North to Alaska

In 1899, railroad magnate Edward Harriman invited preeminent scientists in America to join him on a working cruise to Alaska, then largely unexplored

For c. hart merriam, it all began one March day in 1899 when a brash fellow with a bushy mustache strode unannounced into his Washington, D.C. office. Merriam, a distinguished biologist and a founder of the National Geographic Society, was serving as the first chief of the Division of Biological Survey, the forerunner of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. His visitor identified himself as Edward Harriman. “He . . . told me in an unassuming, matter-offact way that he was planning a trip along the Alaskan coast,” Merriam later recalled, “and desired to take along a party of scientific men.” Harriman then asked Merriam to recruit those scientists for him—adding that he would, of course, pay everyone’s expenses.

When Merriam found out that Edward Harriman was the E. H. Harriman who chaired the board of the Union Pacific Railroad and was reputed to be the most powerful man in America, he began firing off telegrams to his many acquaintances in the scientific world: “Mr. Harriman requests me to ask you to join . . . and I earnestly trust you will do so. The opportunity is one in a lifetime.”

He was right about that. Harriman was nothing if not ambitious: he wanted to catalog Alaska’s flora and fauna from the lush southern panhandle north to Prince William Sound, then west along the Aleutian Chain and all the way up to the Pribilof Islands. His exhilarated corps of “scientific men,” it turned out, discovered hundreds of new species, charted miles of little-visited territory and left such a vivid record of their findings that a century later a second expedition set out to assess the changes that have taken place along that same route. (On June 11, most PBS stations will broadcast a two-hour Florentine Films/Hott Productions documentary about both voyages.)

As it was in his own time, Harriman’s 9,000-mile odyssey is still being hailed as a scientific milestone. “It was the last of the great Western explorations that began with Lewis and Clark,” says William Cronon, professor of environmental studies at the University of Wisconsin. A contemporary parallel, says historian Kay Sloan, author with William Goetzmann of Looking Far North: The Harriman Expedition to Alaska, 1899, “would be Bill Gates leading a scientific expedition to the moon.”

At least we can see the moon. Alaska at 19th century’s end was the ultimate back of beyond as far as most Americans were concerned. After President Andrew Johnson’s wily secretary of state William H. Seward—first appointed by Lincoln bought the territory in 1867 for $7.2 million, he was roundly thumped in the press. “Russia has sold us a sucked orange,” groused one New York newspaper. Some orange—more than half a million square miles, an area twice the size of Texas, encompassing 39 mountain ranges, 3,000 rivers and upwards of 2,000 islands. Three decades after “Seward’s Folly,” Alaska remained one of the largest unexplored wildernesses on the continent.

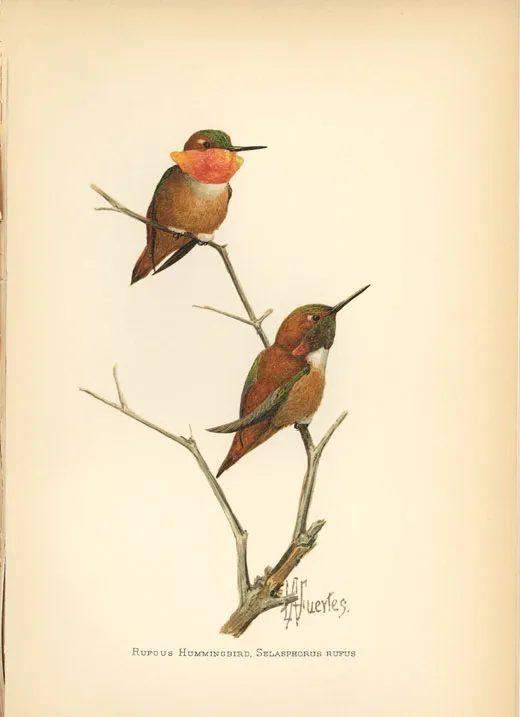

It took Merriam only a few weeks to sign up 23 of the most esteemed scientists in their fields, plus a cadre of artists, photographers, poets and authors. Among them were nature writers John Burroughs and John Muir; George Bird Grinnell, the crusading editor of Forest and Stream and a founder of the Audubon Society; a young painter of birds, Louis Agassiz Fuertes, and an obscure society photographer named Edward Curtis. Not surprisingly, Merriam also decided to avail himself of Harriman’s hospitality.

