A Paradise for Grizzly Bears Gets an Up-Close Look

This unique North American sanctuary lets a few lucky observers see the besieged species in its wildest state

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/4c/0d/4c0deb1e-5a0b-417b-8074-d1e9bc3e7eaf/nov2017_a04_grizzlies.jpg)

Our inflatable Zodiac boat snakes through a labyrinthine estuary off the coast of British Columbia. Mist hangs in the air. The glassy water mirrors the snowcapped mountains that jut 6,900 feet into the sky. Old-growth hemlock, Sitka spruce and cedar climb the craggy slopes, growing as thick and dense as the fur on a grizzly bear’s back.

“Hey bud, you’re all right,” Tom McPherson, our skipper and guide, says gently as we pull alongside a 300-pound bear with a fresh claw mark on one flank.

The blond bruin turns his back to us. He’s belly-deep in intertidal sedge—a protein-rich plant that coastal grizzlies devour for months after they emerge from their dens in April. He tears at the greens, swiping them with a heavy paw.

I’m with a handful of tourists and photographers near the Alaskan border in the Khutzeymateen Provincial Park, also known as the K’tzim-a-deen Grizzly Sanctuary. The refuge is jointly managed by BC Parks, the Tsimshian First Nations and the Gitsi’is Tribe, whose traditional territory encompasses the park. We flew in yesterday on a floatplane and landed on a glacial fjord. Our base camp: Ocean Light II, a 71-foot ketch-rigged sailboat operated by one of only a few outfitters licensed to enter the estuary in May and June.

Around 50 grizzlies live in the sanctuary. Right now, three of them are bounding through the marsh, water sloshing around their thick, brown fur. “They’re probably siblings,” McPherson says, and guesses they’re about 3 years old—the age at which mothers leave cubs to fend for themselves. Two of them play-fight, locking jaws and nipping each other’s necks—practice for the fierce combat that establishes adult hierarchies. After a few minutes, they resume grazing.

It takes a landscape to feed these far-ranging omnivores. In the sanctuary, they can roam freely across 170 square miles. In spring, they dig for skunk cabbage roots, their claws raking the soil and releasing nutrients that boost plant productivity. In summer, they feast on ripe berries and crab apples, scattering seeds in their scat, which prompts new growth. Early autumn brings the pre-hibernation pièce de résistance: salmon. The bears carry their catch to the shores, where the carcasses feed other mammals and birds and fertilize the trees.

“If you’re setting aside a large piece of wilderness that’s sufficient to house lots of grizzly bears,” says Rachel Forbes, executive director of Vancouver’s Grizzly Bear Foundation, “you’re also going to be supporting wolves, cougars, ungulates and everything that goes down from there, including the flora.” Indeed, the sanctuary teems with life. Harbor seals pop to the surface of the inlet, trailing us with their eyes. Eagles soar above the old-growth forest. Schools of smolt salmon flicker like quicksilver, preparing for their journey out to sea. Yesterday, we saw three Bigg’s orcas, and this morning, we played hide-and-seek with a juvenile humpback. The valley is home to mountain goats, minks, wolverines, wolves and other animals, including over 100 bird species.

Immersed in the grizzlies’ world, we watch their private dramas unfold. Swaggering dominant males tread shoreside paths; vigilant mothers sniff the air, followed by cubs. Two amorous bears scoot up a solid rock face and canoodle by a waterfall; a loner lies face-down on the beach, a pile of empty clamshells stacked beside him like crumpled beer cans.

On our first day, we saw 19 grizzlies, most of whom were used to human visitors and seemed indifferent to our presence. “We’re outnumbered!” someone joked, and everyone laughed. But elsewhere in North America, Homo sapiens greatly outnumber Ursus arctos horribilis—and we’re not nearly as accommodating as they are.

**********

Left to their own devices, grizzlies reproduce more slowly than many other forest animals, and cubs are sometimes eaten by adult males. While I was on the boat, rumors swirled about the notorious “Mr. P”—a massive, aggressive male who’d killed multiple cubs.

Still, it’s human activity that’s threatening them the most. In the 19th century, grizzlies roamed the western continental U.S., and as far south as Mexico, but conflicts with people have backed them into 2 percent of their original habitat.

While Alaska has a healthy grizzly population (more than 30,000), only 1,800 remain in the contiguous United States. In Canada, there are about 25,000, with about 15,000 of those in British Columbia; yet even in that province, 9 out of 56 population units are listed as “threatened.”

“The Khutzeymateen bears are among the most protected bears in the province today,” says Wayne McCrory, director of the Valhalla Wilderness Society, which battled the logging industry for years before the sanctuary was established in 1994. Elsewhere in the province, local and foreign hunters shoot an estimated 250 grizzlies annually. This summer, BC Premier John Horgan enacted a law that will ban all grizzly hunting in the Great Bear Rainforest. In the rest of the province, trophy hunting for hides, heads and paws will be forbidden, while hunting grizzlies for food will be permitted. It’s still unclear how the new law will be enforced.

