Nothing Can Stop the Zebra

A 150-mile fence in the Kalahari Desert appeared to threaten Africa’s zebras, but now researchers can breathe a sigh of relief

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/zebras-Makgadikgadi-Pans-National-Park-631.jpg)

James Bradley pirouettes slowly on the roof of his Land Rover. A 13-foot-long aluminum pole with an antenna on top is sticking out of a front pocket of his shorts. The radio in his hand crackles with static. Bradley makes three tight circles, sweeping the air with the antenna, until the radio finally beeps. “I’ve got her,” he says. “It’s Rainbow.”

Rainbow is one of an estimated 20,000 plains zebras that wander across Botswana’s Makgadikgadi Pans, a bleached expanse of grasslands and blinding white salt flats in the Kalahari Desert. She is also one of ten mares outfitted with a radio collar, providing Bradley with valuable insights into southern Africa’s last great migration.

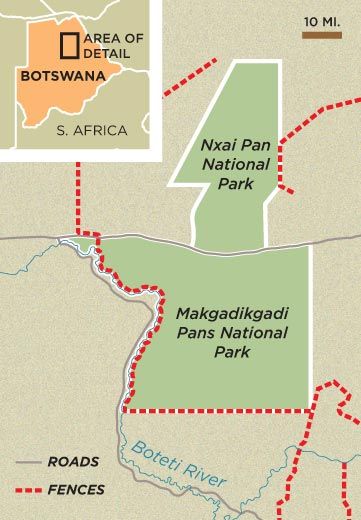

Bradley, 28, a tall, lean biologist from England’s University of Bristol, runs the Makgadikgadi Zebra Migration Research project, which was begun a decade ago to answer a critical question: Would an eight-foot-high electrified fence stretching 150 miles across the zebras’ territory disrupt their migration? The annual exodus, triggered by rains, is second only to the Serengeti’s in number of zebras. The project aims to understand the impact of fencing policies on wildlife not just here but, potentially, across Africa.

Much of wild Africa, contrary to its popular image, is in fact interrupted by fences and roads and enclosed within parks and preserves. But one of the continent’s largest intact ecosystems remains in northern Botswana, where poor soil and limited water have restricted human development. Formed by a string of national parks and protected areas, the wilderness zone covers some 33,000 square miles, an area larger than South Carolina.

The fence, which the Botswana government installed on the western edge of the Makgadikgadi Pans National Park in 2004, was primarily intended to protect cattle on neighboring rangelands from lions that live in the park. But wildlife experts became concerned about the barrier’s impact on zebras. They had reason to worry, given Botswana’s disastrous history with fences. In 1983, during a devastating drought, at least 50,000 wildebeest died in the central Kalahari because a fence blocked their route to water. It had been erected to prevent the spread of disease from wildlife to cattle.

But trying to predict how the new fence would affect the vast zebra herds that rely on that expanse of parkland was no easy task. Bradley’s predecessor, Christopher Brooks, who started the zebra research project and now works on a conservation project in Angola, Namibia and Botswana, was “concerned that a fence could have serious negative consequences,” he says, “but there was no solid ecological data” about the zebras and their migration.

Despite being among the most recognizable of large African animals, as well as a cousin of the domestic horse, zebras and their extraordinary movements turn out to be rather mysterious.

Zebras come in three distinct species: plains, mountain and Grévy’s; plains zebras are the most widespread, occurring throughout much of southern and eastern Africa. As members of the Equus genus, they are closely related to horses and wild asses. (Zebras aren’t well suited to domestication, however; they are unpredictable and have been known to attack people trying to handle them.)

During the dry season, zebras live along the Boteti River, the only regular source of water. When the rains come, in early summer, the herds move east to open grassland, where temporary pools fill with water, and then on to the rain-filled salt pans, where nutritious grasses grow on the periphery.

Bradley and I are driving some 25 miles east of the Boteti when we catch up with Rainbow. The first summer showers fell a week before, prompting 20,000 zebras to leave the river and file into these verdant pastures, trusting in puddles to sustain them on their journey to their wet season range alongside the salt pans. Rainbow is grazing with a few dozen others. Despite her name, she is as black and white as the next zebra. “She was named by a donor’s 6-year-old daughter,” Bradley says with a smile.

“Steady on, boys,” Bradley says as a scuffle breaks out in front of our moving truck. We stop and he decodes the quadruped drama: “The one on the left is the harem stallion. He’s shepherding a young female. Maybe she’s just come on heat and he’s aggressively protecting her from other stallions.” While the 50 or so zebras in front of us appear associated, Bradley explains that the only lasting social unit is the harem, made up of a lone stallion, one to six mares and their offspring. These small, tightknit families come together by the thousands for the seasonal pilgrimages in search of grass and water.

Like a human fingerprint, a zebra’s stripe pattern is unique. There are many theories about why the stripes evolved. The dizzying lines might distort a zebra’s outline, for instance, or make the animal look bigger, confusing predators. Take away their patterns, and the zebras before me look like small horses. Their gait, mannerisms and portly shape match those of their domesticated cousins.