All in all, it was probably the most high-powered group ever assembled in the history of American exploration. But would so many big thinkers be able to get along? “Scientific explorers are not easily managed, and in large mixed lots are rather inflammable and explosive,” Muir warned, “especially when compressed on a ship.”

But, oh, what a ship. Harriman, it was clear, did not intend to rough it. He had refitted the 250-foot-long iron steamer George W. Elder with a stateroom for each expedition member. The crew alone numbered 65—not counting the ten other members of Harriman’s family, their three maids, two stenographers, two doctors, a nurse, an excellent chef and a chaplain. “We take aboard eleven fat steers, a flock of sheep, chickens, and turkeys, a milch cow, and a span of horses,” John Burroughs crowed. Other essential items included cases of champagne and cigars, an organ and piano, a 500-volume library and even an early gramophone.

On May 31, 1899, a cheering crowd gathered at the Seattle dock to watch the Elder steam away in slanting rain, and the departure made front-page news all over the world. But for any passenger who believed he or she was heading for a pristine Eden, some rude surprises were in store.

Six days out of Seattle in Skagway, a quagmire of flimsy hotels and saloons and a jumping-off point for the Yukon goldfields, the Harriman party confronted the gritty reality of the spreading Klondike gold rush. During an outing on the new White Pass Railroad, built to carry miners up into the mountains, the scientists saw carcasses of horses frozen on the rugged trail. Later, near Orca, “Miners were coming out destitute and without one cent’s worth of gold,” Burroughs wrote. “Scurvy had broken out among them. . . . Alaska is full of such adventurers, ransacking the land.”

But Alaska was full of astonishments too. When the Elder steamed into Glacier Bay, west of Juneau, on June 8, Burroughs was amazed. “Enormous [ice]bergs . . . rise slowly and majestically, like huge monsters of the deep . . . , ” he marveled. “Nothing . . . had prepared us for the color of the ice . . . its deep, almost indigo blue.” Burroughs, then America’s favorite nature writer, was a small, mild man who had spent most of his life in New York’s benign Catskill Mountains. Alaska scared him: “[I]t was as appalling to look up as to look down; chaos and death below us, impending avalanches of hanging rocks above us.”

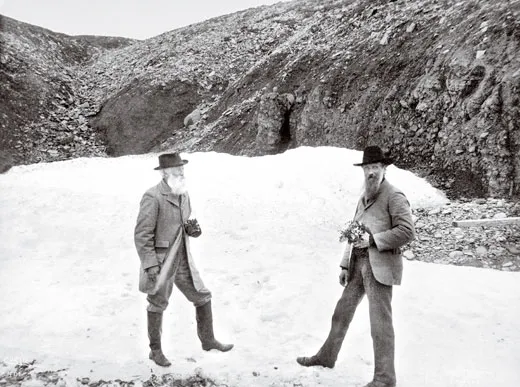

The trip’s other Johnny was right at home in Alaska. Born in Scotland, John Muir had grown up on an isolated Wisconsin farm, then adventured for years in the rugged wilds of California’s Yosemite Valley. There he began writing about the natural world and started the Sierra Club. He was the country’s foremost champion of wilderness and had visited Alaska no less than five times, including months in Glacier Bay. “In John Muir we had an authority on glaciers,” Burroughs said, “and a thorough one—so thorough that he would not allow the rest of the party to have an opinion on the subject.”

