Why Panda Sex Isn’t Black and White

Reproductive experts weigh in on panda porn, panda Viagra and other biological myths

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/5f/50/5f50c7af-9586-4b42-b387-48ef56a5b098/a329a0.jpg)

Heini Hediger, the father of modern zoology, once declared that there was only one way for a zookeeper to measure his success: If the animals under his care produced more of their kind.

“To the zoo biologist this is like arithmetical proof to the mathematician,” wrote the Swiss biologist in Wild Animals in Captivity, a compilation of what he learned as director of the Basel Zoological Gardens, in 1942. “When breeding does not occur, something is wrong with the methods of keeping the animals; if breeding does occur, it is a guarantee that the conditions are essentially right.”

While zookeepers no longer consider successful reproduction the sole “proof” of good animal care, they still go to great lengths to persuade animals to make babies. For the giant panda—an ecologically threatened, beloved-by-humans and particularly well-researched species—those lengths can sound rather extreme. Reports of panda porn, panda Viagra and other provocative techniques for captive pandas abound.

But don’t believe everything you hear. This Valentine’s Day, Smithsonian.com polled readers on Twitter for some of the most prevalent myths about these charismatic creatures' love lives. Then we put them to panda reproduction experts from around the country to set the scientific record straight.

Is it true that giant pandas don’t know how to have sex?

Giant pandas are among the oldest of bear species, having lumbered the Earth for around 3 million years. In other words, they know how to do the deed. “If they have appropriate habitats, they do breed,” says Rebecca Snyder, curator of conservation and science at the Oklahoma City Zoological Park and Botanical Garden. And yet in the U.S., just one panda couple—Gao Gao and Bai Yun at the San Diego Zoo—has successfully bred using the natural method. So what’s the problem? “It’s our fault,” says Snyder. “We’re not doing something right.”

In the wild, pandas meet many potential mating partners and often mate with several. “So even if one male isn’t really good at natural breeding, it’s ok, because the female’s going to be bred by another male,” says Pierre Comizzoli, a staff scientist and reproductive physiologist at the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute. Comizzoli oversees the breeding protocols for Mei Xiang and Tian Tian, the 18-year-old female and 20-year-old male at the National Zoo.

In captivity, you usually have just one male and one female. Historically, zoos chose these pairs based not on behavioral compatibility but on their genes: The goal is to optimize genetic diversity among the captive panda population, and thus avoid creating a population of animals that are all closely related. It's also to ensure that pandas that are eventually returned to the bamboo forests of China have a fighting chance.

But genetically based matching doesn’t always bode well for panda romance, says Meghan Martin, a conservation biologist and director of the nonprofit PDX Wildlife. In 2013, Martin and colleagues published a study showing that pandas paired with pandas that they liked tended to mate more, and have more babies. Which makes sense: “Imagine you being told, ‘Hey, this male is genetically not related to you, so you guys would make great babies. Here, go in a room, have babies, and let us know how that goes,’” says Martin.

Thanks to the steady growth of the captive panda population in the past decade, U.S. zoos are now able to offer their pandas at least some choice in the matter. For some zoos, the next step might be a panda-matching app: Martin's latest research shows that panda attraction could benefit from matching up complementary personality traits (i.e. aggression, excitability, fearfulness). Now, a Dutch zoo has started letting its female orangutans choose the most appealing mates from images on a Tablet, in a four-year experiment it has called “Tinder for orangutans.”

Who knows? It might be just a matter of time before we have BambooSwipe.

Do panda breeders really use panda porn to get them in the mood?

The three panda experts I spoke with each gave a resounding no. “No, no, never,” said Comizzoli. “It’s ridiculous,” said Snyder. “I have been actively doing research in breeding season over the past seven years, and I’ve never seen it,” said Martin, who travels each year to China’s Bifengxia Panda Center, one of the largest breeding centers in the world, and called me while on the road to a wildlife conference in Oregon. (Apparently she gets this question a lot: “Is she asking about the porn?” her husband asked from the front seat.)

Yet just because it isn’t used in the U.S.—Martin says she can’t speak to rumors that “porn” has been used at places like China’s Chengdu Research Base—doesn’t mean pandas couldn’t use some enhancement in the marital den. The problem is, even the most high-quality panda porn videos wouldn’t do much for these bears, because they don’t seem to have very good eyesight, Comizzoli says. A better idea would be using scent or audio. Researchers could play tapes of pandas bleating, he says, or spray the scent of urine and excretions females make from their pre-breeding scent glands.

