Now You Can Genetically Test Your Child For Disease Risks. Should You?

Genomics is cheaper and more available then ever, but its usefulness for parents has yet to be proven

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/2d/24/2d24b6d6-ad25-40da-bafb-0e8322a38b43/f025kr.jpg)

Before Cheryl Connolly gave birth to her first child, Loudon, she ran through the checklist of all the things expecting parents are supposed to do these days:

1. Create a birth plan.

2. Consent to the newborn heel prick test for metabolic diseases.

3. Bank his umbilical cord blood.

But now, she learned, there was a new one to consider: Sequence his DNA.

Connolly knew of an ongoing genomics research study called MyCode, which would make it possible for his doctor to take a sample from Loudon's umbilical cord and send it to a lab that would look for mutations in his genetic code. Run by the Geisinger healthcare system in central Pennsylvania, where she worked as a fundraiser, the genetic test would evaluate his likelihood of developing a myriad of disorders that can occur in childhood—from abnormal heart conditions to cystic fibrosis to high cholesterol.

Neither Connolly nor her husband, Travis Tisinger, had a history of childhood diseases in their families or were aware of any hereditary conditions they might pass down. But when she learned that the program was expanding to her hometown, the couple decided to undergo testing, which for them would mean a blood test and swabbing saliva. Then a colleague suggested that they test Loudon as well. For them, the decision was simple.

“You hear about kids on ball fields dying of heart conditions that could have been prevented,” says Connolly, who was seven months pregnant at the time. “Why wouldn’t you want to know about as many of these things as you could?”

Well, it isn't quite that simple. On the one hand, you might learn valuable information—like whether your child has the gene for dangerously high cholesterol, a treatable condition called familial hypercholesterolemia that affects as many as one in 250 people and increases the risk of early heart disease by a factor of 20 according to the FH Foundation. That could prompt you to start your child on a low-fat diet or ask your pediatrician about statin therapy. Currently, the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG) has named 56 genes for variants that “would result in a high likelihood of severe disease that is preventable if identified before symptoms occur.”

(Many women already engage in some level of genetic screening before the baby is born. In addition to a first-trimester ultrasound, an increasingly routine blood test analyzes DNA from the mother and fetus to detect some chromosomal abnormalities, including Down syndrome at 10 weeks. But the test is limited in scope, and there’s a higher risk of false positives with younger women.)

On the other hand, you could also discover something terrifying that you’re helpless to prevent. A growing number of labs and apps will reveal a child’s potential to develop certain cancers or incurable diseases, such as Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s, that wouldn't appear until your child was grown—if at all. The potential medical, psychological and social implications of this uncharted territory has prompted the American Academy of Pediatrics and ACMG to oppose genetic testing for adult-onset conditions “unless an intervention initiated in childhood may reduce morbidity or mortality.”

Advances in genomics now give parents the opportunity to peer into their children’s genetic futures in ways they might never have imagined. Now the question is: do they need to know everything?

“When we’re talking about fishing around for genetic disorders in healthy kids, we get into the weeds unless we can offer something that’s medically actionable now to reduce the risk later on,” says Naomi Laventhal, a neonatal physician and bioethicist at the University of Michigan’s Center for Bioethics and Social Sciences in Medicine. “The big question is, how much do we want to know—and what can this information really tell us.”

New Questions

As the youngest patient ever to take part in MyCode, Loudon is on the forefront of a new trend. Since Geisinger started accepting children into their study in 2012, minors have made up 2 to 3 percent of patients. Geisinger has enrolled more than 180,000 people in partnership with pharmaceutical company Regeneron since the study began in 2007.

Most direct-to-consumer genetic testing services still require that patients be at least 18 years old. But there are workarounds. The popular at-home DNA test 23andMe requires that users be 18, but parents can order $199 kits for their offspring and send back their saliva through the mail, according to spokesman Andy Kill. (Kill says the company doesn't have statistics on how many children’s samples it has received.) And in April, the FDA ruled that 23andMe could release reports about patients’ risks for diseases, including Parkinson’s and late-onset Alzheimer’s diseases.

As testing children for genetic diseases becomes available to more parents, it is raising difficult ethical questions. For instance: Would the knowledge that your kid might get sick someday make you treat them differently? “There’s a concern that parents might connect to kids in a different way if they knew something negative about their future,” says Laventhal. Perhaps you'd be proactive by pushing your daughters to freeze their eggs at a young age, if you knew they were at risk for cancers and might undergo cancer treatments that could hurt their fertility.

