Obvious But True: Full Moons Do Not Drive People Crazy

Another study debunks the idea that the lunar cycle triggers mental instability

![]()

Another study debunks the idea that the lunar cycle triggers mental instability. Image via Flickr user Fields of View

Some beliefs are so engrained that they live on in popular culture despite a total lack of evidence backing them up. Take, for instance, the idea that a full moon can trigger mass hysteria or psychosis.

Popularized long ago in werewolf mythology and other folklore, the myth persists to the degree that, according to one study, 64 percent of doctors and 80 percent of nurses still think it’s true—even though we’ve yet to see a plausible mechanism suggested for how moons could affect moods.

For these holdouts, a study published this week in General Hospital Psychiatry should finally put an end to it: In examining three years worth of records from a pair of Montreal hospitals’ emergency rooms, a group of researchers from Université Laval in Quebec City found that there was no connection between phases of the moon and psychological problems.

“We hope our results will encourage health professionals to put that idea to rest,” said Genevieve Belleville, the study’s lead author, in a statement. “Otherwise, this misperception could, on the one hand, color their judgment during the full moon phase; or, on the other hand, make them less attentive to psychological problems that surface during the remainder of the month.”

To test whether the lunar phases played a role in altering the incidence of psychological problems, the researchers looked specifically at 771 cases in which people showed up to one of the hospitals complaining of chest pains without an apparent underlying medical problem. After routine psychological evaluations, many of these individuals were diagnosed as suffering from anxiety, panic attacks, mood disorders or other psychological afflictions.

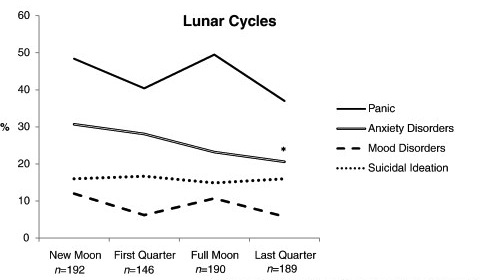

The researchers found no correlation between full moons and people entering the hospital with psychological problems. Image via Belleville et. al.

Charting the distribution of these cases across the four lunar phases—a new moon, a first quarter moon, a full moon and a last quarter moon—they found no statistically significant correlation between a full moon and people entering the hospitals with psychological problems. The researchers did find a slightly reduced incidence of anxiety disorders during the last quarter, a phenomenon they regard as either a coincidence or a result of overlooked factors.

This study jives with a body of research that has debunked the link between full moons and epileptic seizures, homicides, suicides, admissions to psychiatric institutions, calls to crisis centers, traffic accidents and countless other indications of erratic or unusual behavior. Meta-analyses have confirmed the lack of evidence for a positive association and suggested that the small number of studies that have turned up a positive correlation are the result of statistical errors.

Why, if this is the case, do so many people continue to believe that a full moon can cause madness? Part of the explanation is our natural tendency to see correlations between unrelated factors when none exist. If we already believe in a full moon effect, it also affects what we remember and reflect upon, a phenomenon called confirmation bias: The rare instance in which a person acted strangely during a full moon becomes far more memorable than the hundreds of full moons that pass without anything remarkable happening. Additionally, occasional newspaper articles that cite police officers saying they notice an uptick in crime during full moons perpetuate the belief.

So on November 28th, when the next full moon comes around, rest assured that it can’t drive you mad—and help put the superstition to bed once and for all.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/joseph-stromberg-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/joseph-stromberg-240.jpg)