As for giving a panda Viagra? Dream on. Aside from the fact that the human drug has not been shown to have any effect on bears, Comizzoli reminds us that Viagra typically works by increasing blood flow to the penis. “Viagra is not a sexual enhancer,” he says. “It’s just for the male to have an erection, but then after that he still needs to know how to use it.”

Are any animals harder to breed than giant pandas?

It’s true that panda sex isn’t exactly black and white. But experts say the notion that they are the most challenging animals to mate in captivity is patently unfair.

“It’s complicated. It’s specialized. It requires a lot of attention,” says Comizzoli. “But I would say this is not the only species like this.” Captive female elephants, for instance, are notorious for their infertility problems, and males can be lethally aggressive. And don’t even get Comizzoli started on cheetahs, which he has also researched extensively: “You need a real chemistry between both individuals, and sometimes it’s really difficult to recreate that in captivity,” he says.

By contrast, the signature challenge in breeding pandas is the absurdly short period of time that females are receptive to mating. Lasting a maximum of two days and sometimes as short as 36 hours, the window of opportunity is narrow. Equally frustrating, zoo keepers and staff never know when this elusive window will occur—and if they miss it, they’re out of luck until next spring. That’s why Comizzoli avoids traveling between the months of March and May, so as not to risk missing Mei Xiang’s special time.

Panda breeders have devised a number of methods to figure out when that window is occurring. First, they measure hormones in panda urine. They also look out for telltale signs: Typically, the female advertises her readiness by rubbing sexy secretions from her anal glands onto tree trunks, rocks, or on the ground. Then, she’ll call the male over by chirping or bleating like a sheep, says Comizzoli. (If she doesn’t like that particular male, “she’ll do this moaning sound that sounds like Chewbacca,” adds Martin.)

Finally, she walks backwards and pump her tail up and down in a way that Comizzoli describes as “a little bit like a Michael Jackson moonwalk.” “The male is really interested in the female at this point,” he adds.

A moonwalking panda? I’d be pretty interested too.

Is it impossible to tell when a panda is pregnant?

At the moment, it’s really hard. Part of the reason is that pandas have peculiar pregnancies. Most mammals—including humans—experience a surge of the hormones estrogen and progesterone when their bodies are preparing for a pregnancy. These hormones can be measured in feces, blood or urine (a human pregnancy stick works by measuring levels of these hormones in the latter). Pandas, however, experience this surge every year whether they’re pregnant or not.