“You’re going to create a lot of unnecessary stress and anxiety and make parents crazy,” adds Dr. Lainie Friedman Ross, who researches genetic testing policy at the MacLean Center for Clinical Medical Ethics at the University of Chicago. “You’re going to have a generation of helicopter parents who are trying to control every aspect of their kids’ lives.”

Loudon's parents, at least, won't have to wrestle with the question of what to do if their son is at risk for an incurable disease. The Geisinger program that sequenced his DNA will only inform them of risks to his health that can be managed or prevented during childhood. In addition, researchers haven’t yet started returning pediatric results.

“You’re so afraid you’re going to find out your kid will be sick in 20 different ways, and there’s nothing you can do about it,” says Loudon’s father, Travis Tisinger. “I wouldn’t even want to know about my son’s risk for things like Parkinson’s or Alzheimer’s. Raising him has been the best two years of our lives. He’s young and vibrant and healthy. That’s the only way I want to see him now.”

A Crystal Ball?

Adults aren’t even sure what to make of this new windfall of potentially upsetting information about themselves. Headlines are rife with tales of DNA tests uncovering family paternity secrets or cracking open family trees. As for health bombshells, the recent holiday ad campaigns to gift genetic tests to relatives are forcing people to realize a whole new set of family dynamics: If your mother learns she has the genetic variant for Alzheimer’s, that means you might have it, too.

At first, bioethicists were worried about overachieving parents believing the claims of companies that offered to unlock the secrets of their children’s ability to spike a volleyball or sprint down a soccer field. In 2015, a group of international sports medicine experts warned about defining kids by their DNA through so-called “talent identification” testing. They argued that not only is there a lack of scientific consensus about which genes are responsible for which abilities, but different companies came to dramatically different conclusions about the same person.

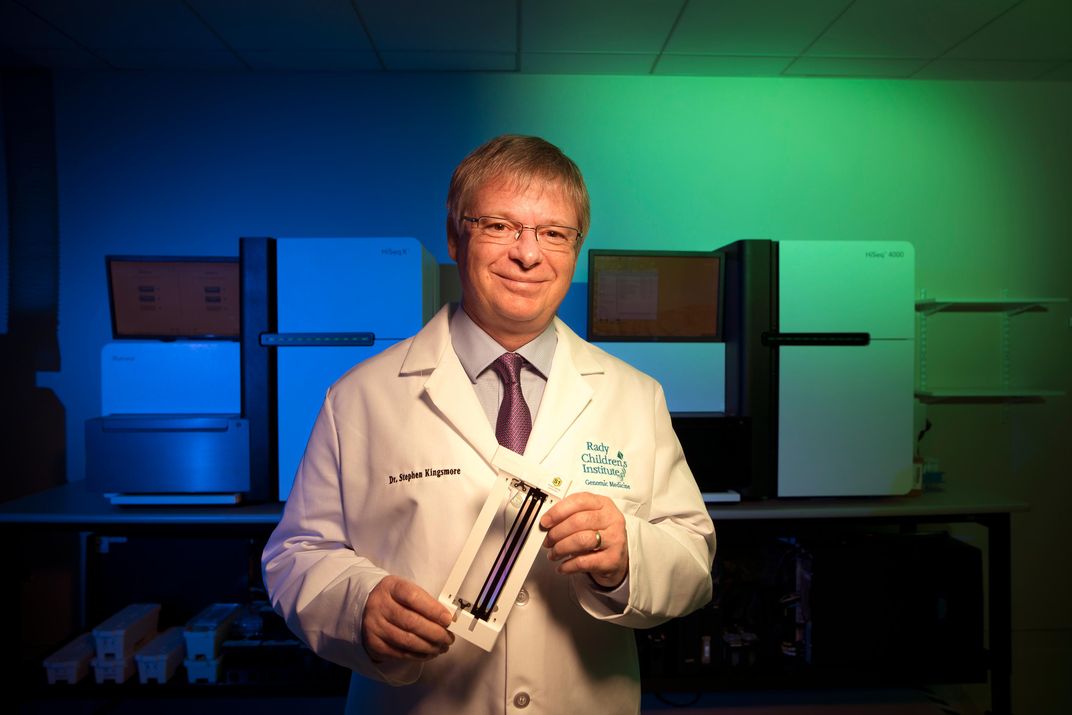

But the genomics science of diagnosing sick children for rare diseases has improved dramatically over the last five years. Next-generation sequencing technology has enabled testing for thousands of rare diseases at once, and shortened turnaround times from as long as six months to several days. In 2016, Dr. Stephen Kingsmore, founder of the Rady Children’s Institute for Genomic Medicine in San Diego, won the Guinness world record for fastest sequencing time at 26 hours. And the National Institutes of Health has since 2013 funded four newborn sequencing pilot programs, including Rady’s, around the country.

