Our Imperiled Oceans: Seeing Is Believing

Photographs and other historical records testify to the former abundance of the sea

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/seeingisbelieving_sept08_631.jpg)

Whether it's a mess of bluegill hooked with a cane pole, a rare trout snagged with a fly or a sailfish suitable for mounting, people like to have their pictures taken with the fish they catch. They beam, proud and pleasantly sunburned, next to their prizes.

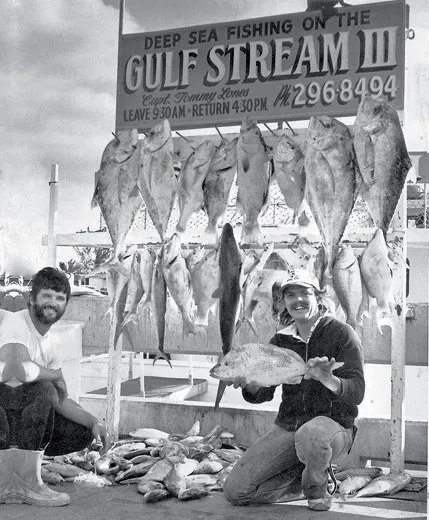

Loren McClenachan searches historical archives in the United States and Europe for such photos, and she found a trove of them in Key West, Florida, in the Monroe County Public Library. One set allowed her to look at fish caught by day-trippers aboard boats over the past 50 years. The first Gulf Stream fishing boat started operating out of Key West in 1947; today Gulf Stream III uses the same slip. Tourists' hairstyles and clothes change over the years, but the most striking difference is in the fish: they get smaller and fewer, and species disappear with the passage of time.

McClenachan, a graduate student at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography in San Diego, is part of a new field called historical marine ecology. Its scientists analyze old photographs, newspaper accounts, ships' logs and cannery records to estimate the quantity of fish that used to live in the sea. Some even look at old restaurant menus to learn when certain seafood became more costly, usually due to scarcity. McClenachan's study and others are part of the Census of Marine Life, a ten-year effort sponsored by foundations and governments worldwide that aims to understand the ocean's past and present, the better to predict the future.

The historical records reveal astonishing declines in most fish stocks. University of New Hampshire researchers, for instance, studied thousands of water-stained pages of 19th-century fishing port log books to determine that 150 years ago, there was 25 times as much cod off New England and Nova Scotia as today. Archaeologists in Europe have analyzed discarded fish bones going back 14 centuries. They conclude that milldams blocked salmon from swimming upstream in the 1100s; freshwater fish became scarcer over time; Europeans started eating more fish from the sea in the Middle Ages; and saltwater fish got smaller and smaller.

"Unfortunately, history has repeated itself again and again and again, to devastating effect," says Callum Roberts, a marine biologist at England's University of York. "People like food in big packages," he says, and they catch the biggest packages first, whether it's turtles or whales or cod or clams. And then they catch whatever is left—including animals so young that they haven't reproduced yet—until, in some cases, the food is gone. To break out of this spiral, Roberts says, "it is vital that we gain a clearer picture of what has been lost."

The basic remedy for a decline in fish—less fishing—has been clear since World War I, when a blockade of the North Sea shut down fishing for four years; afterward, catches doubled. In the past decade, marine reserves in the Caribbean, Hawaii and the Great Barrier Reef have allowed fish populations to increase not just in the protected areas but also in nearby waters, where fishing hauls are now more profitable.

In Key West, McClenachan analyzed photos from the three Gulf Streams and another boat, the Greyhound, as well as articles about trophy fish from the Key West Citizen newspaper. At scientific conferences earlier this year, she reported that she had identified and estimated the sizes of 1,275 fish from 100 photographs. In the 1950s, people caught huge grouper and sharks. In the 1970s, they landed a few grouper but more jack. Today's main catch is small snapper, which once weren't deemed worthy of a photo; people just piled them on the dock.

In the Keys, "the vast majority of commercially fished species, especially snapper and grouper, are badly overfished," says Brian Keller, NOAA's science coordinator for the Gulf of Mexico. Protection of endangered species and no-take zones in the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary have allowed some big fish, including the endangered goliath grouper, to begin a comeback. McClenachan's studies, he says, give fisheries managers "a better concept of what a restored ocean might look like."

The Gulf Stream and Greyhound, whose all-day outings cost about $50, including bait and tackle, cater to a wide variety of anglers, including McClenachan herself. "It was poignant," she says, to see so much excitement over catching fish. "The people on the boat don't have any sense that it's changed so much so quickly."

Laura Helmuth is a senior editor at Smithsonian.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/laura-helmuth-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/laura-helmuth-240.jpg)