It was no surprise two men so different in temperament and background did not always see eye to eye, particularly when it came to Edward Harriman. Burroughs liked him, but Muir was “rather repelled” by the seemingly coldhearted businessman, perhaps not least because Harriman cherished a sport Muir detested: hunting. In fact, the railroad man’s dream was to shoot and mount a giant Alaskan brown bear, and to that end he had brought along a complement of 11 hunters, packers and camp hands, plus two taxidermists.

In a sense, the restless tycoon had been hunting all his life—for success. The son of a minister in New York, Harriman had grown up in a family that had seen better days. He quit school at 14 to become a Wall Street errand boy. His rise from that humble station was meteoric. At 22, he became amember of the New York Stock Exchange. At 33, he acquired his first rail line. He seized control of the huge but ailing Union Pacific Railroad at 50, then spent months inspecting every mile of track, every station, flatcar and engine. He got his railroad running smoothly, but in the process he drove himself to exhaustion. When his doctor told him to get some rest, Harriman, then 51, decided to “vacation” in Alaska.

His reasons for sponsoring the expedition have long been debated. Harriman himself painted a rosy picture: “What I most enjoy is the power of creation, getting into partnership with Nature in doing good . . . making everybody and everything a little better.” Some of his contemporaries believed he had more complicated motives. “He was looked at askance [by New York’s social elite],” one acquaintance observed. “His ways and manners jarred somewhat . . . and he was considered by some as not quite belonging.” The trip could help. Then, too, this was an age of magnificent engineering breakthroughs like the Suez Canal, the EiffelTower and the BrooklynBridge. Kay Sloan and William Goetzmann believe Harriman wanted to accomplish a similar feat. His aim, they contend, was to scout out and buy up a huge swath of Alaska and build a railroad to Siberia and on around the world.

Whatever his ultimate ambition, there was no doubting Harriman’s commitment to scientific exploration. The ship “put us ashore wherever we liked,” Muir reported, “bays, coves, the mouths of streams, etc.—to suit [our] convenience.” At Glacier Bay, zoologist Trevor Kincaid pried open icy crevices and found “glacier worms,” a type of rare tube worm. Ornithologists Albert Fisher and Robert Ridgway, with artist Louis Agassiz Fuertes, collected 45 mammals and 25 birds at Point Gustavus. Another scientist found a nesting ptarmigan so tame it could be picked up and held.

In mid-June, the Elder steamed across the Gulf of Alaska to YakutatBay near the western border of Canada. Kincaid and his fellow zoologists discovered 31 new insects and captured 22 different kinds of mice.

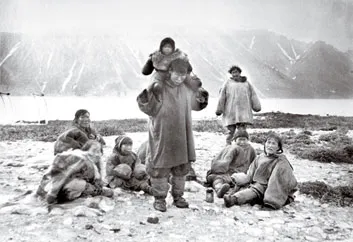

The steamer anchored near an encampment of seal-hunting Indians on the south side of the bay. Rank-smelling carcasses lay in rows on the pebbly beach. George Bird Grinnell watched with fascination as women and children skinned the animals, cut out the blubber and roasted seal meat over an open fire. “From the [tent] poles hang . . . strips of blubber and braided seal intestines,” Grinnell noted. “All these things are eaten . . . the flippers appear to be regarded as especially choice.”

Though most of the scientists had come to study glaciers and mountains or wildlife and plants, Grinnell, an expert on the Indians of the American West, was more interested in documenting the lives of northern peoples. It didn’t take him long to discover that he had an able assistant in the young photographer Edward Curtis.

Curtis had made a modest living in Seattle photographing wealthy socialites at their weddings and balls. Now, under Grinnell’s influence, Curtis started focusing on Alaska’s natives. “The . . . Indian women frowned upon our photographers,” Burroughs said. “It took a good deal of watching and waiting and maneuvering to get a good shot.” But Curtis was patient. Although he could not have known it at the time, he had found his life’s vocation.

