Oldest Human Fossil Unearthed in Ethiopia

At about 2.8 million years old, the Ledi jaw may belong to “the stem for the Homo genus,” according to its discoverers

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/c5/a4/c5a46002-260c-470c-9df7-79bc0d3c5129/villmoare2hr.jpg)

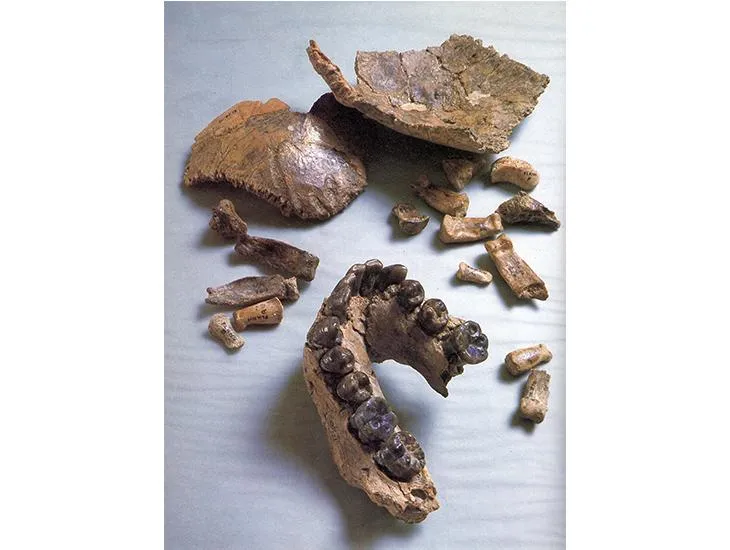

One January morning in 2013, while climbing an eroded hill in Ethiopia’s Afar region, Calachew Seeyoum came across a broken tooth. The graduate student knew at once that it was a fossil, and it was important. The thick enamel was a surefire sign that the premolar had come from one of our extinct hominid relatives. Squatting in the silty soil, Seeyoum found more teeth and half a lower jaw that confirmed his first impression.

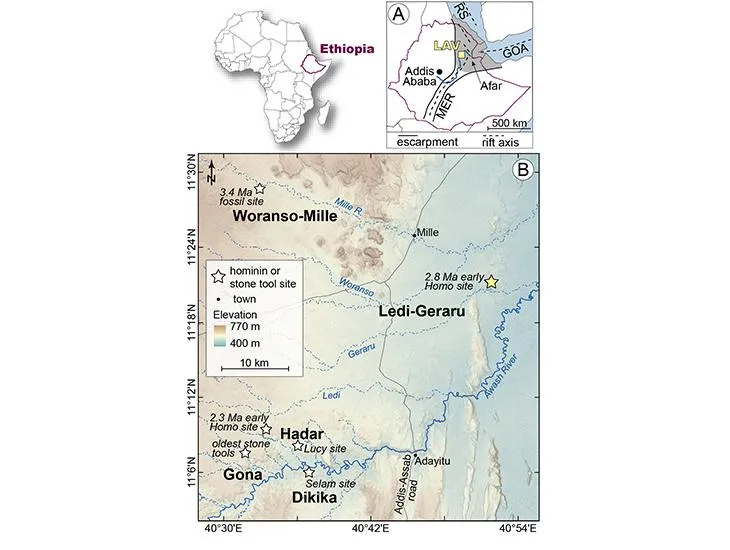

Plenty of hominid remains have been unearthed in the scorched land of Afar, including the first Australopithecus afarensis ever discovered, nicknamed Lucy. What made this particular outcrop at the Ledi-Geraru site special was its age. Layers of volcanic ash beneath the surface, dated by the reliable decay of natural radioactive crystals in the ash, put the mandible at between 2.75 and 2.80 million years old—neatly in between the last of Lucy’s apelike kin and the first-known example of our own genus, Homo.

After examining the Ledi jaw closely, a team of researchers has now declared its original owner to be the oldest bona fide human ever found. Predating the previous oldest fossil by more than 400 millennia, the specimen pushes back the origins of our family tree.

“We can’t say for sure, but we think this is probably the stem for the Homo genus,” says Brian Villmoare, a paleoanthropologist at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, whose team reports the finding this week in the journal Science.

Consistent with its early age, the jaw blends primitive and modern features. Its curve, the shape of the teeth and the arrangements of their cusps are all characteristically human. But the chin is decidedly not; it slopes backward, like that of an ape. “The anatomical characteristics are a very interesting mix that looks back toward Lucy and forward to more advanced species of Homo,” says study co-author William Kimbel, a paleoanthropologist at Arizona State University.

Positioned as it is in the fossil record, the find helps to fill in a chapter in human evolution that has long been relatively blank. Before about 3 million years ago, our hominid relatives bore a strong resemblance to apes. After about 2 million years ago, they look much more like modern humans. What happened in the middle is poorly understood, and only a handful of fossils from this time period have so far turned up.

