Newly Discovered Tyrannosaur Was Key to the Rise of Giant Meat-Eaters

A partial skull found in Alberta helps put a timer on when the ‘tyrant lizards’ got big

:focal(403x137:404x138)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/4b/30/4b30a44f-f1c7-4e22-bb36-db54258a836c/thanatotheristes_low_rez_illustration_by_julius_csotonyi.jpg)

Paleontologists are uncovering tyrannosaurs at a fast and furious pace. The classic Tyrannosaurus rex may remain the most famous of all, but, in the last year alone, experts have described the bones of pipsqueaks that were far from the top of the food chain, leggy predators that lived in the shadow of other carnivorous giants, and short-snouted species that stalked the floodplains of the ancient west over 10 million years before the tyrant lizard king itself.

Now University of Calgary paleontologist Darla Zelenitsky has added another dinosaur to the tyrannosaur family, and this particular flesh-ripper reveals a surprise about the early days of the ferocious family.

The tyrannosaurs that roamed North America during the last 10 million years of the Cretaceous were large, impressive animals with equally menacing names. Dinosaurs such as Gorgosaurus, Albertosaurus, Daspletosaurus and Tyrannosaurus itself became rock stars thanks to multiple, well-preserved skeletons found from sites in Montana and the Dakotas, as well as the Canadian provinces of Saskatchewan and Alberta. But in the past ten years paleontologists have begun announcing even older tyrannosaurs found much farther south, among the roughly 80 million-year-old rocks of Utah and New Mexico. There didn’t seem to be any tyrannosaurs from rocks of similar age to the north. Until now.

The new dinosaur—described by University of Calgary graduate student Jared Voris, Zelenitsky and colleagues—is called Thanatotheristes degrootorum. That name might sound like a mouthful, but it’s fitting for an animal that is one of the oldest known from such a storied lineage. While the species name degrootorum honors amateur fossil hunters John and Sandra De Groot for discovering the fossil, the title Thanatotheristes is a combination of the Greek god of death, Thanatos, and the Greek word for “reap.” The dinosaur is announced today in Cretaceous Research.

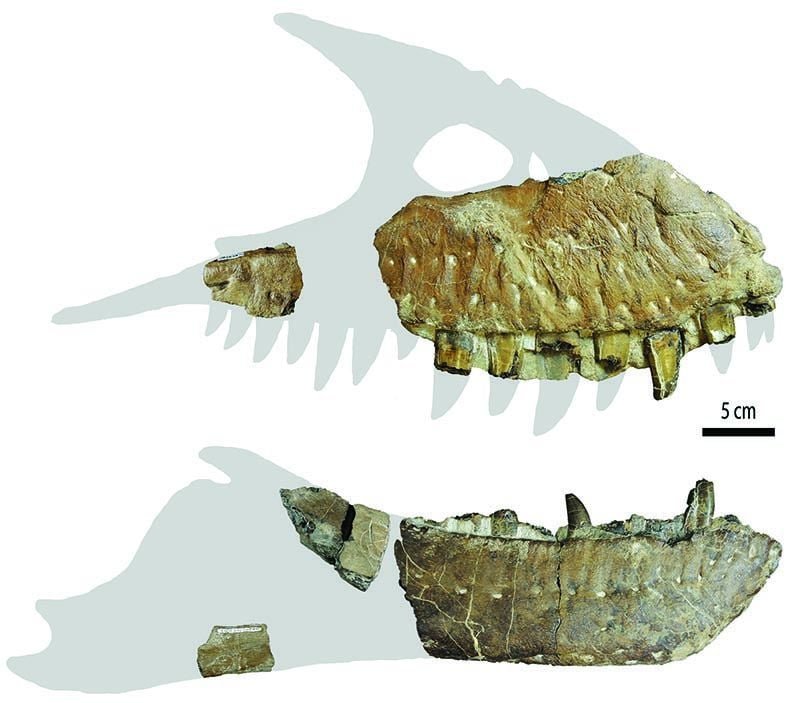

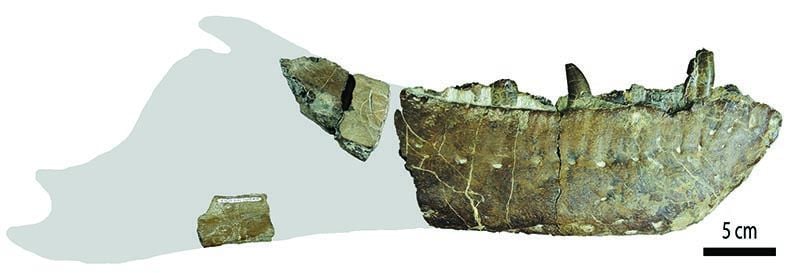

The importance of this dinosaur to the tyrannosaur story wasn’t immediately clear. In 2010, the De Groot family found parts of a dinosaur skull along the Bow River in southern Alberta. They contacted the Royal Tyrrell Museum, a hub for fossil research in the province that often oversees the excavation of significant finds according to Canadian heritage laws. The museum’s experts excavated the preserved parts—pieces of the jaws and back of the skull.