From YakutatBay the expedition headed north to Prince William Sound, the ravishing area that would eventually come to exemplify Alaska for millions of cruise ship tourists. The tiny village of Orca, the Elder’s first stop there, was dominated by an enormous fish cannery. Seeing miles of coastline clogged with rotting salmon heads, Grinnell was irate. “The canners . . . [grasp] eagerly for everything that is within their reach,” he fumed. “Their motto seems to be, ‘If I do not take all I can get, somebody else will.’. . . The salmon of Alaska . . . are being destroyed.”

Beyond Orca, the Elder churned deeper into Prince William Sound until it came up against a towering glacier, which, according to the map, was as far as the ship could go. After Muir spotted a narrow gap between the ice and the rocky coast, Harriman ordered the captain to steer into the dangerously tight passage. Poet Charles Keeler described the moment: “Slowly and cautiously we advanced. . . . The great blocks of ice thundered off from the glacier into the sea close beside us.” Then the ship rounded a point, and a narrow inlet suddenly became visible. The captain warned that there might be rocks in those uncharted waters. According to Muir, “The passage gradually opened into a magnificent icy fiord about twelve miles long.” Harriman ordered the captain to proceed full speed ahead up the middle of the new fjord. As the ship barreled along, Harriman shouted, “We will discover a new Northwest Passage!”

Instead they discovered a dazzling series of glaciers—five or six in all—never before seen by whites. The largest glacier was named after Harriman. Muir’s feelings for the man were changing from scorn to admiration. “I soon saw that Mr. Harriman was uncommon,” he explained. “Nothing in his way could daunt him.”

But Harriman, tired of “ice time,” was itching for big game. When he heard of abundant bear on Kodiak Island, he ordered the ship there. After the glacial “ice chests” they’d just seen, verdant Kodiak, warmed by the Japan Current, was paradise for Burroughs. But Muir was grumpy. “Everybody going shooting, sauntering as if it were the best day for the ruthless business,” he complained.Harriman finally found a big bear “eating grass like a cow.” He killed it with a single shot, then photographed the animal with her enormous teeth bared.

Even without news of felled bears, life aboard the Elder was anything but dull. There were lectures on everything from whaling to Africa and evening musicals with jigs and Virginia reels. One night, Muir, as botanist Frederick Coville put it, “did a neat double-shuffle, immediately followed by [the 63-year-old] Mr. Burroughs, who stepped forward . . . and gave an admirable clog-dance . . . an astonishing exhibition of agility in an old man with a white hair and beard.” Forester Bernhard Fernow played Beethoven on the piano. The worthy gentlemen of the Harriman Alaska Expedition even came up with a cheer: “Who are we? Who are we? We are, we are, the H.A.E.!”

But when the Elder stopped at DutchHarbor, a peaceful little town on the island of Unalaska, a seasick and cold John Burroughs tried to jump ship. “Mr. Muir and I were just returning to the steamer when we saw John Burroughs walking down the gangplank with a grip in his hand,” Charles Keeler recalled. “ ‘ Where are you going, Johnny?’ demanded Muir suspiciously. . . . [Burroughs] confessed. He had found a nice old lady ashore who had fresh eggs for breakfast.” Burroughs said he would wait there while the Elder took on the Bering Sea. “ ‘Why Johnny,’ explained Muir derisively, ‘Bering Sea in summer is like a mill pond.’ ” Burroughs, said Keeler, “could not withstand Muir’s scorn. I carried his satchel back to his room, and . . . he returned to the steamer.”

Muir was wrong. With its barren islands and notoriously rough weather, the Bering Sea was not remotely like a millpond, but C. Hart Merriam loved it all the same. He had been there in 1891 to inspect the commercial harvesting of fur seals. Now he waded eagerly onto the desolate rocks of volcanic BogoslofIsland, only to find himself standing in the middle of a “runway” where sea lions weighing as much as a ton thundered down toward the water. “A number of huge yellow bulls, as big as oxen . . . came toward us bellowing fearfully.” For a moment Merriam thought “the end had come.” Impulsively, he ran toward the sea lions with his camera, and “most took fright and made off.”

