Newly Discovered Bat-Like Dinosaur Reveals the Intricacies of Prehistoric Flight

Though Ambopteryx longibrachium was likely a glider, the fossil is helping scientists discover how dinosaurs first took to the skies

:focal(980x1104:981x1105)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/f6/4a/f64ae4a3-62a4-49f9-9835-edc80522ee1a/figure-c.jpg)

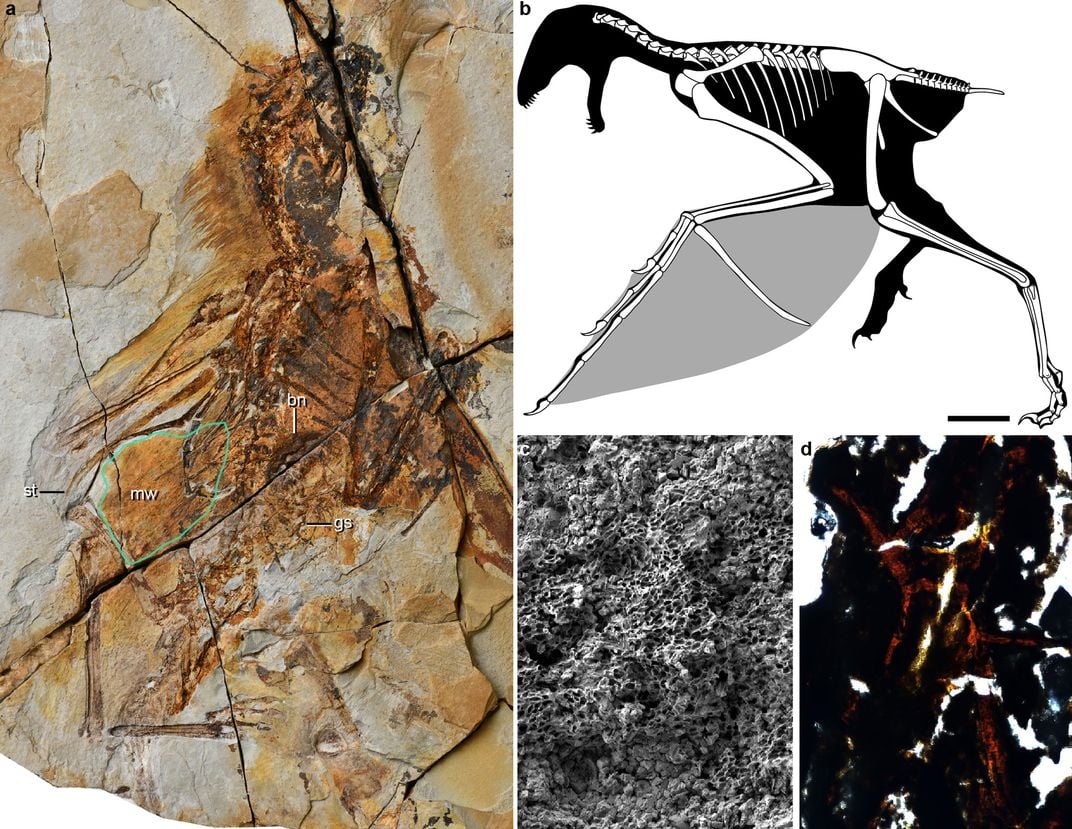

About 160 million years ago, in the depths of the Jurassic, feathered dinosaurs started to take to the air. Clawed arms that had evolved to snatch and catch began to take on a new aerodynamic role, and feather-coated limbs began flapping as the earliest avian dinosaurs overcame gravity to leave the surface of the Earth behind. But not all fluffy saurians launched into the air the same way. An unexpected discovery from China reveals an enigmatic family of dinosaurs with bat-like wings.

The first of these dinosaurs, given the adorable moniker Yi qi, was described by paleontologist Xing Xu and colleagues in 2015. While the small dinosaur had a coating of fuzz, its wings were primarily made up of a membrane stretched between the fingers and body. The dinosaur’s wings were more like those of bats, which wouldn’t evolve for more than 100 million years, or like the leathery wings of contemporary flying reptiles called pterosaurs.

Yi was unlike any dinosaur ever found—until now. Chinese Academy of Sciences paleontologist Min Wang and colleagues have just named a second bat-like dinosaur related to Yi in the journal Nature: Ambopteryx longibrachium.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/e3/0c/e30c08e3-4005-4caf-a90a-4075fde3755b/figure-d1.jpg)

“I was frozen when I realized that a second membranous winged dinosaur was in front of my eyes,” Wang says. The 163 million-year-old fossil confirms that Yi was not an aberration or a one-off. Together, the two species represent an alternate evolutionary path for airborne dinosaurs.

A delicately preserved skeleton surrounded by a splash of fossilized fuzz, with gut contents still inside the body cavity, Ambopteryx looks very similar to Yi. Both are close relatives within a group of small, fuzzy dinosaurs called scansoriopterygids. Ambopteryx differs from its relative in skeletal features, having a longer forelimb than hindlimb and fused vertebrae at the end of the tail that likely supported long feathers, but both represent a family of bat-like dinosaurs that was previously unknown to experts.

“It’s great to see another example of pterosaur-like wings in a scansoriopterygid,” says Washington University paleontologist Ashley Morhardt. The finding not only reinforces the case that such dinosaurs existed, but “paleontologists can now draw stronger biomechanical parallels between the wings of these dinosaurs and those of pterosaurs.”

Paleontologists are not sure exactly what these little dinosaurs were doing with their wings, however. “Ambopteryx and Yi were less likely to be capable of flapping flight,” Wang says. The dinosaurs may have been gliders, similar to flying squirrels of modern forests.

Additional studies could help reveal how these dinosaurs moved and any similarities to the flapping of early birds, Morhardt says. The brain anatomies of airborne dinosaurs, for example, can show specific functions related to flying, but unfortunately the little bat-like dinosaur specimens have been somewhat smooshed over geologic time. “Sadly, like many similar fossils, the skulls of Yi and Ambopteryx appear to be flattened like pancakes due to the pressure and time,” Morhardt says, making it impossible to get a good look at their brains.

Yet there’s more to Ambopteryx than its flapping abilities. The Ambopteryx skeleton is the best fossil of its family yet found, offering a more detailed look at the strange scansoriopterygids that have been puzzling paleontologists for years. Inside the body cavity of Ambopteryx are gizzard stones—tiny pebbles to help crush food—and fragments of bones. Along with the anatomy of the teeth, Wang says, the evidence suggests Ambopteryx and its relatives were probably omnivorous dinosaurs, gobbling up whatever they could.

The skeletal details of these dinosaurs will no doubt play into the ongoing debate about how some dinosaurs, including the first birds, started to flap and fly. Wang and colleagues call the two little dinos an “experiment” in the origins of flight. Ultimately, however, it didn’t take off. No dinosaurs like Yi or Ambopteryx have been found from the later Cretaceous period, when birds proliferated and pterosaurs of all sizes still soared through the skies. Yi and Ambopteryx represent another way dinosaurs took to the air, perhaps gliding from tree to tree to find food and shelter, but ultimately they were destined for the ground, preserved for 160 million years in the rocks of modern-day China for paleontologists to find and puzzle over while trying to piece together the mysteries of dinosaur flight.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RileyBlack.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RileyBlack.png)