody understands why we’re working with dogs to understand human nature—until we start talking about it,” he says. “Laugh if you want, but dogs are everywhere humans are, and they’re absolutely killing it evolutionarily. I love wolves, but the truth is they’re really in trouble”—as our lethal antipathy to them bears out. “So whatever evolutionarily led to dogs, and I think we have a good idea of that, boy, they made a good decision.”

Ultimately, Hare says, what he’s studying is trust. How is it that dogs form a bond with a new person? How do social creatures form bonds with one another? Developmental disorders in people may be related to problems in forming bonds—so, from a scientific perspective, dogs can be a model of social bonding.

Hare works with research scientist Vanessa Woods, also his wife and co-author. It was their idea to start a puppy kindergarten here. The golden and Labrador retriever-mix puppies are all 10 weeks old or so when they arrive, and will be studied at the same time they’re training to become service dogs for the nonprofit partner Canine Companions for Independence. The whole thing is part of a National Institutes of Health study: Better understanding of canine cognition means better training for service dogs.

Because dogs are so smart—and so trainable— there’s a whole range of assistance services they can be taught. There are dogs who help people with autism, Woods tells me. “Dogs for PTSD, because they can go in and spot-check a room. They can turn the lights on. They can, if someone’s having really bad nightmares, embrace them so just to ground them. They can detect low blood sugar, alert for seizures, become hearing dogs so they can alert their owner if someone’s at the door, or if the telephone’s ringing.”

Canines demonstrate a remarkable versatility. “A whole range of incredibly flexible, cognitive tasks,” she says, “that these dogs do that you just can’t get a machine to do. You can get a machine to answer your phone—but you can’t get a machine to answer your phone, go do your laundry, hand you your credit card, and find your keys when you don’t know where they are.” Woods and I are on the way out of the main puppy office downstairs, where the staff and student volunteers gather to relax and rub puppy tummies between studies.

It was in their book that I first encountered the idea that, over thousands of years, evolution selected and sharpened in dogs the traits most likely to succeed in harmony with humans. Wild canids that were affable, nonaggressive, less threatening were able to draw nearer to human communities. They thrived on scraps, on what we threw away. Those dogs were ever so slightly more successful at survival and reproduction. They had access to better, more reliable food and shelter. They survived better with us than without us. We helped each other hunt and move from place to place in search of resources. Kept each other warm. Eventually it becomes a reciprocity not only of efficiency, but of cooperation, even affection. Given enough time, and the right species, evolution selects for what we might call goodness. This is the premise of Hare and Woods’ new book, Survival of the Friendliest.

If that strikes you as too philosophical, over-romantic and scientifically spongy, there’s biochemistry at work here too. Woods explained it while we took some puppies for a walk around the pond just down the hill from the lab. “So, did you see that study that dogs hijack the oxytocin loop?”

I admitted I had not.

Oxytocin is a hormone produced in the hypothalamus and released by the pituitary gland. It plays an important role in human bonding and social interaction, and makes us feel good about everything from empathy to orgasm. It is sometimes referred to as the “love hormone.”

Woods starts me out with the underpinnings of these kinds of studies—on human infants. “Human babies are so helpless,” she says. “You leave them alone for ten minutes and they can literally die. They keep you up all night, they take a lot of energy and resources. And so, how are they going to sort of convince you to take care of them?”

What infants can do, she says, “is they can look at you.”

And so this starts an oxytocin loop where the baby looks at you and your oxytocin goes up, and you look at the baby and the baby’s oxytocin goes up. One of the things oxytocin does is elicit caregiving toward someone you see as part of your group.

Dogs, it turns out, have hijacked that process as well. “When a dog is looking at me,” Woods says, “his oxytocin is going up and my oxytocin is going up.” Have you ever had a moment, she asks, when your dog looks at you, and you just don’t know what the dog wants? The dog has already been for a walk, has already been fed.

“Sure,” I responded.

“It’s just kind of like they’re trying to hug you with their eyes,” she says.

Canine eyebrow muscles, it turns out, may have evolved to reveal more of the sclera, the whites of the eyes. Humans share this trait. “Our great ape relatives hide their eyes,” Woods says. “They don’t want you to know where they’re looking, because they have a lot more competition. But humans evolved to be superfriendly, and the sclera is part of that.”

So, it’s eye muscles and hormones, not just sentiment.

In the lab here at Duke, I see puppies and researchers work through a series of training and problem-solving scenarios. For example, the puppy is shown a treat from across the room, but must remain stationary until called forward by the researcher.