After the Elder anchored at the Pribilofs the next day, the expeditioners tramped across flower-covered fields on St. PaulIsland to visit a huge fur-seal rookery Merriam had seen there during his previous visit. But when he caught his first glimpse, he gasped in horror, “astonished,” said Burroughs, “at the diminished number of the animals—hardly one tenth of the earlier myriads.”

It proved to be a crucial moment. When Grinnell got back to New York, he wrote a passionate editorial in Forest and Stream predicting that the beleaguered seals would soon become extinct. Merriam lent the weight of his own considerable influence to a campaign to force the federal government to take action. In 1912, the United States, Russia, Japan and Canada finally agreed to impose limits on seal hunting. The treaty they signed, the first international agreement for protecting wildlife, grew out of the Harriman party’s visit to the Pribilofs.

After nearly two months at sea, Edward Harriman said he didn’t “give a damn if I never see any more scenery” and declared himself ready to go back to work. The Elder swung around and headed south. But on its return, the ship made an unscheduled stop opposite St. Mary’s Island at a Tlingit village near CapeFox. There the expedition members saw a dozen or so magnificent totem poles towering over a collection of seemingly abandoned houses on the sandy shoreline. “It was evident the village had not been occupied in . . . years,” said Burroughs. “Why not, therefore, secure some of these totem poles for the museums of the various colleges represented by members of the expedition?”

The artist Frederick Dellenbaugh described what happened next: “Agang started to take down some of the totems and as they were twenty to forty feet high, and three or more [feet] in diameter at the base, this was no light task. I heard a great deal of tugging and fuming. . . . When I got through my sketch I went over and helped. We found it pretty hard work to move the next one even with rollers and tackle fastened to the rocks seaward and twenty men pulling. It was very hot on shore. And I was thoroughly warmed through for the first time since leaving Seattle.”

John Muir was hot, too—about the totems. As far as most of the scientists were concerned, they were merely gathering artifacts; to Muir, it was pillaging plain and simple. Disgusted, he stomped off. When Edward Curtis took a celebratory photograph of the whole party, with their trophy totems in the background, the angry Scot refused to pose.

The day after the Elder reached home port at the end of July, with 100 trunks full of specimens, the Seattle Post-Intelligencer fairly beamed its approval. “All things favored Mr. Harriman in carrying out his plans for the greatest junket probably in the history of the nation. . . . The scientists . . . ransacked the water below, the lands about, and the heavens above for swimming, creeping, and flying things, named and nameless. When the Elder landed in Seattle yesterday morning, she resembled a floating curiosity shop.”

Not to be outdone, the Portland Oregonian chimed in: “No more able group of scientists has set sail on a voyage of this kind in recent years. Mr. Harriman has done his country and the cause of human learning a signal service.”

The expedition’s treasures were destined to become the basis of major collections at the Smithsonian and other leading institutions, including HarvardUniversity, the FieldMuseum in Chicago and the University of Washington. Harriman’s scientists described 13 new genera and nearly 600 new species, as well as many fossil species. The artists had made more than 5,000 photographs and paintings of plants and animals, natural wonders and native peoples. The coast of Alaska was a mystery no more.

The expedition’s importance “created a picture of a place that was still largely unknown to most Americans,” says Harriman’s biographer, Maury Klein. “Those who thought of Alaska as untouched wilderness, only slightly blemished by the gold rush and the cannery business, were surprised by the expedition’s evidence of how much it had already started to change.” Robert Peck, a fellow of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia, believes “those scientists were among the first to struggle with how to balance the pristine nature of Alaska’s wilderness with the world’s demand for its resources. Together they created a baseline of information that is still used today.”

Jim Bodkin, an otter specialist who works for the U.S. Geological Survey in Glacier Bay, is one of the users. “Science is a process of building upon knowledge that has been gathered in the past,” he says. “And so it’s absolutely essential for us to have the information those prior scientists made available. What we do today is based on what they did a century ago.”

