Nitpicking the Lice Genome to Track Humanity’s Past Footsteps

Lice DNA collected around the planet sheds light on the parasite’s long history with our ancestors, a new study shows

![]()

A male human head louse. Photo by Flickr user Gilles San Martin

Parasites have been around for more than 270 million years. Around 25 million years ago, lice joined the blood-sucking party and invaded the hair of ancient primates. When the first members of Homo arrived on the scene around 2.5 million years ago, lice took advantage of the new great ape on the block for better satisfying its digestive needs. As a new genetic analysis published today in PLoS One shows, mining these parasites’ genomes can lend clues for understanding the migration patterns of these early humans.

The human louse, Pediculus humanus, is a single species yet members fall into two distinct camps: head and clothing lice–the invention of clothing likely put this divide into motion. Hundreds of millions of head lice infestations occur each year around the world, most of them plaguing school-aged children. Each year in the United States alone, lice invade the braids and ponytails of an esimtated 6 to 12 million kids between the ages of 3 to 11. Clothing lice, on the other hand, usually infect the homeless or people confined to refugee camps. Clothing lice–also referred to as body lice–are less prevalent but potentially more serious because they can serve as vectors for diseases such as typhus, trench fever and relapsing fever.

Researchers have studied the genetic diversity of head and clothing lice in the past, but scientists from the Florida Museum of Natural History at the University of Florida decided to tap even deeper into the parasites’ genome, identifing new sequences of DNA that could be used as targets for tracking lice evolution through time and space. From these efforts, they found 15 new molecular markers, called microsatellite loci, which could help uncover the genetic structure and breeding history behind different lice populations–and potentially their corresponding humans of choice.

Using those genetic signals, they analyzed the genotypes of 93 human lice taken for 11 different sites around the globe, including North America, Cambodia, Norway, Honduras, the UK and Nepal, among others. They collected lice from homeless shelters, orphanages and lice eradication facilities.

Inbreeding, it turned out, is common in human lice around the world. Lice in New York City shared the most genetic similarities, pointing to the highest levels on inbreeding from the study samples. Clothing lice tended to have more diversity than head lice, perhaps due to an inadvertent bottlenecking of the head lice population due to high levels of insecticides those parasites are regularly exposed to. As a result of repeated run-ins with anti-lice shampoos and sprays, only the heartiest pests would survive, restraining the overall diversity of the population. Insecticide resistance is a common problem in head lice, but less of an issue with clothing lice. The authors identified one possible gene that may be responsible for much of the head louse’s drug resistance, though further studies will be needed to confirm that hunch.

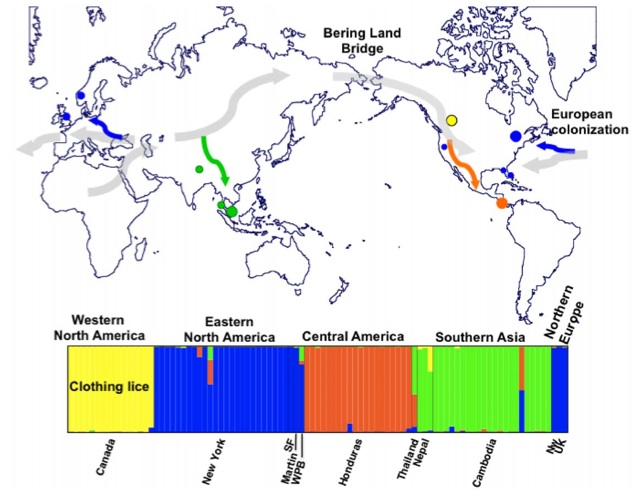

The researchers also analyzed lice diversity to see how it relates to human migration. They found four distinct genetic clusters of lice: in clothing lice from Canada, in head lice from North America and Europe, in head lice from Honduras and in all Asian lice.

Here’s the authors present a map of lice genetic diversity. The colored circles indicate sampling sites, with the different colors referring to the major genetic clusters the researchers identified. The grey flowing arrows indicate proposed migrations of modern humans throughout history, and the colored arrows represent the hypothetical co-migration of humans and lice.

Photo from Ascunce et al., PLoS One

How this geographic structure reflects human migration, they write, will require more sampling. For now, they can only speculate about the implications:

Although preliminary, our study suggests that the Central America-Asian cluster is mirroring the (human host) colonization of the New World if Central American lice were of Native American origin and Asia was the source population for the first people of the Americas as has been suggested. The USA head louse population might be of European decent, explaining its clustering with lice from Europe. Within the New World, the major difference between USA and Honduras may reflect the history of the two major human settlements of the New World: the first peopling of America and the European colonization after Columbus.

Eventually, genetic markers in lice could help us understand interactions between archaic hominids and our modern human ancestors, perhaps answering questions such as whether or not Homo sapiens met with ancient relatives in Asia or Africa besides Homo neanderthalensis. Several kinds of louse haplotypes, or groups of DNA sequences that are transmitted together, exist. The first type originated in Africa, where its genetic signature is strongest. A second type turns up in the New World, Europe and Australia, but not in Africa, suggesting that it may have evolved first in a different Homo species whose base was in Eurasia rather than Africa. If true, then genetic analysis may give us a time period for when humans and other Homo groups for came into contact. And if they interacted close enough to exchange lice, perhaps they even mated, the researchers speculate.

So not only can the genetic structure of parasite populations help us predict how infections spread and where humans migrated, it may give insight into the sex-lives of our most ancient ancestors.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Rachel-Nuwer-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Rachel-Nuwer-240.jpg)