Nomadic and gregarious, plains zebras are not at all territorial. But stallions do fight to protect mares in their harems or abduct mares in heat. (Bradley tracks mares rather than stallions because the females are less likely to fight with each other and damage the collars.) The ties that bind a stallion and his harem are profound. Bradley once noticed a lone stallion standing for hours in the riverbed, not eating. When Bradley approached, he saw that the stallion was standing vigil over a dead mare.

The young zoologist has witnessed this single-minded devotion when he’s darted mares to collar them. “Once the tranquilizers start to take effect, some stallions bite on the females’ necks to try to keep them upright and moving,” he says. “While we’re busy with the female, the stallion moves through the herd, constantly calling, looking for his missing mare. When she wakes up and calls, the stallion heads directly to her.” Mares, too, are loyal, often remaining with a single harem for life, a period that can span 16 years.

It’s midday, the temperature is 99 degrees and Bradley still has nine mares to locate. The GPS devices on the animals’ collars have an annoying habit of failing, forcing Bradley to rely on radio signals—and instinct—to find them. He then records their position, behavior and grazing preferences.

We pass the occasional oryx antelope and ostrich pair, and every few miles a korhaan, a rooster-size bird, tumbles from the sky in a courtship display. Bradley spends an increasing amount of time on the vehicle’s roof, using the slightest rise in elevation to pick up a signal. “Come on, zebras,” he sighs. “Where are you, my girls?” We drive some more. “They’re keeping themselves hidden,” he says.

We come to an area littered with dried zebra dung and scarred by deep game trails. The grass is brittle, stubby, overgrazed. “This is where the zebras grazed in the dry season,” says Bradley, fiddling with his GPS. “Let’s see...we’re 17 miles from the Boteti River as the crow flies.” I let the information sink in—these zebras undertook 34-mile round trips every two to four days to get from water to food, to water again, on an endless journey between thirst and hunger. Bradley has calculated that the zebras travel more than 2,300 miles a year.

By tracking the zebras’ movements, Brooks and Bradley have discovered that zebras are more resilient than previously thought. Some books claim that zebras drink daily and seldom stray more than seven miles from water. Yet the Makgadikgadi researchers recorded them trekking in dry months more than 22 miles to preferred grazing lands. During such trips, the animals go without water for up to seven days. At first, the researchers believed they were forced to travel so far in part because of grazing competition from cattle. But with cattle fenced out, the zebras continue to traipse record distances. “What drives them?” Bradley wonders aloud. “I’ve seen them walk past what looks like perfectly good grass to come out here.”

The Boteti River forms a natural boundary between the Makgadikgadi Pans National Park and nearby cattle-ranching villages, and provides a crucial lifeline during the dry season, when summer rains cease and grasslands wither, and zebras, impala antelope, wildebeest and other animals seek refuge and water along the riverbanks.

But in 1989, after years of drought, the Boteti dried up, evaporating into a necklace of small stagnant pools. Herds of cattle regularly trespassed miles into the park, overwhelming the tiny water holes, trampling and overgrazing the dusty surrounds. Crowded out from water and pressured to walk long distances in search of grazing, countless zebras perished.

When the seasonal summer rains began, the zebras migrated to rain-filled pans in the east to give birth, mate and fatten up on nutrient-rich grasses. With the zebras gone, lions near the Boteti strayed out of the reserve and feasted on cattle. And where lions killed cattle, ranchers killed lions. During the wet season of 2000, cattle farmers destroyed 8 of the park’s 39 lions.

Botswana’s Department of Wildlife and National Parks barricaded the park’s western boundary to keep wildlife and cattle apart: the fence went up along the river, crossing in places between the east and west banks and divvying up the remaining water holes between cattle on one side and zebras on the other. Yet in the dry season, too many animals competed for too little water. Elephants bullied zebras and wildebeest. Prowling lions set off terrifying stampedes of zebras.

In another attempt to protect wildlife during the drought, government authorities and lodge owners in 2007 dug holes and filled them with water from deep below the Boteti sand. “The zebra stood 20 yards away, watching us dig. When we pumped the first water, they were there in an instant,” says Bernie Esterhuyse, operations director of Leroo La Tau safari lodge. “I had tears in my eyes when I saw them finally drink in peace.”

And then in 2009, for the first time in 20 years, high rainfall in Angola, the river’s catchment area, sent a gentle flood down the parched riverbed, and the Boteti began to flow into the reserve again. Crocodiles emerged from dank riverbank caves, where they had holed up for years. The water released hippos from foul puddles full of waste that poisoned fish. And it brought back fish and frogs—and water birds that fed on them.

Thanks to the influx, zebras “no longer need to crowd around pumped water holes,” Bradley says. Now, in addition to studying the impact of the fence and other human interventions on the zebras, Bradley will monitor the animals’ long-term response to the return of the river.