“Puppy look. Puppy look.”

Puppy looks.

“Puppy stay.”

Puppy stays.

“Puppy fetch.”

Puppy wobbles forward on giant paws to politely nip the tiny treat and to be effusively praised and petted. Good puppy!

The problem-solving begins when a plexiglass shield is placed between the puppy and the treat.

“Puppy look.”

Puppy does so.

“Puppy fetch.”

Puppy wobbles forward, bonks snout on plexiglass. Puppy, vexed, tries again. How fast the puppy susses out a new route to the food is a good indication of patience and diligence and capacity for learning. Over time the plexiglass shields become more complicated and the puppies need to formulate more complex routes and solutions. As a practical matter, the sooner you can find out which of these candidate puppies is the best learner, the most adaptive, the best suited to the training—and which is not—the better. Early study of these dogs is a breakthrough efficiency in training.

I asked Hare where all this leads. “I’m very excited about this area of how we view animals informs how we view each other. Can we harness that? Very, very positive. We’re working already on ideas for interventions and experiments.”

Second, Hare says, much of their work has focused on “how to raise dogs.” He adds, “I could replace dogs with kids.” Thus the implications are global: study puppies, advance your understanding of how to nurture and raise children.

“There’s nice evidence that we can immunize ourselves from some of the worst of our human nature,” Hare recently told the American Psychological Association in an interview, “and it’s similar to how we make sure that dogs are not aggressive to one another: We socialize them. We want puppies to see the world, experience different dogs and different situations. By doing that for them when they’re young, they aren’t threatened by those things. Similarly, there is good evidence that you can immunize people from dehumanizing other groups just through contact between those groups, as long as that contact results in friendship.”

Evolutionary processes buzz and sputter all around us every moment. Selection never sleeps. In fact, Hare contributed to a new paper released this year on how rapidly coyote populations adapt to humans in urban and suburban settings. “How animal populations adapt to human-modified landscapes is central to understanding modern behavioural evolution and improving wildlife management. Coyotes (Canis latrans) have adapted to human activities and thrive in both rural and urban areas. Bolder coyotes showing reduced fear of humans and their artefacts may have an advantage in urban environments.”

The struggle between the natural world and the made world is everywhere constant, and not all possible outcomes lead to friendship. Just ask those endangered wolves—if you can find one.

The history of which perhaps seems distant from the babies and the students and these puppies. But to volunteer for this program is to make a decision for extra-credit joy. This is evident toward the end of my day in Durham. Out on the lab’s playground where the students, puppy and undergraduate alike, roll and wrestle and woof and slobber under that Carolina blue sky.

* * *

In rainy New York City, I spent an afternoon with Alexandra Horowitz, founder and director of the Horowitz Dog Cognition Lab at Barnard College, and the best-selling author of books including Being a Dog, Inside of a Dog, and Our Dogs, Ourselves. She holds a doctorate in cognitive science, and is one of the pioneers of canine studies.

It is her belief that we started studying dogs only after all these years because they’ve been studying us.

She acknowledges that other researchers in the field have their own point of view. “The big theme is, What do dogs tell us about ourselves?” Horowitz says. “I am a little less interested in that.” She is more interested in the counter question: What do cognition studies tell us about dogs?

Say you get a dog, Horowitz suggests. “And a week into living with a dog, you’re saying ‘He knows this.’ Or ‘She is holding a grudge’ or, ‘He likes this.’ We just barely met him, but we’re saying things that we already know about him—where we wouldn’t about the squirrel outside.”

Horowitz has investigated what prompts us to make such attributions. For instance, she led a much-publicized 2009 study of the “guilty look.”

“Anthropomorphisms are regularly used by owners in describing their dogs,” Horowitz and co-authors write. “Of interest is whether attributions of understanding and emotions to dogs are sound, or are unwarranted applications of human psychological terms to nonhumans. One attribution commonly made to dogs is that the ‘guilty look’ shows that dogs feel guilt at doing a disallowed action.” In the study, the researchers observed and video-recorded a series of 14 dogs interacting with their guardians in the lab. Put a treat in a room. Tell the dog not to eat it. The owner leaves the room. Dog eats treat. Owner returns. Does the dog have a “guilty look”? Sometimes yes, sometimes no, but the outcome, it turns out, was generally related to the owner’s reaction—whether the dog was scolded, for instance. Conclusion: “These results indicate that a better description of the so-called guilty look is that it is a response to owner cues, rather than that it shows an appreciation of a misdeed.”