At journey’s end, John Burroughs happily resumed rusticating in his beloved Catskills, but for other expedition members there would be no return to the status quo. When Harriman decided to gather the expedition’s scientific findings into a book, he turned once again to Merriam and asked him to be the editor. The old biologist spent the next 12 years working on the “book,” which grew to an astounding 13 volumes before it was finished.

George Bird Grinnell went back to New York City and devoted much of his considerable energy to crusading in Forest and Stream for the conservation of Alaska’s wildlife. Edward Curtis devoted the rest of his life to photographing the vanishing tribes of North America. He took more than 40,000 images, reproducing many of them in his monumental 20-volume work, The North American Indian.

John Muir’s improbable friendship with Edward Harriman paid off in 1905, when the intrepid wilderness advocate was struggling to get part of Yosemite Valley protected as a national park. He asked Harriman for help, and the railroad man’s powerful lobbying in the U.S. Senate enabled the Yosemite bill to pass by a single vote. Harriman’s power continued to grow in the years after the Alaska expedition. He merged the Union Pacific and Southern Pacific railroads, but then an antitrust suit pulled them apart. Although that suit helped turn public opinion against Harriman, Muir stuck by him. When Harriman died in 1909, it was Muir who wrote his eulogy. “In almost every way he was a man to admire,” he said. “I at last learned to love him.”

Alaska Then and Now

A commemorative voyage—of 21st-century scientists—sets out to reconnoiter the 49th state

ECOLOGY IS DEDICATED to the proposition that everything is connected to everything else, as Thomas Litwin, an ecologist and science administrator at SmithCollege in Northampton, Massachusetts, can attest. Studying ornithology at CornellUniversity in 1979, he fell in love with a collection of bird illustrations there by Louis Agassiz Fuertes, a member of the Harriman Alaska Expedition. That led to a lifelong obsession with the expedition itself. Nearly two decades later, Litwin began having “crazy daydreams” about organizing a reprise of the trip to commemorate its 100th anniversary. Those dreams became a reality on July 22, 2001, when Litwin, then 51, escorted 24 scientists, scholars and artists he had gathered together from across the country onto the cruise ship Clipper Odyssey bound from Prince Rupert, British Columbia, to a rendezvous with history.

Called the Harriman Alaska Expedition Retraced, the second voyage set out “to assess a century of environmental and social change,” as Litwin put it. “We’re seeing this landscape at two moments in time,” said William Cronon, a professor of environmental studies at the University of Wisconsin and one of Litwin’s “Harriman scholars.” “We’re seeing it through the eyes of that earlier expedition and we’re seeing it now at the beginning of the 21st century, and we’re asking: What’s the shift?”

The 2001 party took pains to follow the original Harriman route and, like its predecessor, bristled with all the latest gadgetry—GPS mapping, satellite photography and cell phones. But there were differences. For one thing, half of Litwin’s expedition was made up of women and Alaska Natives. For another, Harriman Retraced made no bones about doing handson science. “A lot of researchers are engaged in important work all up and down the coast,” said Lawrence Hott, a documentary filmmaker who accompanied the group. “The idea here is to take a broader look at issues that continue to play out today, just as they did in Harriman’s time—boom-and-bust cycles, pollution, wilderness preservation, respect for native cultures.”

The 30-day excursion turned out to be a study in contrasts. In 1899, for example, the eminent forester Bernhard Fernow gazed at a great rain forest and announced that it would be “left untouched” because it wasn’t commercially viable. When the voyagers of Harriman Retraced visited that same forest, now known as the Tongass, they saw a patchwork of clearcuts that have enraged conservationists across the country. To C. Hart Merriam and his awed recruits, Prince William Sound looked as pristine as Eden. Litwin’s group found it still recovering from the disastrous effect of the 1989 Exxon Valdez oil spill. Alaska had changed, and not necessarily for the better.

During the first half of the 20th century, the rugged settlers of the Far North struggled through one bust after another—gold, salmon, copper. Alaska finally struck it rich after major oil deposits were discovered on the Kenai Peninsula in 1957, but by 2001 a new boom was under way: tourism.