“The fossil was not initially thought to be new,” Zelenitsky says. The jaws, found in the roughly 79 million-year-old rock of the Foremost Formation, seemed like they belonged to another, already-known dinosaur. But, when Voris examined the bones during a trip to the Royal Tyrrell Museum collections, he noticed that these bones weren’t just another Daspletosaurus specimen. Subtle details of the fossils, such as the shape of the cheek bone and vertical ridges along where the teeth socketed into the upper jaw, indicated that the bones represented an animal never seen before.

“The new material is very incomplete and the differences between Thanatotheristes and Daspletosaurus are relatively subtle,” says Royal Ontario Museum paleontologist David Evans, but, he notes, “the age of the new material makes it likely that the animal is something new.” The bones are about 2.5 million years older than other tyrannosaurids found in Alberta, and come from rocks that can be stubborn about giving up fossils. “My crews have been searching the rocks of the Foremost Formation for almost 20 years, and we have found only teeth and rare isolated bones of tyrannosaurs,” Evans says.

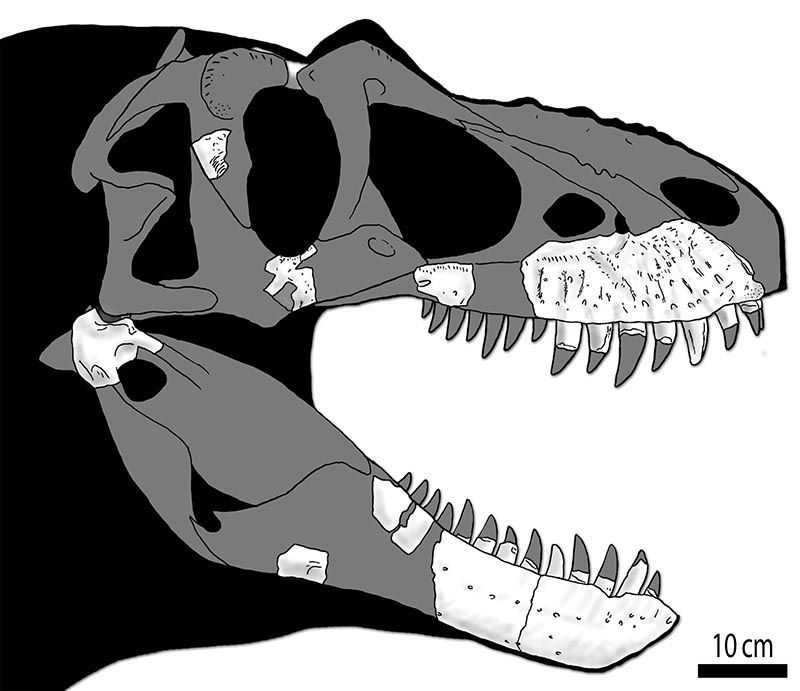

In life, Thanatotheristes was a large animal. The complete skull of this individual would have measured about three feet in length, Zelenitsky says, and, through comparisons with related tyrannosaurs, the experts estimate a body length of about 26 feet. That’s comparable to the later, well-known tyrannosaurs of the area like Gorgosaurus, even if it is on the short size of the largest, 40-foot-long T. rex.

What really makes Thanatotheristes stand out, however, is when it lived. The tyrannosaurs have a family rooted deep in the Jurassic, over 150 million years ago, but these carnivores remained small for most of their history. It wasn’t until late in the Cretaceous that tyrannosaurs really became large and in charge in North America. These dinosaurs are recognized within a subgroup called tyrannosaurids, and Thanatotheristes is among the oldest—if not the oldest—member of this group. The recent announcement of large tyrannosaurs of similar age from the south, such as Lythronax from Utah and Dynamoterror from New Mexico, all underscore the fact that tyrannosaurids were imposing predators by about 80 million years ago at the latest.

As these new finds are compared to one another, a more complex tyrannosaur story is emerging. The tale of these awesome predators isn’t simply a matter of ever-increasing size and bone-crushing power. “There seems to be different types of related tyrannosaurs in different geographic regions, which vary in skull form and shape,” Zelenitsky says. While some similar-aged tyrannosaurs from southern regions have short, “bulldog-like” snouts, Zelenitsky notes, northern tyrannosaurs such as Thanatotheristes and Daspletosaurus have comparatively longer snouts.

“The idea that different lineages radiated in different areas of the western interior of North America is bolstered by the new analysis,” Evans says, and seems to indicate that different tyrannosaur species lived in distinct areas between 80 and 75 million years ago. That contrasts with the range of the later T. rex which was the lone tyrannosaur from Canada to the southwestern U.S. by 68 million years ago.

Why tyrannosaurs in different regions should have noticeably different snout shapes isn’t yet clear. Perhaps the changes are related to their ancestry and represent branching off from even older ancestors that have yet to be uncovered. Or perhaps the variations in profile indicate different diets or feeding habits. Long-snouted carnivores often bite faster, while short-snouted carnivores often bite harder. More fossils are needed to be certain. And they are certainly out there. Somewhere in western North America, in rocks more than 80 million years old, there must be the fossilized remains of the tyrannosaurs that started the family’s impressive reign.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RileyBlack.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RileyBlack.png)