Newly Discovered Comet, Headed Toward Earth, Could Shine as Bright as the Moon

Comet C/2012 S1(ISON) could become the brightest comet anyone alive has ever seen

![]()

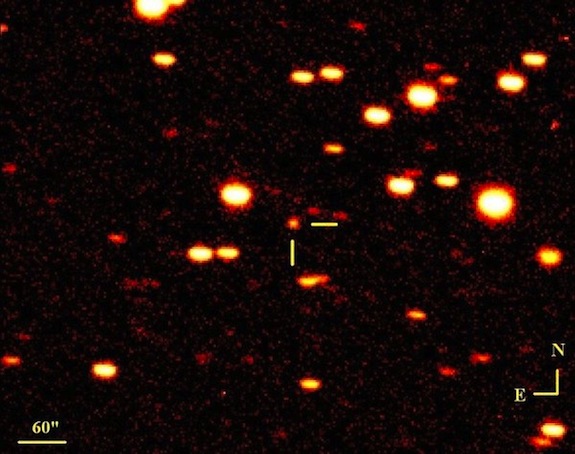

The newly discovered Comet ISON is at the crosshairs of this image, taken at the RAS Observatory near Mayhill, New Mexico. Image via E. Guido/G. Sostero/N. Howes

Last Friday, a pair of Russian astronomers, Artyom Novichonok and Vitaly Nevski, were poring over images taken by a telescope at the International Scientific Optical Network (ISON) in Kislovodsk when they spotted something unusual. In the constellation of Cancer was a point of light, barely visible, that didn’t correspond with any known star or other astronomical body.

Their discovery—a new comet, officially named C/2012 S1 (ISON)—was made public on Monday, and has since made waves in the astronomical community and across the internet.

As of now, Comet ISON, as it’s commonly being called, is roughly 625 million miles away from us and is 100,000 times fainter than the dimmest star that can be seen with the naked eye—it’s only visible using professional-grade telescopes. But as it proceeds through its orbit and reaches its perihelion, its closest point to the sun (a distance of 800,000 miles) on November 28th, 2013, it could be bright enough to be visible in full daylight in the Northern Hemisphere, perhaps even as bright as a full moon.

With current information, though, there’s no way of knowing for sure, and experts disagree on what exactly we’ll see. “Comet C/2012 S1 (ISON) probably will become the brightest comet anyone alive has ever seen,” wrote Astronomy Magazine’s Michael E. Bakich.” But Karl Battams, a comet researcher at the Naval Research Laboratory, told Cosmic Log, “The astronomy community in general tries not to overhype these things. Potentially it will be amazing. Potentially it will be a huge dud.”

Regardless, the coming year will likely see conspiracy theorists asserting that the comet is on a collision course with Earth (as was said about Elenin). Astronomers, though, are certain that we’re in no danger of actually colliding with Comet ISON.

Comets are bodies of rock and ice that proceed along elliptical orbits, traveling billions of miles away from the sun and then coming inward, turning sharply around it at high speeds, and then going back out. This cycle can take anywhere from hundreds to millions of years.

A comet’s distinctive tail is made up of burning dust and gases that emanate from the comet as it passes by the sun. Solar radiation causes the dust to incinerate, while solar wind—an invisible stream of charged particles that is ejected from the sun—causes gases in a comet’s thin atmosphere to ionize and produce a visible streak of light across the sky.

Ultimately, what Comet ISON will look like when it comes close depends on its composition. It could appear as a brilliant fireball, like the Great Comet of 1680, or it could disintegrate entirely before entering the inner solar system, like 2011′s Elenin Comet.

Its composition is difficult to predict because astronomers aren’t yet certain whether it is a “new” comet, making its first visit to the inner solar system from the Oort Cloud (a shell of comets that orbit the sun at great distance, roughly a light-year away) or whether it has passed us by closely before. “New” comets often burn more brightly while distant from the sun, as volatile ices burn off, and then dim when they come closer; returning comets are more likely to burn at a consistent rate.

One clue, though, indicates that its perihelion next year might be a sight to remember. Researchers have pointed out similarities between the path of this comet and of the Great Comet of 1680, which was visible in daytime and had a particularly long tail. If this is due to the fact that these two comets originated from the same body and at some point split off from each other, then Comet ISON might behave a lot like its 1680 cousin.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/joseph-stromberg-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/joseph-stromberg-240.jpg)