When Harriman’s men visited Skagway, it was a squalid wilderness outpost overrun with miners. Harriman Retraced witnessed a quite different scene—a “gold rush” theme park overrun with sightseers. “It felt like Disneyland,” said a dismayed Kathryn Frost, a marine-mammal researcher with the Alaska Department of Fish and Game.

By 1899, a few steamers had begun transporting tourists to Glacier Bay, much to John Muir’s consternation. In 2001, the Clipper Odyssey was but one of several dozen cruise ships anchoring there; the total number of passengers that summer exceeded 600,000. “A lot of us who came up here seeking something different are watching Alaska relentlessly becoming just like every other place in the United States,” former Alaska governor Jay Hammond told documentarian Hott.

Wildlife, at least, has rebounded dramatically from overhunting in the years before the first expedition. In YakutatBay, Edward Harriman bought a pelt said to be that of the last wild sea otter. Litwin’s party encountered hundreds of otters, flourishing again thanks to a 1911 protection act and a reintroduction program begun in 1969.

Salmon, too, are back. In the years after George Bird Grinnell anguished over their plight at Orca, the fish became so scarce that many canneries went out of business. When Alaska became a state in 1959, it was able to set tough fishing limits that eventually restored teeming salmon runs to many rivers. But by 2001, Bob King, press secretary to then-governor Tony Knowles and a salmon expert in his own right, was concerned that some populations were in trouble again. “This cries out for many of the things Grinnell was saying back in 1899,” he said. “We need more scientific inquiry. We need to know what’s going on with those fish. And we need stronger enforcement of fishing rules.”

DutchHarbor, the sleepy little village where John Burroughs tried to jump ship, is now one of the most productive fishing ports in the United States; scientists fear it may be undermining the entire Bering Sea ecosystem. The annual harvest of just one species of fish, pollock, exceeds a million metric tons a year. Stellar sea lions, a species in serious trouble, eat pollock. Although many environmentalists insist the way to save sea lions is to limit fishing, experts aboard the Clipper Odyssey weren’t so sure. “It’s probably overly simplistic to think that is going to bring the sea lions back,” said Kathryn Frost. “We’re feeling very helpless about it. We don’t know what to do.”

Of all those touched by change in Alaska, no one has been more profoundly affected than its native peoples. Back in 1899, George Bird Grinnell predicted their demise, but in 1971 Congress passed the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act which, by ceding 44 million acres and nearly a billion dollars, gave the state’s some 50,000 Eskimos, American Indians and Aleuts a full stake in its economy and its future. But they wanted more.

Over the years, native-rights activists have fought for the repatriation of cultural artifacts removed without permission from sacred ancestral grounds by scientists and souvenir hunters. So at an emotional ceremony in the same CapeFox village the Elder visited on its way back to Seattle, Litwin and his colleagues presented to a delegation of Tlingit people four totem poles and more than a dozen other items taken from their village in 1899. “It was not just objects but actual ancestors [who] were coming back,” said anthropologist Rosita Worl, a Tlingit and expedition member, after the ceremony. “I could feel the happiness and relief of the spirits.” Litwin agreed. “It’s taken a hundred years to sort through this issue,” he said. “Today that circle’s been closed.”

What, in the end, did Harriman Retraced teach those who went along for the ride? “We learned how to start asking the right questions,” Litwin said recently in his office at Smith’s ClarkScienceCenter, where he was editing a book about the trip. (The Harriman Expedition Retraced, A Century of Change will be published by Rutgers University Press in 2004.) “We saw in Alaska if you stop overexploiting individual species, they’ll come back. But what if you’re destabilizing an entire ecosystem like the Bering Sea or the Tongass rain forest? Will it come back?” Another question Harriman Retraced taught Litwin to ask is why, in light of what happened in Alaska over the past century, do we continue to treat ecosystems that are essential to our survival in unsustainable ways? “And if the answer is because somebody is making a lot of money, then we have to ask ourselves and our policy makers one final question: Is that a good enough answer?”