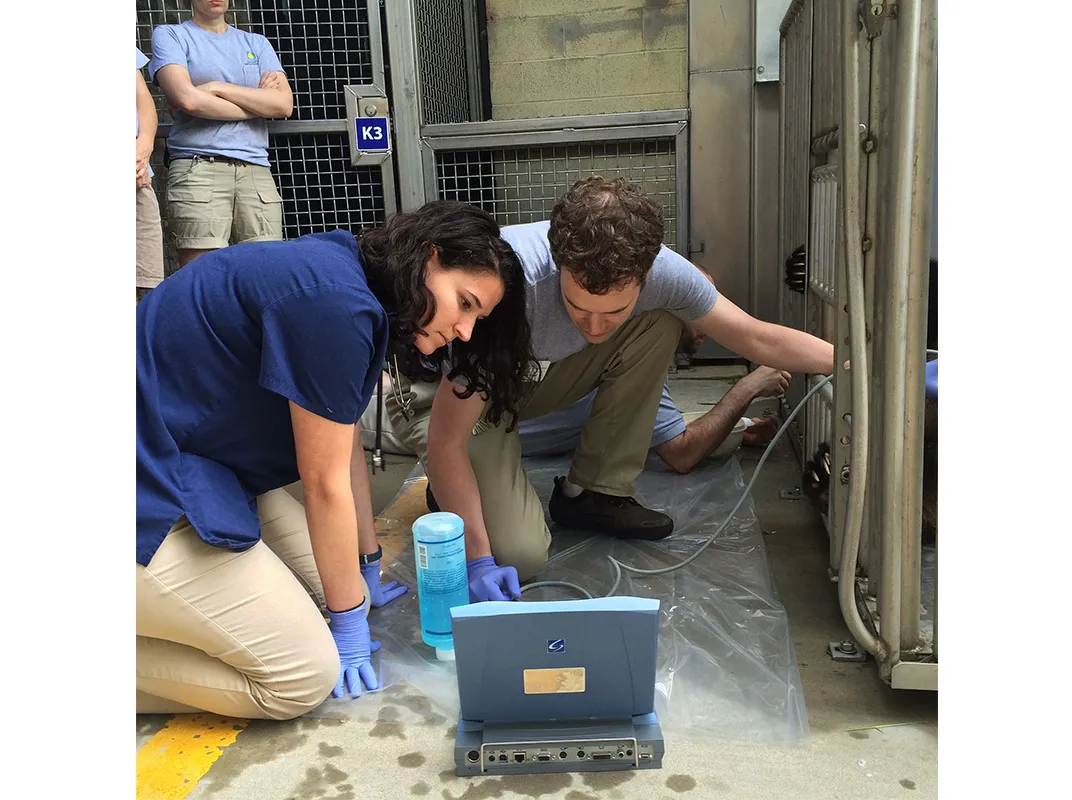

Panda keepers do use ultrasounds, but they’re far from foolproof. That's because in humans, the embryo plants itself in the uterine wall about 10 days after conception, where it begins growing into a human baby. In pandas, the fetus doesn’t implant into the uterus wall and begin developing until about three weeks before birth. So, “for most of the pregnancy, there’s no fetus to see,” Synder says. Until then, all you have is a tiny moving target: a cluster of free-floating cells somewhere in the uterus.

Researchers are currently examining proteins that circulate in the blood of the mother to find which ones could serve as pregnancy markers. At the San Diego Zoo, keepers have also used thermal imaging to measure increased blood flow to the stomach, another potential indicator. But there’s still a ways to go before we crack the panda’s reproductive code. “We’ve been exploring so many ways, and we haven’t really been able to find the secret,” says Comizzoli.

Can panda breeders really mistake poo for a panda embryo during an ultrasound?

This is a definite myth, says Snyder. But it’s true that fecal matter in the intestines can get in the way of ultrasound imaging. After all, giant pandas eat up to 36 pounds of bamboo a day. “It’s hard to image through all of that,” Synder says.

Do panda moms often crush their babies?

Panda cubs come out tiny and fragile, weighing less than 100 grams. That's compared to their mothers, who clock in at somewhere around 220 pounds. “This is a ratio rarely encountered in mammals,” says Comizzoli. Moreover, these delicate buttersticks are completely dependent on mom, who cradles them close to her bosom for weeks. “She’s almost like this big, furry incubator,” says Snyder. Given that size ratio and the amount of close contact between mom and baby, “there is some risk.”

To mitigate that risk, panda keepers watch over new moms with extreme vigilance, says Stephanie Braccini, curator of mammals at Zoo Atlanta. "We have round-the-clock observation and care for Lun Lun and her cubs for the first few months to ensure everyone is healthy and thriving," says Braccini. "It’s not uncommon for a giant panda mother to fall asleep and potentially roll over onto a cub, but with constant monitoring during those early months this can be avoided."

Snyder witnessed a few of these tense moments when she worked at Zoo Atlanta. But in pandas’ defense, “it doesn’t mean that the mom’s a bad mom,” she says. “It’s just that [she is] large compared to a very small, fragile infant. I have never witnessed a mother crush a cub, but it has happened in Chinese institutions.” Comizzoli adds that this kind of accident “is extremely rare,” and notes that death-by-sitting also occurs in other species, like cows.

Perhaps the real question we should be asking is: How do pandas accomplish the amazing feat of not crushing their babies? It turns out baby pandas have developed a fairly effective warning system to deter such parental behavior: Squeak for your life. A baby panda will regularly emit a piercing squeak for several days or weeks after birth, Comizzoli says, which helps his mother know his location and thus avoiding sitting on him.

Are pandas really the loving, affectionate creatures we make them out to be?

As much as we like to envision them nuzzling each other and caring for their babies, it simply isn’t so, says Comizzoli. “In the wild there is no commitment. They are not social animals, and do not live in couples. They are just solitary animals who meet during the breeding season, and that’s it,” he says, bursting all our bubbles. So there's really no such thing as panda love? “There is definitely attraction, for sure,” he says. “But then after that, where is the love and the commitment and really the passion? I’m not sure.”

While they may not be loving, at least they aren’t aggressive killers, so they've got that going for them. (Still, you should never try to hug a panda, as they can be quite dangerous when provoked, Comizzoli points out.) "For a bear species they really are more mellow, because they’ve gotten so herbivore-ified,” says Martin. “They eat a lot of bamboo, and it’s not a high energy source, so they’re not as active as the other bears.”

They've got another thing going for them, too: “They’re so easy to anthropomorphize," she says. "I even anthropomorphize them.”

Honestly, who could blame her?

The National Zoo is hosting “Bye Bye, Bao Bao” from February 11 through 20, featuring daily Facebook Live events and other happenings on the Panda Cam.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/HeadshotGross_Web.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/21/03/210310d4-c361-408f-9e5f-d3ae2998e336/8604872850_9c9ddbe2ef_k-wr.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/HeadshotGross_Web.jpg)