So far, the cost of testing your children is prohibitive for many families: it generally falls between $5,000 and $10,000 for healthy children and their biological parents. (Testing both parents and child is the gold standard, since their DNA offers clues and context to the child’s code.) But the price might soon be within reach for millions more patients: Last year, genomics giant Illumina announced new technology that it hoped would bring down the cost to $100 per entire patient genome in a few years. (The price of analyzing those results will take longer to come down.) Moreover, several private insurers announced last year they would cover large-scale sequencing for sick children.

Dr. Brandon Colby, a medical geneticist who promotes “genetically-tailored wellness plans” for children from newborns to teenagers, thinks consumers should adopt a broader view of disease prevention and recognize that it starts at birth. He has a dog in this fight: he’s the founder of Sequencing.com, a marketplace of apps that crunch DNA data from testing services and offer health insights. He’s also the author of the 2011 book Outsmart Your Genes, which advocates for widespread childhood testing.

His most popular apps with parents are those that look at a variety of health conditions, such as a child’s risk for several cancers, heart disease, vitamin deficiencies as well as predictions for body mass index, lactose intolerance, hair loss and whether he or she is more likely to succeed in endurance or strength sports. And this year, his company plans to release two new genetic testing apps that reveal one’s Alzheimer’s risk and include prevention tips.

Colby sees a world in which parents who knew their children had a gene for melanoma would be more vigilant about applying sunscreen or taking them to the dermatologist. You’d avoid exposing your children to unnecessary radiation if they were predisposed to breast cancer and forgo contact sports, if you worried that that childhood head trauma would increase their risk for Alzheimer’s disease later in life. You’d find a way to sneak brussels sprouts into their lunch boxes, if you knew that they had one of the genotypes for which cruciferous vegetables lessened the risk of heart disease, he says.

“While ‘adult-onset’ diseases are diagnosed as adults, for almost all of chronic diseases the damage to the body starts decades earlier,” says Colby.

Unintended Consequences

Yet experts aren’t convinced that the potential usefulness of such information is worth saddling a child with an unwanted medical identity—and their parents with unnecessary angst. “It’s grandiose to think we can prevent adult-onset cancer by changing how we raise our kids," says Ross. "There’s so much more we need to learn.” And don’t good parents make their kids eat broccoli, wear sunscreen and avoid head injuries anyway?

From a child's perspective, imagine the emotional toll of going through puberty if you knew you had the gene for breast cancer or being the “melanoma kid” on your soccer team. What kind of teasing could kids expect to endure in junior high if their classmates knew they were at risk for Alzheimer’s? “Not every child has the maturity to understand what things mean, and that could be an unfair burden on a kid whose whole life is ahead of him,” says Laventhal.

It’s too early to tell how these scenarios might play out, but one study offers some clues. University of Michigan cancer genetics researcher Michelle Gornick led a team that asked 66 people about their views on receiving troubling information about potential adult-onset genetic disorders after their children were screened for other conditions. After hearing presentations from geneticists, 44 percent supported policies that prevented access to their children’s results, while more than half stood up for parents’ rights to know.

In a follow-up study published last spring in the Journal of Genetic Counseling, those who favored restriction said children had the right to make their own choices when they became adults. One participant imagined her two children having different reactions, saying: “One kid would be like, ‘Yeah, I want to get tested to see if I have the Alzheimer’s thing.’ The other one would be like, ‘No, don’t tell me.’ So part of me is wondering ‘Do I have the right to make that decision for my sons or daughters when they might have wanted the other alternative if they were older?’”

.....

Several participants also voiced the concern that’s becoming increasingly urgent: How could my results affect me (or my kids) financially? Although the 2008 Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act protects Americans from being denied health insurance or jobs because of what’s lurking in their DNA, it doesn’t include life, disability or long-term care insurance.

In the meantime, all this chatter about what we should and shouldn’t know is missing an important point: The actual science might not be ready to tell us the right information, says Timothy Caulfield, research director of the University of Alberta’s Health Law Institute. Geneticists are still researching how the discoveries of many single gene variants interact with a person’s environment, family history and microbiome to better predict a person’s risk for many diseases.

“The reality is that if you have a generally healthy kid, there aren’t a lot of specific interventions that you can do,” says Caulfield. “For most risks, it comes back to the same things: Exercise. Eat well. Wear sunblock. Get a good night’s sleep. You don’t need genetic tests to tell you that.”