Nurture, Not Nature: Whooping Cranes Learn to Migrate From Their Elders

New research shows that the endangered cranes learn to navigate thousands of miles by taking cues from older birds

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20130829011136crane-2-copy.jpg)

The Eastern U.S. is home to exactly one population of wild whooping cranes. Each fall, members of the flock migrate more than 3,000 miles, from Alberta, Canada, to the Gulf Coast of Texas. But these enormous, long-lived birds (they can stand up to five feet tall and live as long as 30 years) are endangered, with only about 250 left in the wild.

The Whooping Crane Eastern Partnership is trying to change that. Since 2001, the group has bred cranes at the Patuxent Wildlife Research Refuge in Maryland, brought them to the Necedah National Wildlife Refuge in Wisconsin for nesting, then guided young cranes down to Chassahowitzka National Wildlife Refuge in Florida for the winter with an ultralight aircraft, just like the technique used in the movie Fly Away Home.

After their first migration, the cranes are left to their own devices and are forced to make the trip on their own every year. But to ensure their survival, researchers carefully track and log the precise routes they take each year, using radio transmitters attached to the birds.

New research shows that the endangered cranes learn to navigate thousands of miles by taking cues from older birds. Image by Heather Ray/copyright Operation Migration USA Inc.

For Thomas Mueller, a University of Maryland biologist who studies animal migration patterns, eight years of records collected as part of this project were an especially appealing set of data. “The data allowed us to track migration over the course of individual animal’s lifetimes, and see how it changed over time,” he said.

When he and colleagues analyzed the data, they found something surprising. As they write in an article published today in Science, the whooping cranes’ skill in navigating a direct route between Wisconsin and Florida is entirely predicated on one factor: the wisdom of their elders.

“How well a group of cranes does as a whole, in terms of migrating most effectively and not veering off route, really depends on the oldest bird in the group, the one with the most experience,” Mueller says. The years of data showed that, as each bird aged, it got better and better at navigating, and that young birds clearly relied heavily on the guidance of elders—the presence of just a single eight-year-old adult in a group led to 38 percent less deviation from the shortest possible route between Wisconsin and Florida, compared to a group made up solely of one-year-olds. Mueller’s team speculates this is because as the birds age, they grow more adept at spotting landmarks to ensure that they’re on the right path.

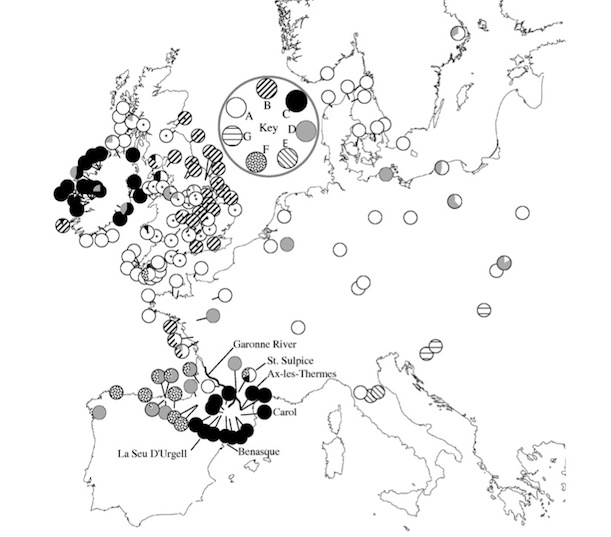

The data (left) showed that groups consisting solely of one-year-olds (dark red dots) often veered far off course, while groups with older birds (green dots) tracked a straighter path. The right map shows average migrations (dots) for groups with a four-year-old (blue) and one-year-old (red) compared with the direct route (straight line). Points marked with x show where birds began their migration; crosses show where birds landed. Image via Science/Mueller et. al.

The data also indicate that the flocks are prone to following one particular elder in any given migration, because total group size didn’t correlate with shorter trips. In other words, it’s not the overall migratory skill of the group as a whole that determines the flock’s route, but the expertise of one key elder crane that does so.

For Mueller, this finding helps to answer a question that researchers have been asking for years: Is the ability to migrate thousands of miles genetic, or learned? The research, which didn’t investigate genetics specifically, nonetheless gives credence to the latter.”This is really social learning from other birds, over the course of years,” he says. At the same time, he notes that “there’s also an innate component to it, because after they’re taught the migration once, the birds initiate it on their own every spring.”

These findings could have important implications for the conservation efforts. For one, they vindicate the current model of teaching young birds how to migrate once with an ultralight aircraft, because at this point, there are so few older birds in the breeding flock that can perform their natural role as migratory leaders. By letting the birds migrate on their own afterwards, though, the program allows them to learn from elders and develop their navigation skills.

The work could also provide hope for one of the crane program’s biggest challenges: getting the birds to breed on their own in the wild. Thus far, very few of the human-reared birds have successfully bred on their own after maturation. But if navigation is a skill that’s developed slowly over time, as the birds learn from others, it’s possible that breeding could operate the same way too. As the flock’s population ages as a whole and features a larger proportion of elder birds, the researchers say, they could gradually get more adept at breeding and pass those skills on to others.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/joseph-stromberg-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/joseph-stromberg-240.jpg)