It’s late afternoon when we hear the beep-beep radio signal of a collared mare named Seretse, which means “muddy” in the local Setswana. “She’d been rolling in the pans and was covered in mud when we collared her,” Bradley explains.

Cresting a low hill we’re treated to an extraordinary spectacle. Thousands of zebras upholster the valley below. Wave after wave of them kick up pink dust in the last flush of daylight. They are clustered in small pockets, most moving with their heads low to the ground, tearing through the grass with their teeth. Some stand in pairs resting their heads on each other’s shoulders; others nuzzle and groom their herd mates.

Suddenly three bull elephants stampede across the flanking hillside, trailing clouds of dust. Something has spooked them, and the zebras, too. The zebra herds begin to trot nervously away. Individuals call out “kwa-ha, kwa-ha” to stay in contact with one another. We can’t get close. Bradley decides to call it a day. We make camp in the valley and I fall asleep to the zebras’ haunting calls—until a jackal arrives, howling indignantly at my tent, apparently affronted by its appearance in his territory.

A fresh chorus of kwa-has greets the sunrise. “Yes, yes, we’re coming,” mutters Bradley as he folds his bedroll and we set off to find Seretse. “Zebra really are a keystone species in the Makgadikgadi,” he tells me as we bump along. As the vanguard of the migration, zebras chomp longer grasses, exposing short, sweet shoots for the more selective wildebeest that trail them, while the small population of springbok, bringing up the rear, must settle for leftovers. Then there are the predators zebras sustain. “Lions eat them and brown hyenas scavenge their carcasses,” Bradley says.

His words are barely out when we come upon a tangled heap of vultures. They peel away at our approach, revealing a half-eaten zebra foal. “I was worried I was going to look down and see a collar on it,” Bradley confides as he examines the carcass, taking hair samples and noting his observations: 1-month-old foal, emaciated, no sign of predation. “Natural causes,” he says, meaning anything from illness to starvation. A quick count reveals we’ve interrupted the meal of 44 vultures, four crows and a jackal.

We finally come upon Seretse. “She’s a beautiful zebra,” Bradley says fondly. And indeed she is—strong and fat and pregnant, with bolder stripes than the others. Soon we’re on a roll, locating three more mares. I calculate that we’ve seen roughly 4,000 zebras so far. So where are the other 16,000?

In spite of recent rains, there’s no standing water in the grasslands, and Bradley suspects the zebras may be heading back to the Boteti until more rain arrives. We drive to the river, and I see the fence cutting through it, running along the far shore. It’s no longer electrified and sections of it float, unhinged, in the water. There are few zebras, though; Bradley later finds most of the population east of where we had been tracking the collared animals, an indication of how unpredictable their movements can be. At the Boteti, fat cows graze brazenly against the fence.

Upstream, we meet a safari guide named Patrick Keromang. He tells us that three lions crossed the river the previous night, breached the fence and killed eight cows. One lion was shot dead by villagers.

I cross the Boteti with Keromang in an aluminum boat and then we drive along the fence. He points out where honey badgers have tunneled beneath it on their nightly rounds. This is where the lions escaped the reserve. Thorny branches plug the holes, a makeshift repair by villagers and lodge staff to render the fence less porous.

Ten years into the zebra-monitoring project, Bradley and his colleagues can report that the species is thriving. Early indications are that the Makgadikgadi fence does not restrict their migration, which is largely east of the river, and has actually had a positive impact on the park’s wildlife. “Shortly after the fence went up, the behavior of zebras changed rapidly, and they relaxed a little more,” Bradley told me. Farmers no longer chased the zebras away, and there was more water to go around. “Zebras were seen resting within the riverbed itself—something which didn’t happen before the fence.” Reduced competition from cattle has meant more grazing for zebras inside the park. More zebra foals are surviving beyond their first year, and the population appears to be growing.

“Fences have been generally viewed as a disaster for large migratory herbivores,” says Ken Ferguson of the University of Pretoria in South Africa, who specializes in studying the effects of fences on wildlife. But the zebra research project, contrary to expectations, “underlines the fact that not all fences need be ‘bad’ for conservation.” In fact, what he calls “responsible” fencing can benefit wildlife by keeping it in dedicated enclaves or preventing conflicts with humans.

Bradley can’t say for sure whether the zebras are benefiting from the fence, the return of the river, the recent higher rainfall or some combination of all three, but he says the health of the population means that, “given the chance, animals will often be able to respond to cycles of good and bad years and bounce back.”

That evening, overlooking the river, Keromang tells me that just the week before, processions of zebras were overrunning the banks, arriving at midday and drinking into the night. It was a noisy affair, the air thick with their whooping, barking calls. Less than an inch of rain was all it took for distant water holes to fill up and the herds to vanish overnight. The sandy, rain-pocked shores are silent now. And empty. Except for the faint scrawl of zebra tracks meandering up the bank and into the grasslands beyond.

Robyn Keene-Young and her husband, photographer Adrian Bailey, have spent the past 15 years documenting African wildlife. They are based in South Africa.