Fortress of the Grizzlies: The Khutzeymateen Grizzly Bear Sanctuary

In a remote valley near the BC-Alaska border lives a remarkable group of grizzly bears who have never learned to fear humans. When logging threatened this valley, people from all over the world joined a battle to save the bears. In 1994, their efforts paid off with the establishment of the Khutzymateen Grizzly Bear Sanctuary, one of the world's most important protected wildlife areas.

South of the border, bears that wander beyond the boundaries of Yellowstone National Park in Idaho, Montana and Wyoming may soon be fair game. In 2016, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service issued a rule forbidding non-subsistence hunting of predators like bears and wolves in Alaska. This past March, Congress voted to overturn that rule.

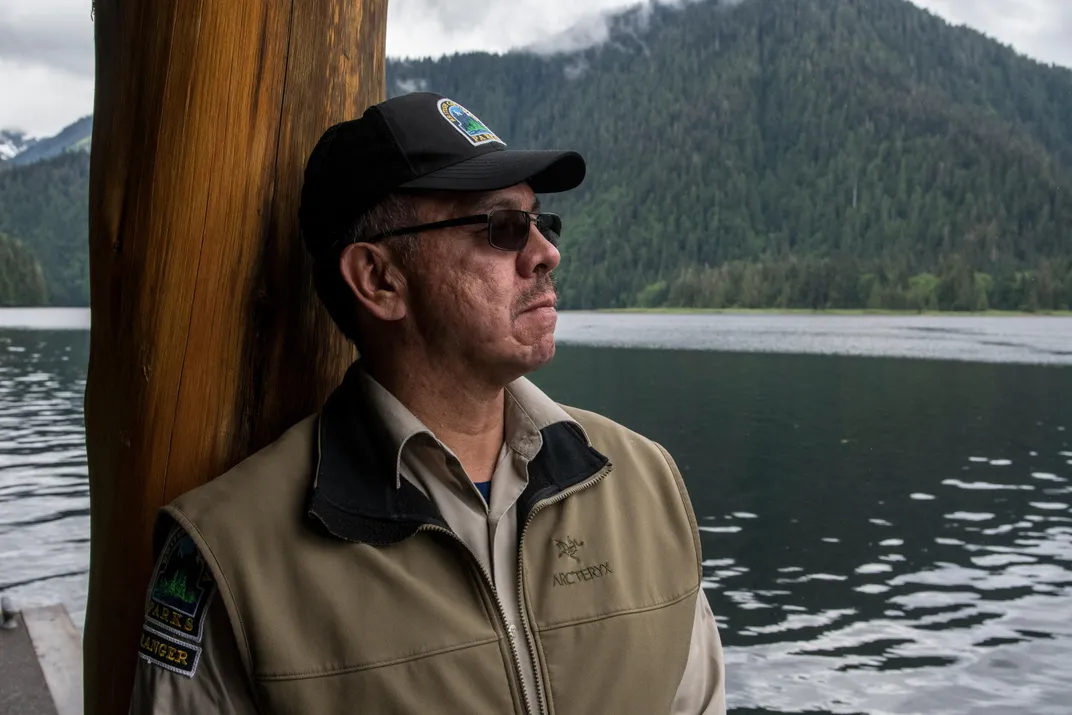

Norman Faithful, a guardian at the sanctuary and member of the Gitsi’is Tribe, says he would like more trophy hunters to come to the sanctuary and “see grizzlies in a different sense.” Although some First Nations people support trophy hunting, the Gitsi’is traditionally believed that when people die, their souls go into the grizzly bear for purification. “In the old days the grizzly bear was revered,” reads one of the educational posters adorning the ranger station’s wall, quoting the tribe’s late hereditary chief Laurence Helin. “You don’t kill the grizzly.”

**********

The three young grizzlies we saw earlier are now swimming from the estuary to the north shore of the inlet. Eventually, they clamber up on the rocks, where long wisps of old man’s beard sway from the limbs of hemlocks. Tuckered out from the swim, the largest of them leans against a fallen tree with heavy-lidded eyes, looking like a child who needs to be carried off to bed. He hauls himself over the log and hugs it like a body pillow, closing his eyes.

“Sound asleep,” whispers John E. Marriott, a wildlife photographer on our tour. “It’s like we don’t exist.”

Another bear beds down on a moss-covered rock that leans precariously over the water. “They don’t usually rest too long during the day,” McPherson says. Rain falls as we watch the bears sleep, their fur soaked through, their torsos rising and falling.

After some minutes, we zip off in our Zodiac and watch the young bears as they become small disappearing dots against the vast landscape.

*Editor's Note: An earlier version of this article said that grizzlies are fair game in Idaho, Montana and Wyoming. While there is no longer a federal ban on the practice in the areas surrounding Yellowstone National Park, the states themselves are still in the process of deciding whether to approve grizzly hunting.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.