New Technology Reveals Invisible Details in Renaissance Art

A team of Italian scientists has uses infrared light to detect artistic flourishes that are invisible to the naked eye

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20120619011033painting-small.jpg)

We’ve all heard it too many times to count: Don’t judge a book by its cover. A new technology indicates that we may have to start taking this approach when we look at historic artworks, too.

As detailed in a paper published yesterday in the journal Optics Express, a team of Italian scientists has pioneered a new way of revealing layers of paint and other materials that are invisible to the naked eye. The researchers applied their technique to a pair of legendary works of art: frescoes painted by the Zavattari family in the Chapel of Theodelinda, near Milan, and “The Resurrection” by the Italian Renaissance artist Piero della Francesca. The technology uncovered previously undetectable details in both of the works, such as pigments in the subjects’ armor that had been painted over during previous restorations.

“Our system easily identified old restorations in which missed gold decorations were simply repainted,” said lead author Claudia Daffara of the University of Verona. “ was also much better at visualizing armor on some of the subjects in the fresco.” The gold and silver embellishments, many of which were hidden by successive layers of dull paint during periodic restorations, shone brightly in images produced by the new technology.

Various other technologies, such as lasers and x-ray photography, have been employed to detect invisible details in art for decades. This time, though, the researchers used a different type of light to analyze the art works: mid-infrared wavelengths. The mid-infrared part of the spectrum includes light waves that are 3 to 5 micrometers long—much longer than the visible light we can detect with our own eyes, and slightly longer than the near-infrared waves used in traditional thermography techniques.

In addition to using the new wavelength, the research team’s approach went against the grain of established techniques in another way: Instead of utilizing the light naturally emitted by artworks, they tried to minimize it. Conventional thermography relies upon subtle differences in the amount of heat emitted by different pigments of paint to detect invisible details in art.

In this case, though, the scientists shined a faint mid-infrared light at the paintings using an artificial source (under-powered halogen lamps) and precisely measured the amount of light that reflected back. As a result, they got a brand-new picture of the underlying pigments and details hidden deep in the works. They call the technology TQR, for Thermal Quasi-Reflectography.

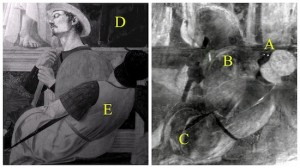

When applied to "The Resurrection," the new technology revealed (right) that the area near the solider sword was created using two different techniques. Photo courtesy of Optics Express

When applied to “The Resurrection,” TQR revealed several interesting features, including an area around the soldier’s sword that had been painted with a combination of two different fresco techniques—a detail that had been undetectable with conventional near-infrared imaging.

“For mural paintings the use of the mid-infrared regions reveals crucial details,” Daffara said. “This makes TQR a promising tool for the investigation of these artworks.” The authors are now planning to look into whether the system can be used to detect chemical differences in the paint pigments present on the surface of paintings.

The invisible details revealed by the new technology could potentially be used in future art restorations, as conservators seek to restore works as closely as possible to their original state. Because the technique does not damage the work, and can even be performed in the daytime hours during which museums are open to the public, we may soon see it adopted quickly by many in the world of art conservation.

TQR could theoretically be valuable in a whole host of other applications, too. For art historians, successive layers of painting and restoration can reveal valuable information about the context in which artworks were passed down and the circumstances of their owners and curators. The technology could someday even be applied to help detect forgeries.

Like other technological advancements we’ve covered recently—such as the method of learning about medieval books by measuring the amount of dirt on each page—the technique shows us just how much history is hidden within historical artifacts of all types. With paintings, as with books, there’s usually more than meets the eye.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/joseph-stromberg-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/joseph-stromberg-240.jpg)