She has also focused on a real gap in the field, a need to investigate the perceptual world of the dog, in particular, olfaction. What she calls “nosework.” She asks what it might be like “to be an olfactory creature, and how they can smell identity or smell quantity or smell time, potentially. I am always interested in the question: What is the smell angle here?”

Earlier this year, for instance, her group published a study, “Discrimination of Person Odor by Owned Domestic Dogs,” which “investigated whether owned dogs spontaneously (without training) distinguished their owner’s odor from a stranger’s odor.” Their main finding: Dogs were able to distinguish between the scent of a T-shirt that had been worn overnight by a stranger and a T-shirt that had been worn overnight by their owner, without the owner present. The result “begins to answer the question of how dogs recognize and represent humans, including their owners.”

It’s widely known and understood that dogs outsmell us, paws down. Humans have about six million olfactory receptors. Dogs as many as 300 million. We sniff indifferently and infrequently. Dogs, however, sniff constantly, five or ten times a second, and map their whole world that way. In fact, in a recent scientific journal article, Horowitz makes plain that olfaction is too rarely accounted for in canine cognition studies and is a significant factor that needs to be accorded much greater priority.

As I walked outside into the steady city drizzle, I thought back to Yale and to Winston, in his parallel universe of smell, making his way out of the lab, sniffing every hand and every shoe as we piled on our praise. Our worlds overlap, but aren’t the same. And as Winston fanned the air with his tail, ready to get back in the car for home, my hand light on his flank, I asked him the great unanswerable, the final question at the heart of every religious system and philosophical inquiry in the history of humanity.

“Who’s a good boy?”

* * *

So I sat down again with Laurie Santos. New Haven and Science Hill and the little white laboratory were all quiet under a late summer sun.

I wanted to explore an idea from Hare’s book, which is how evolution could select for sociability, friendliness, “goodness.” Over the generations, the thinking goes, eventually we get more affable, willing dogs—but we also get smarter dogs. Because affability, unbeknownst to anybody, also selects for intelligence. I saw in that a cause for human optimism.

“I think we’ve shaped this creature in our image and likeness in a lot of ways,” Santos tells me. “And the creature that’s come out is an incredibly loving, cooperative, probably smart relative to some other ancestral canid species. The story is, we’ve built this species that has a lot of us in them—and the parts of us that are pretty good, which is why we want to hang out with them so much. We’ve created a species that wants to bond with us and does so really successfully.”

Like Vanessa Woods and Brian Hare, she returns to the subject of human infants.

“What makes humans unique relative to primates?” she asks. “The fact that babies are looking into your eyes, they really want to share information with you. Not stuff that they want, it’s just simply this motivation to share. And that emerges innately. It’s the sign that you have a neurotypical baby. It’s a fundamental thread through the entire life course. The urge to teach and even to share on social media and so on. It makes experiences better over time when you’re sharing them with someone else. We’ve built another creature that can do this with us, which is kind of cool.”

* * *

I think of Winston more and more these strange days. I picture his long elegant face and his long comic book tail. His calm. His unflappable enthusiasm for problem-solving. His reasonability. Statesmanlike. I daydream often of those puppies, too. Is there anything in our shared history more soothing than a roomful of puppies?

There is not.

It turns out that by knowing the dog, we know ourselves. The dog is a mirror.

Logic; knowledge; problem-solving; intentionality; we can often describe the mechanics of how we think, of how we arrived at an answer. We talk easily about how we learn and how we teach. We can even describe it in others.

Many of us—maybe most of us—don’t have the words to describe how we feel. I know I don’t. In all of this, in all the welter of the world and all the things in it, who understands my sadness? Who can parse my joy? Who can reckon my fear or measure my worry? But the dog, any dog—especially your dog—the dog is a certainty in uncertain times, a constant, like gravity or the speed of light.

Because there is something more profound in this than even science has language for, something more powerful and universal. Because at the end of every study, at the end of every day, what the dog really chooses is us.

So. As I said. A love story.

:focal(294x74:295x75)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/69/c2/69c237b7-71cf-4164-ab9d-3641e68efdc1/yorkipoo-mobile.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ad/b7/adb7b95e-0765-437f-926d-58d955ad0b5e/socialmediadec2020_d08_caninecognition_2.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Jeff_MacGregor2_thumbnail.png)