Newly Discovered Dinosaur Was a Giant ‘Shark Tooth’ Carnivore

Siamraptor suwati, discovered in Thailand, sliced flesh with razor-sharp teeth rather than crushing the bones of its prey

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/fc/e3/fce34041-7ad5-49c3-9661-8e370c3f9767/213047_web.jpg)

Tyrannosaurs are often seen as the kings of the prehistoric world. They’re among the largest and most charismatic of giant predators to stalk the Earth during the age of dinosaurs. But they weren’t the only voracious giants of the time. The “shark tooth lizards,” known to paleontologists as carcharodontosaurs, ruled all over the planet for tens of millions of years before and during the rise of tyrannosaurs, and a new find in southeast Asia helps fill in the backstory of these impressive carnivores.

A new species named Siamraptor suwati was found in the Early Cretaceous rock outcrops of Thailand. Dinosaurs can be difficult to find among the Mesozoic rocks of southeast Asia. Rock layers of the right age and type to find dinosaur bones are less abundant in this part of the world than places like the western United States or China, and those that do exist are often covered by thick forest. Yet, as reported today by Nakhon Ratchasima Rajabhat University paleontologist Duangsuda Chokchaloemwong and colleagues in the journal PLOS ONE, the bones of Siamraptor were found in 115-million-year-old rocks near the Thai district of Ban Saphan. The fossils were uncovered between 2008 and 2013 as part of a joint project with the Fukui Prefectural Dinosaur Museum in Japan.

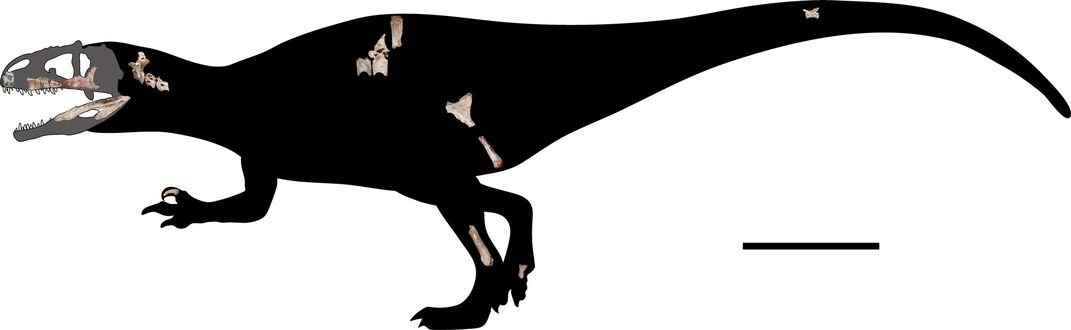

“From the first material we found, we knew right away this is an important specimen,” Chokchaloemwong says. All told, the bones of Siamraptor include parts of the spine, hips, feet, hands and skull. The dinosaur was an impressive hunter. At the place where Siamraptor was found, there are many carcharodontosaur teeth that match those of the newly named predator. Given that dinosaurs shed teeth throughout their lives, including when they ate, the Ban Saphan Hin site appears to have been a Siamraptor stomping ground.

Siamraptor now joins a bizarre and impressive array of carcharodontosaurs. Some members of this family bore strange ornaments on their backs, like the high-spined Acrocanthosaurus from the southern United States. Others, like Giganotosaurus from Argentina, grew to enormous sizes that matched or exceeded the great Tyrannosaurus rex. Carnivores like Siamraptor were apex predators in many of the places where tyrannosaurs failed to gain a claw-hold, and their anatomy underscores differences in how these dinosaurs behaved.

“At rough glance carcharodontosaurs and tyrannosaurs are broadly similar,” says University of Maryland paleontologist Thomas Holtz, Jr., as both are marked by “big heads, big bodies and short arms.” But digging into the details, the predators are very different. While the snouts of T. rex and kin are broad and round, Holtz says, carcharodontosaurs have “hatchet heads” with tall and narrow snouts fitted with blade-like teeth. The different snouts affect how these animals would have hunted and fed. “The bite in tyrannosaurids was bone-crushing like a hyena or an alligator, while that in carcharodontosaurs were more shark-like and slicing,” Holtz says.

While a dinosaur like Tyrannosaurus had a bite suited to crushing bone and wrenching muscle from the skeleton, dinosaurs like Siamraptor could open their mouths wide to slice large chunks of flesh while generally avoiding bone. Carcharodontosaurs feeding habits were almost like those of modern big cats, stripping flesh but largely leaving bones alone. But what makes Siamraptor particularly significant is what the find means for future discoveries.

Even though paleontologists had found carcharodontosaurs from the Early Cretaceous of North America, Europe and Africa, no one had found any fossils of the giant predators from the same time period in Asia. Siamraptor is the first and oldest definitive dinosaur of its family in southeast Asia, indicating that these imposing cousins of Allosaurus had spread to several ancient continents during the Early Cretaceous. The worldwide map of carcharodontosaurs had broad coverage during this time, Holtz says, but the discovery of Siamraptor adds one more dot where the family had not been found before. And there’s still more to discover. The frontiers of dinosaur discovery stretch everywhere. “From Thailand to Chile to Washington state,” Holtz says, “we are getting an ever-growing picture of the diversity in the world of dinosaurs.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RileyBlack.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RileyBlack.png)