Further excavations at Ledi-Geraru provided clues as to what might have driven this transition. Sandy sediments and the fossilized remains of animals indicate that the climate in the area started to shift as early as about 2.8 million years ago.

“We know that habitats in the Afar region at that time period were more arid than at older sites,” says Erin DiMaggio, a geologist at Penn State University and a member of a team publishing a second paper in Science. Drier conditions could have posed a challenge for more apelike creatures adapted for climbing trees, spurring our ancestors to start walking upright and change their diets in the burgeoning savanna.

For paleontologist Fred Spoor, the Ledi jaw announcement couldn’t have come at a better time. He too has recently come to the conclusion that the roots of humankind must run deep, after taking a fresh look at another jawbone discovered more than half a century ago.

This fossil of a young male was found in Tanzania in 1960 by Jonathan Leakey, grandson of famed fossil-hunters Louis and Mary Leakey. Back then it was commonly believed that the human family tree was a simple line: Australopithecus gave way to Homo erectus, and this “upright man” evolved into Neanderthals, which paved the way for our species, Homo sapiens.

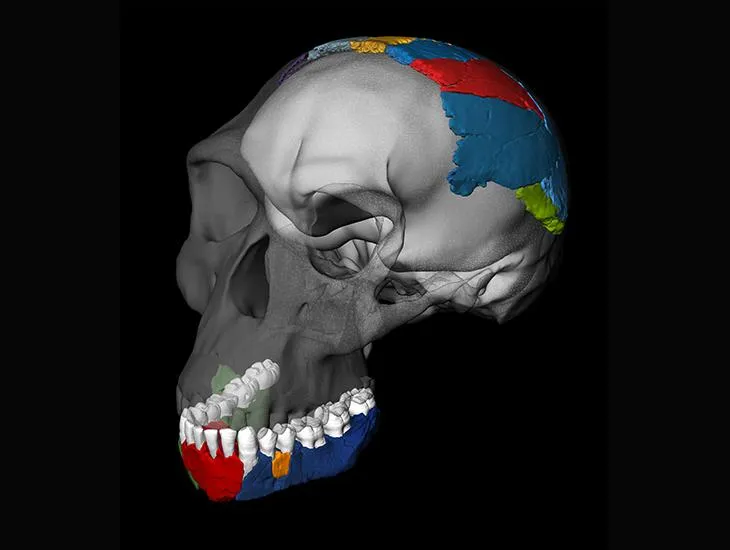

Johnny’s Child, as the 1.8-million-year-old remains came to be known, complicated things. Skull fragments found nearby indicated a brain bigger than that of Australopithecus, while finger bones suggested a hand that could grasp and use tools. Controversy erupted when the fossil was assigned to a new human species: Homo habilis, the “handy man.”

Today the debate continues over exactly how many species of early human walked the Earth. Most researchers split our early Homo relatives into at least two lineages that overlapped in time, H. habilis and H. erectus. Some add a third species with big teeth, known as H. rudolfensis. Not everyone agrees. In 2013 paleontologists measuring fossil skulls in the country of Georgia argued that all early humans belonged to a single species with lots of variety.

In search of evidence, Spoor decided to take a second look at Johnny’s Child. Though it is the poster child for H. habilis, the fossil is badly damaged. Cracks formed during the fossilization process, distorting its shape and complicating comparisons with other fossils. Unable to physically take apart the specimen and put it back together, Spoor’s team bombarded it with X-rays from a CT scanner and built a 3D model in a computer. Manipulating this model, the researchers virtually extracted the bits of fossilized bones from the rock in which they were embedded.

When reassembled, the virtual jaw and skull provided a clearer portrait of H. habilis. Comparisons between other fossils and this new standard strengthen the case for three distinct Homo species, Spoor and his colleagues argue in this week's issue of the journal Nature.

Even as it confirmed the traditional view, the digital upgrade surprised the researchers by shooting down what was thought to be a potential ancestor for H. habilis: a 2.33-million-year-old upper jaw reported in 1997 by Arizona State's Kimbel and colleagues. Though more than half a million years older than Johnny’s Child, this jaw has a shape more similar to that of modern humans, signaling to Spoor that it must belong to a different branch of the family tree, although which one is an open question.

“It’s more evolved, so it’s an unlikely ancestor,” says Spoor, based at University College London. “The lineage of Homo habilis has to go back further.”

The older Ledi jaw, with its more primitive features, could be a newfound ancestor of H. habilis, a branch on the lineage of the 1997 jaw—or perhaps both. But Kimbel and his colleagues have been careful not to assign the latest fossil to a species or tie it to a particular lineage just yet. It is, after all, only a single jawbone, and half of one at that.

“The Ledi jaw will be an iconic fossil, because it tells us that the evolutionary group to which we belong goes back that far,” says Rick Potts, director of the Smithsonian’s Human Origins Program and curator of anthropology at the National Museum of Natural History. “But it does not answer a lot of the questions that we would like to know.”